The United States Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), also called the FISA Court, is a U.S. federal court established under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act of 1978 (FISA) to oversee requests for surveillance warrants against foreign spies inside the United States by federal law enforcement and intelligence agencies.

The following are controversial invocations of the USA PATRIOT Act. The stated purpose of the Act is to "deter and punish terrorist acts in the United States and around the world, to enhance law enforcement investigatory tools, and for other purposes." One criticism of the Act is that "other purposes" often includes the detection and prosecution of non-terrorist alleged future crimes.

American Civil Liberties Union v. National Security Agency, 493 F.3d 644, is a case decided July 6, 2007, in which the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit held that the plaintiffs in the case did not have standing to bring the suit against the National Security Agency (NSA), because they could not present evidence that they were the targets of the so-called "Terrorist Surveillance Program" (TSP).

Hepting v. AT&T, 439 F.Supp.2d 974, was a class action lawsuit argued before the United States District Court for the Northern District of California, filed by Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) on behalf of customers of the telecommunications company AT&T. The plaintiffs alleged that AT&T permitted and assisted the National Security Agency (NSA) in unlawfully monitoring the personal communications of American citizens, including AT&T customers, whose communications were routed through AT&T's network.

MAINWAY is a database maintained by the United States' National Security Agency (NSA) containing metadata for hundreds of billions of telephone calls made through the largest telephone carriers in the United States, including AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile.

Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979), was a Supreme Court case holding that the installation and use of a pen register by the police to obtain information on a suspect's telephone calls was not a "search" within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, and hence no search warrant was required. In the majority opinion, Justice Harry Blackmun rejected the idea that the installation and use of a pen register constitutes a violation of the suspect's reasonable expectation of privacy since the telephone numbers would be available to and recorded by the phone company anyway.

Jewel v. National Security Agency, 673 F.3d 902, was a class action lawsuit argued before the District Court for the Northern District of California and the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, filed by Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) on behalf of American citizens who believed that they had been surveilled by the National Security Agency (NSA) without a warrant. The EFF alleged that the NSA's surveillance program was an "illegal and unconstitutional program of dragnet communications surveillance" and claimed violations of the Fourth Amendment.

PRISM is a code name for a program under which the United States National Security Agency (NSA) collects internet communications from various U.S. internet companies. The program is also known by the SIGAD US-984XN. PRISM collects stored internet communications based on demands made to internet companies such as Google LLC and Apple under Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act of 2008 to turn over any data that match court-approved search terms. Among other things, the NSA can use these PRISM requests to target communications that were encrypted when they traveled across the internet backbone, to focus on stored data that telecommunication filtering systems discarded earlier, and to get data that is easier to handle.

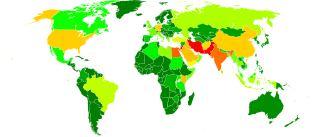

The practice of mass surveillance in the United States dates back to wartime monitoring and censorship of international communications from, to, or which passed through the United States. After the First and Second World Wars, mass surveillance continued throughout the Cold War period, via programs such as the Black Chamber and Project SHAMROCK. The formation and growth of federal law-enforcement and intelligence agencies such as the FBI, CIA, and NSA institutionalized surveillance used to also silence political dissent, as evidenced by COINTELPRO projects which targeted various organizations and individuals. During the Civil Rights Movement era, many individuals put under surveillance orders were first labelled as integrationists, then deemed subversive, and sometimes suspected to be supportive of the communist model of the United States' rival at the time, the Soviet Union. Other targeted individuals and groups included Native American activists, African American and Chicano liberation movement activists, and anti-war protesters.

