A high-pass filter (HPF) is an electronic filter that passes signals with a frequency higher than a certain cutoff frequency and attenuates signals with frequencies lower than the cutoff frequency. The amount of attenuation for each frequency depends on the filter design. A high-pass filter is usually modeled as a linear time-invariant system. It is sometimes called a low-cut filter or bass-cut filter in the context of audio engineering. High-pass filters have many uses, such as blocking DC from circuitry sensitive to non-zero average voltages or radio frequency devices. They can also be used in conjunction with a low-pass filter to produce a band-pass filter.

Capacitance is the capability of a material object or device to store electric charge. It is measured by the charge in response to a difference in electric potential, expressed as the ratio of those quantities. Commonly recognized are two closely related notions of capacitance: self capacitance and mutual capacitance. An object that can be electrically charged exhibits self capacitance, for which the electric potential is measured between the object and ground. Mutual capacitance is measured between two components, and is particularly important in the operation of the capacitor, an elementary linear electronic component designed to add capacitance to an electric circuit.

A resistor–capacitor circuit, or RC filter or RC network, is an electric circuit composed of resistors and capacitors. It may be driven by a voltage or current source and these will produce different responses. A first order RC circuit is composed of one resistor and one capacitor and is the simplest type of RC circuit.

In electronics, a voltage divider (also known as a potential divider) is a passive linear circuit that produces an output voltage (Vout) that is a fraction of its input voltage (Vin). Voltage division is the result of distributing the input voltage among the components of the divider. A simple example of a voltage divider is two resistors connected in series, with the input voltage applied across the resistor pair and the output voltage emerging from the connection between them.

A gyrator is a passive, linear, lossless, two-port electrical network element proposed in 1948 by Bernard D. H. Tellegen as a hypothetical fifth linear element after the resistor, capacitor, inductor and ideal transformer. Unlike the four conventional elements, the gyrator is non-reciprocal. Gyrators permit network realizations of two-(or-more)-port devices which cannot be realized with just the four conventional elements. In particular, gyrators make possible network realizations of isolators and circulators. Gyrators do not however change the range of one-port devices that can be realized. Although the gyrator was conceived as a fifth linear element, its adoption makes both the ideal transformer and either the capacitor or inductor redundant. Thus the number of necessary linear elements is in fact reduced to three. Circuits that function as gyrators can be built with transistors and op-amps using feedback.

In electronics, a common-emitter amplifier is one of three basic single-stage bipolar-junction-transistor (BJT) amplifier topologies, typically used as a voltage amplifier. It offers high current gain, medium input resistance and a high output resistance. The output of a common emitter amplifier is inverted; i.e. for a sine wave input signal, the output signal is 180 degrees out of phase with respect to the input.

A Colpitts oscillator, invented in 1918 by Canadian-American engineer Edwin H. Colpitts using vacuum tubes, is one of a number of designs for LC oscillators, electronic oscillators that use a combination of inductors (L) and capacitors (C) to produce an oscillation at a certain frequency. The distinguishing feature of the Colpitts oscillator is that the feedback for the active device is taken from a voltage divider made of two capacitors in series across the inductor.

In electronics, a common-source amplifier is one of three basic single-stage field-effect transistor (FET) amplifier topologies, typically used as a voltage or transconductance amplifier. The easiest way to tell if a FET is common source, common drain, or common gate is to examine where the signal enters and leaves. The remaining terminal is what is known as "common". In this example, the signal enters the gate, and exits the drain. The only terminal remaining is the source. This is a common-source FET circuit. The analogous bipolar junction transistor circuit may be viewed as a transconductance amplifier or as a voltage amplifier.. As a transconductance amplifier, the input voltage is seen as modulating the current going to the load. As a voltage amplifier, input voltage modulates the current flowing through the FET, changing the voltage across the output resistance according to Ohm's law. However, the FET device's output resistance typically is not high enough for a reasonable transconductance amplifier, nor low enough for a decent voltage amplifier. As seen below in the formula, the voltage gain depends on the load resistance, so it cannot be applied to drive low-resistance devices, such as a speaker. Another major drawback is the amplifier's limited high-frequency response. Therefore, in practice the output often is routed through either a voltage follower, or a current follower, to obtain more favorable output and frequency characteristics. The CS–CG combination is called a cascode amplifier.

The cascode is a two-stage amplifier that consists of a common-emitter stage feeding into a common-base stage.

This article illustrates some typical operational amplifier applications. A non-ideal operational amplifier's equivalent circuit has a finite input impedance, a non-zero output impedance, and a finite gain. A real op-amp has a number of non-ideal features as shown in the diagram, but here a simplified schematic notation is used, many details such as device selection and power supply connections are not shown. Operational amplifiers are optimised for use with negative feedback, and this article discusses only negative-feedback applications. When positive feedback is required, a comparator is usually more appropriate. See Comparator applications for further information.

