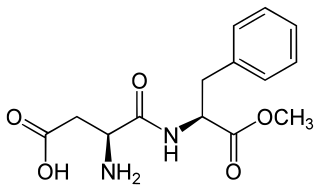

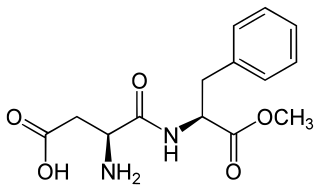

Aspartame is an artificial non-saccharide sweetener 200 times sweeter than sucrose and is commonly used as a sugar substitute in foods and beverages. It is a methyl ester of the aspartic acid/phenylalanine dipeptide with brand names NutraSweet, Equal, and Canderel. Aspartame was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1974, and then again in 1981, after approval was revoked in 1980.

The Brassicales are an order of flowering plants, belonging to the eurosids II group of dicotyledons under the APG II system. One character common to many members of the order is the production of glucosinolate compounds. Most systems of classification have included this order, although sometimes under the name Capparales.

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or fungal origin and contains essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, proteins, vitamins, or minerals. The substance is ingested by an organism and assimilated by the organism's cells to provide energy, maintain life, or stimulate growth. Different species of animals have different feeding behaviours that satisfy the needs of their metabolisms and have evolved to fill a specific ecological niche within specific geographical contexts.

Stevia is a sweet sugar substitute that is about 50 to 300 times sweeter than sugar. It is extracted from the leaves of Stevia rebaudiana, a plant native to areas of Paraguay and Brazil in the southern Amazon rainforest. The active compounds in stevia are steviol glycosides. Stevia is heat-stable, pH-stable, and not fermentable. Humans cannot metabolize the glycosides in stevia, and therefore it has zero calories. Its taste has a slower onset and longer duration than that of sugar, and at high concentrations some of its extracts may have an aftertaste described as licorice-like or bitter. Stevia is used in sugar- and calorie-reduced food and beverage products as an alternative for variants with sugar.

Broccoli is an edible green plant in the cabbage family whose large flowering head, stalk and small associated leaves are eaten as a vegetable. Broccoli is classified in the Italica cultivar group of the species Brassica oleracea. Broccoli has large flower heads, or florets, usually dark green, arranged in a tree-like structure branching out from a thick stalk which is usually light green. The mass of flower heads is surrounded by leaves. Broccoli resembles cauliflower, which is a different but closely related cultivar group of the same Brassica species.

Thaumatin is a low-calorie sweetener and flavor modifier. The protein is often used primarily for its flavor-modifying properties and not exclusively as a sweetener.

Neohesperidin dihydrochalcone, sometimes abbreviated to neohesperidin DC or simply NHDC, is an artificial sweetener derived from citrus.

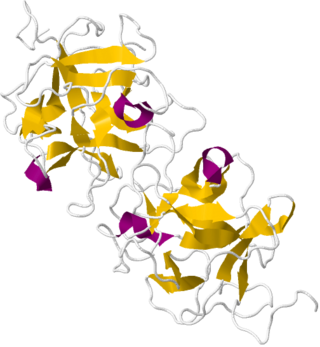

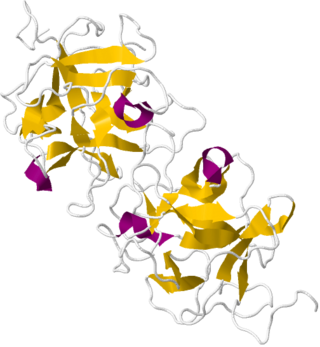

Monellin, a sweet protein, was discovered in 1969 in the fruit of the West African shrub known as serendipity berry ; it was first reported as a carbohydrate. The protein was named in 1972 after the Monell Chemical Senses Center in Philadelphia, U.S.A., where it was isolated and characterized.

Miraculin is a taste modifier, a glycoprotein extracted from the fruit of Synsepalum dulcificum. The berry, also known as the miracle fruit, was documented by explorer Chevalier des Marchais, who searched for many different fruits during a 1725 excursion to its native West Africa.