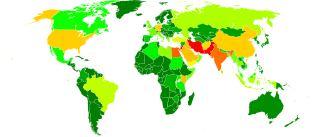

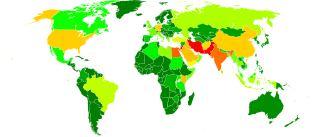

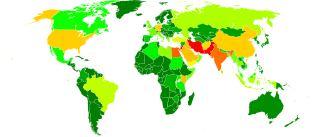

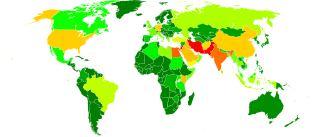

Ongoing news reports in the international media have revealed operational details about the Anglophone cryptographic agencies' global surveillance of both foreign and domestic nationals. The reports mostly emanate from a cache of top secret documents leaked by ex-NSA contractor Edward Snowden, which he obtained whilst working for Booz Allen Hamilton, one of the largest contractors for defense and intelligence in the United States. In addition to a trove of U.S. federal documents, Snowden's cache reportedly contains thousands of Australian, British, Canadian and New Zealand intelligence files that he had accessed via the exclusive "Five Eyes" network. In June 2013, the first of Snowden's documents were published simultaneously by The Washington Post and The Guardian, attracting considerable public attention. The disclosure continued throughout 2013, and a small portion of the estimated full cache of documents was later published by other media outlets worldwide, most notably The New York Times, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Der Spiegel (Germany), O Globo (Brazil), Le Monde (France), L'espresso (Italy), NRC Handelsblad, Dagbladet (Norway), El País (Spain), and Sveriges Television (Sweden).

The global surveillance disclosure released to media by Edward Snowden has caused tension in the bilateral relations of the United States with several of its allies and economic partners as well as in its relationship with the European Union. In August 2013, U.S. President Barack Obama announced the creation of "a review group on intelligence and communications technologies" that would brief and later report to him. In December, the task force issued 46 recommendations that, if adopted, would subject the National Security Agency (NSA) to additional scrutiny by the courts, Congress, and the president, and would strip the NSA of the authority to infiltrate American computer systems using "backdoors" in hardware or software. Geoffrey R. Stone, a White House panel member, said there was no evidence that the bulk collection of phone data had stopped any terror attacks.

This is a category of disclosures related to global surveillance.

The Fourth Amendment Protection Acts, are a collection of state legislation aimed at withdrawing state support for bulk data (metadata) collection and ban the use of warrant-less data in state courts. They are proposed nullification laws that, if enacted as law, would prohibit the state governments from co-operating with the National Security Agency, whose mass surveillance efforts are seen as unconstitutional by the proposals' proponents. Specific examples include the Kansas Fourth Amendment Preservation and Protection Act and the Arizona Fourth Amendment Protection Act. The original proposals were made in 2013 and 2014 by legislators in the American states of Utah, Washington, Arizona, Kansas, Missouri, Oklahoma and California. Some of the bills would require a warrant before information could be released, whereas others would forbid state universities from doing NSA research or hosting NSA recruiters, or prevent the provision of services such as water to NSA facilities.

Proposed reforms of mass surveillance by the United States are a collection of diverse proposals offered in response to the Global surveillance disclosures of 2013.

Former U.S. President Barack Obama favored some levels of mass surveillance. He has received some widespread criticism from detractors as a result. Due to his support of certain government surveillance, some critics have said his support may have gone beyond acceptable privacy rights. This is of course a debatable conclusion. Many former US presidents have increased the abilities and techniques used for intelligence gathering. President Obama released many statements on mass surveillance.

American Civil Liberties Union v. Clapper, 785 F.3d 787, was a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and its affiliate, the New York Civil Liberties Union, against the United States federal government as represented by then-Director of National Intelligence James Clapper. The ACLU challenged the legality and constitutionality of the National Security Agency's (NSA) bulk phone metadata collection program.

Litigation over global surveillance has occurred in multiple jurisdictions since the global surveillance disclosures of 2013.

In Re Electronic Privacy Information Center, 134 S.Ct. 638 (2013), was a direct petition to the Supreme Court of the United States regarding the National Security Agency's (NSA) telephony metadata collection program. On July 8, 2013, the Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) filed a petition for a writ of mandamus and prohibition, or a writ of certiorari, to vacate an order of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) in which the court compelled Verizon to produce telephony metadata records from all of its subscribers' calls and deliver those records to the NSA. On November 18, 2013, the Supreme Court denied EPIC's petition.

This timeline of global surveillance disclosures from 2013 to the present day is a chronological list of the global surveillance disclosures that began in 2013. The disclosures have been largely instigated by revelations from the former American National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden.

Wikimedia Foundation, et al. v. National Security Agency, et al. is a lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) on behalf of the Wikimedia Foundation and several other organizations against the National Security Agency (NSA), the United States Department of Justice (DOJ), and other named individuals, alleging mass surveillance of Wikipedia users carried out by the NSA. The suit claims the surveillance system, which NSA calls "Upstream", breaches the First Amendment to the United States Constitution, which protects freedom of speech, and the Fourth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures.