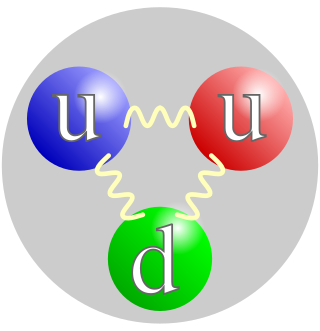

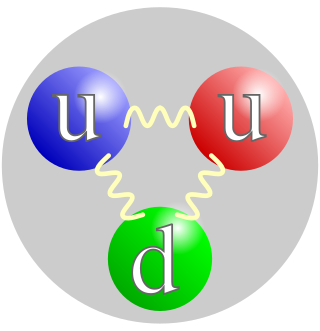

A gluon is a type of massless elementary particle that mediates the strong interaction between quarks, acting as the exchange particle for the interaction. Gluons are massless vector bosons, thereby having a spin of 1. Through the strong interaction, gluons bind quarks into groups according to quantum chromodynamics (QCD), forming hadrons such as protons and neutrons.

A quark is a type of elementary particle and a fundamental constituent of matter. Quarks combine to form composite particles called hadrons, the most stable of which are protons and neutrons, the components of atomic nuclei. All commonly observable matter is composed of up quarks, down quarks and electrons. Owing to a phenomenon known as color confinement, quarks are never found in isolation; they can be found only within hadrons, which include baryons and mesons, or in quark–gluon plasmas. For this reason, much of what is known about quarks has been drawn from observations of hadrons.

In theoretical physics, quantum chromodynamics (QCD) is the study of the strong interaction between quarks mediated by gluons. Quarks are fundamental particles that make up composite hadrons such as the proton, neutron and pion. QCD is a type of quantum field theory called a non-abelian gauge theory, with symmetry group SU(3). The QCD analog of electric charge is a property called color. Gluons are the force carriers of the theory, just as photons are for the electromagnetic force in quantum electrodynamics. The theory is an important part of the Standard Model of particle physics. A large body of experimental evidence for QCD has been gathered over the years.

The strange quark or s quark is the third lightest of all quarks, a type of elementary particle. Strange quarks are found in subatomic particles called hadrons. Examples of hadrons containing strange quarks include kaons, strange D mesons, Sigma baryons, and other strange particles.

The omega baryons are a family of subatomic hadron particles that are represented by the symbol

Ω

and are either neutral or have a +2, +1 or −1 elementary charge. They are baryons containing no up or down quarks. Omega baryons containing top quarks are not expected to be observed. This is because the Standard Model predicts the mean lifetime of top quarks to be roughly 5×10−25 s, which is about a twentieth of the timescale for strong interactions, and therefore that they do not form hadrons.

The up quark or u quark is the lightest of all quarks, a type of elementary particle, and a significant constituent of matter. It, along with the down quark, forms the neutrons and protons of atomic nuclei. It is part of the first generation of matter, has an electric charge of +2/3 e and a bare mass of 2.2+0.5

−0.4 MeV/c2. Like all quarks, the up quark is an elementary fermion with spin 1/2, and experiences all four fundamental interactions: gravitation, electromagnetism, weak interactions, and strong interactions. The antiparticle of the up quark is the up antiquark, which differs from it only in that some of its properties, such as charge have equal magnitude but opposite sign.

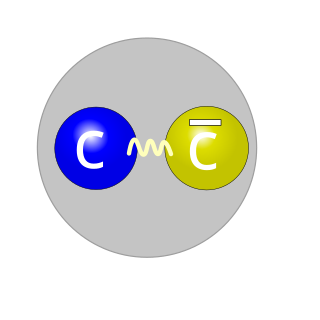

The charm quark, charmed quark, or c quark is an elementary particle found in composite subatomic particles called hadrons such as the J/psi meson and the charmed baryons created in particle accelerator collisions. Several bosons, including the W and Z bosons and the Higgs boson, can decay into charm quarks. All charm quarks carry charm, a quantum number. This second generation particle is the third-most-massive quark with a mass of 1.27±0.02 GeV/c2 as measured in 2022 and a charge of +2/3 e.