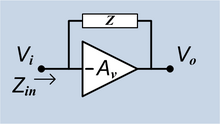

In electronics, the Miller effect accounts for the increase in the equivalent input capacitance of an inverting voltage amplifier due to amplification of the effect of capacitance between the amplifier's input and output terminals, and is given by

A buck converter or step-down converter is a DC-to-DC converter which decreases voltage, while increasing current, from its input (supply) to its output (load). It is a class of switched-mode power supply. Switching converters provide much greater power efficiency as DC-to-DC converters than linear regulators, which are simpler circuits that dissipate power as heat, but do not step up output current. The efficiency of buck converters can be very high, often over 90%, making them useful for tasks such as converting a computer's main supply voltage, which is usually 12 V, down to lower voltages needed by USB, DRAM and the CPU, which are usually 5, 3.3 or 1.8 V.

A charge amplifier is an electronic current integrator that produces a voltage output proportional to the integrated value of the input current, or the total charge injected.

Ripple in electronics is the residual periodic variation of the DC voltage within a power supply which has been derived from an alternating current (AC) source. This ripple is due to incomplete suppression of the alternating waveform after rectification. Ripple voltage originates as the output of a rectifier or from generation and commutation of DC power.

In electronics, a decoupling capacitor is a capacitor used to decouple one part of a circuit from another. Noise caused by other circuit elements is shunted through the capacitor, reducing its effect on the rest of the circuit. For higher frequencies, an alternative name is bypass capacitor as it is used to bypass the power supply or other high-impedance component of a circuit.

In electrical engineering, a capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy by accumulating electric charges on two closely spaced surfaces that are insulated from each other. The capacitor was originally known as the condenser, a term still encountered in a few compound names, such as the condenser microphone. It is a passive electronic component with two terminals.

A switched capacitor (SC) is an electronic circuit that implements a function by moving charges into and out of capacitors when electronic switches are opened and closed. Usually, non-overlapping clock signals are used to control the switches, so that not all switches are closed simultaneously. Filters implemented with these elements are termed switched-capacitor filters, which depend only on the ratios between capacitances and the switching frequency, and not on precise resistors. This makes them much more suitable for use within integrated circuits, where accurately specified resistors and capacitors are not economical to construct, but accurate clocks and accurate relative ratios of capacitances are economical.

In electronics, a differentiator is a circuit designed to produce an output approximately proportional to the rate of change of the input. A true differentiator cannot be physically realized, because it has infinite gain at infinite frequency. A similar effect can be achieved, however, by limiting the gain above some frequency. The differentiator circuit is essentially a high-pass filter. An active differentiator includes some form of amplifier, while a passive differentiator is made only of resistors, capacitors and inductors.

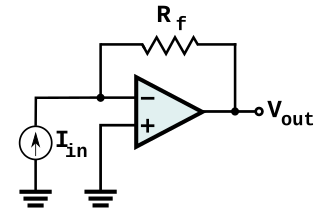

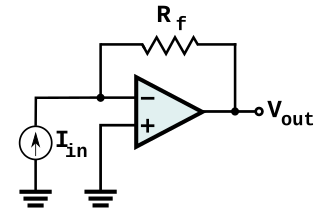

In electronics, a transimpedance amplifier (TIA) is a current to voltage converter, almost exclusively implemented with one or more operational amplifiers. The TIA can be used to amplify the current output of Geiger–Müller tubes, photo multiplier tubes, accelerometers, photo detectors and other types of sensors to a usable voltage. Current to voltage converters are used with sensors that have a current response that is more linear than the voltage response. This is the case with photodiodes where it is not uncommon for the current response to have better than 1% nonlinearity over a wide range of light input. The transimpedance amplifier presents a low impedance to the photodiode and isolates it from the output voltage of the operational amplifier. In its simplest form a transimpedance amplifier has just a large valued feedback resistor, Rf. The gain of the amplifier is set by this resistor and because the amplifier is in an inverting configuration, has a value of -Rf. There are several different configurations of transimpedance amplifiers, each suited to a particular application. The one factor they all have in common is the requirement to convert the low-level current of a sensor to a voltage. The gain, bandwidth, as well as current and voltage offsets change with different types of sensors, requiring different configurations of transimpedance amplifiers.

The operational amplifier integrator is an electronic integration circuit. Based on the operational amplifier (op-amp), it performs the mathematical operation of integration with respect to time; that is, its output voltage is proportional to the input voltage integrated over time.