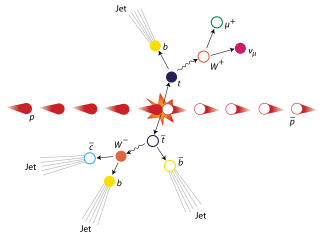

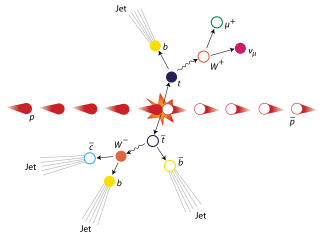

The top quark, sometimes also referred to as the truth quark, is the most massive of all observed elementary particles. It derives its mass from its coupling to the Higgs Boson. This coupling is very close to unity; in the Standard Model of particle physics, it is the largest (strongest) coupling at the scale of the weak interactions and above. The top quark was discovered in 1995 by the CDF and DØ experiments at Fermilab.

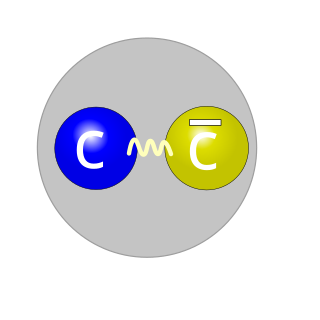

The

J/ψ

(J/psi) meson is a subatomic particle, a flavor-neutral meson consisting of a charm quark and a charm antiquark. Mesons formed by a bound state of a charm quark and a charm anti-quark are generally known as "charmonium" or psions. The

J/ψ

is the most common form of charmonium, due to its spin of 1 and its low rest mass. The

J/ψ

has a rest mass of 3.0969 GeV/c2, just above that of the

η

c, and a mean lifetime of 7.2×10−21 s. This lifetime was about a thousand times longer than expected.

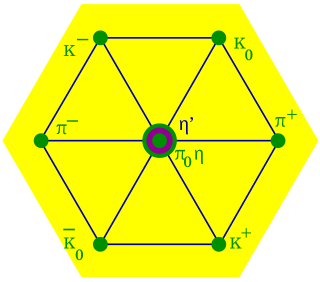

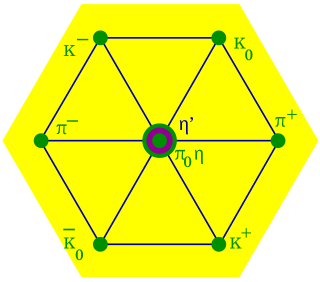

In physics, the eightfold way is an organizational scheme for a class of subatomic particles known as hadrons that led to the development of the quark model. Working alone, both the American physicist Murray Gell-Mann and the Israeli physicist Yuval Ne'eman proposed the idea in 1961. The name comes from Gell-Mann's (1961) paper and is an allusion to the Noble Eightfold Path of Buddhism.

In high-energy physics, a pseudoscalar meson is a meson with total spin 0 and odd parity . Pseudoscalar mesons are commonly seen in proton-proton scattering and proton-antiproton annihilation, and include the pion, kaon, eta, and eta prime particles, whose masses are known with great precision.

In particle physics, flavour or flavor refers to the species of an elementary particle. The Standard Model counts six flavours of quarks and six flavours of leptons. They are conventionally parameterized with flavour quantum numbers that are assigned to all subatomic particles. They can also be described by some of the family symmetries proposed for the quark-lepton generations.

Exotic hadrons are subatomic particles composed of quarks and gluons, but which – unlike "well-known" hadrons such as protons, neutrons and mesons – consist of more than three valence quarks. By contrast, "ordinary" hadrons contain just two or three quarks. Hadrons with explicit valence gluon content would also be considered exotic. In theory, there is no limit on the number of quarks in a hadron, as long as the hadron's color charge is white, or color-neutral.

In particle physics, the quark model is a classification scheme for hadrons in terms of their valence quarks—the quarks and antiquarks that give rise to the quantum numbers of the hadrons. The quark model underlies "flavor SU(3)", or the Eightfold Way, the successful classification scheme organizing the large number of lighter hadrons that were being discovered starting in the 1950s and continuing through the 1960s. It received experimental verification beginning in the late 1960s and is a valid and effective classification of them to date. The model was independently proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann, who dubbed them "quarks" in a concise paper, and George Zweig, who suggested "aces" in a longer manuscript. André Petermann also touched upon the central ideas from 1963 to 1965, without as much quantitative substantiation. Today, the model has essentially been absorbed as a component of the established quantum field theory of strong and electroweak particle interactions, dubbed the Standard Model.

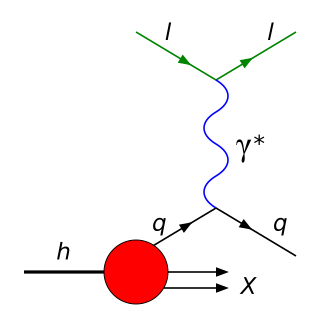

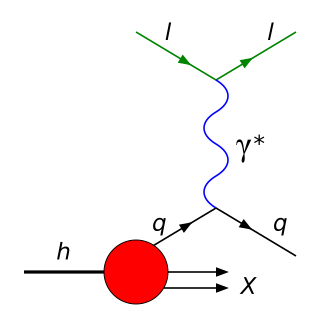

In particle physics, deep inelastic scattering is the name given to a process used to probe the insides of hadrons, using electrons, muons and neutrinos. It was first attempted in the 1960s and 1970s and provided the first convincing evidence of the reality of quarks, which up until that point had been considered by many to be a purely mathematical phenomenon. It is an extension of Rutherford scattering to much higher energies of the scattering particle and thus to much finer resolution of the components of the nuclei.

In particle physics, the parton model is a model of hadrons, such as protons and neutrons, proposed by Richard Feynman. It is useful for interpreting the cascades of radiation produced from quantum chromodynamics (QCD) processes and interactions in high-energy particle collisions.

In particle physics, chiral symmetry breaking generally refers to the dynamical spontaneous breaking of a chiral symmetry associated with massless fermions. This is usually associated with a gauge theory such as quantum chromodynamics, the quantum field theory of the strong interaction, and it also occurs through the Brout-Englert-Higgs mechanism in the electroweak interactions of the standard model. This phenomenon is analogous to magnetization and superconductivity in condensed matter physics. The basic idea was introduced to particle physics by Yoichiro Nambu, in particular, in the Nambu–Jona-Lasinio model, which is a solvable theory of composite bosons that exhibits dynamical spontaneous chiral symmetry when a 4-fermion coupling constant becomes sufficiently large. Nambu was awarded the 2008 Nobel prize in physics "for the discovery of the mechanism of spontaneous broken symmetry in subatomic physics".

The timeline of particle physics lists the sequence of particle physics theories and discoveries in chronological order. The most modern developments follow the scientific development of the discipline of particle physics.

In physics, the Gell-Mann–Okubo mass formula provides a sum rule for the masses of hadrons within a specific multiplet, determined by their isospin (I) and strangeness (or alternatively, hypercharge)

In strong interaction physics, light front holography or light front holographic QCD is an approximate version of the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD) which results from mapping the gauge theory of QCD to a higher-dimensional anti-de Sitter space (AdS) inspired by the AdS/CFT correspondence proposed for string theory. This procedure makes it possible to find analytic solutions in situations where strong coupling occurs, improving predictions of the masses of hadrons and their internal structure revealed by high-energy accelerator experiments. The most widely used approach to finding approximate solutions to the QCD equations, lattice QCD, has had many successful applications; however, it is a numerical approach formulated in Euclidean space rather than physical Minkowski space-time.