Sweetness is a basic taste most commonly perceived when eating foods rich in sugars. Sweet tastes are generally regarded as pleasurable. In addition to sugars like sucrose, many other chemical compounds are sweet, including aldehydes, ketones, and sugar alcohols. Some are sweet at very low concentrations, allowing their use as non-caloric sugar substitutes. Such non-sugar sweeteners include saccharin, aspartame, sucralose and stevia. Other compounds, such as miraculin, may alter perception of sweetness itself.

Synsepalum dulcificum is a plant in the Sapotaceae family, native to tropical Africa. It is known for its berry that, when eaten, causes sour foods subsequently consumed to taste sweet. This effect is due to miraculin. Common names for this species and its berry include miracle fruit, miracle berry, miraculous berry, sweet berry, and in West Africa, where the species originates, agbayun, taami, asaa, and ledidi.

Brazzein is a protein found in the West African fruit of Oubli. It was first isolated by the University of Wisconsin–Madison in 1994.

Sabiaceae is a family of flowering plants that were placed in the order Proteales according to the APG IV system. It comprises three genera, Meliosma, Ophiocaryon and Sabia, with 66 known species, native to tropical to warm temperate regions of southern Asia and the Americas. The family has also been called Meliosmaceae Endl., 1841, nom. rej.

The Cleomaceae are a small family of flowering plants in the order Brassicales, comprising about 220 species in two genera, Cleome and Cleomella. These genera were previously included in the family Capparaceae, but were raised to a distinct family when DNA evidence suggested the genera included in it are more closely related to the Brassicaceae than they are to the Capparaceae. The APG II system allows for Cleomaceae to be included in Brassicaceae. Cleomaceae includes C3, C3–C4, and C4 photosynthesis species.

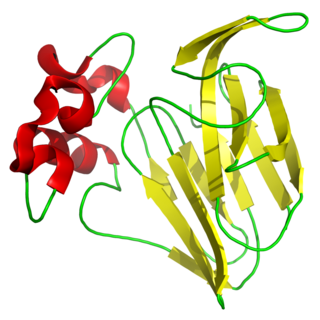

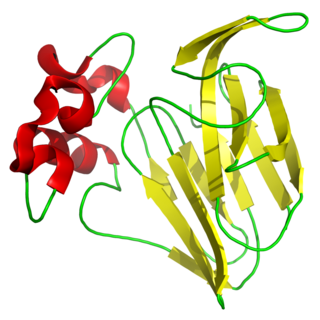

Curculin or neoculin is a sweet protein that was discovered and isolated in 1990 from the fruit of Curculigo latifolia (Hypoxidaceae), a plant from Malaysia. Like miraculin, curculin exhibits taste-modifying activity; however, unlike miraculin, it also exhibits a sweet taste by itself. After consumption of curculin, water and sour solutions taste sweet. The plant is referred to locally as 'Lumbah' or 'Lemba'.

Pentadin, a sweet-tasting protein, was discovered and isolated in 1989, in the fruit of oubli, a climbing shrub growing in some tropical countries of Africa. Sweet tasting proteins are often used in the treatment of diabetes, obesity, and other metabolic disorders that one can experience. These proteins are isolated from the pulp of various fruits, typically found in rain forests and are also used as low calorie sweeteners that can enhance and modify existing foods.

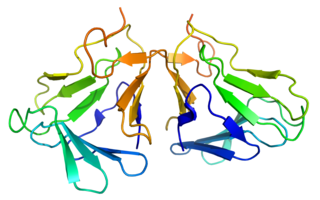

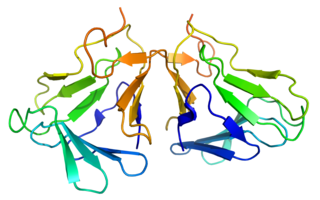

Taste receptor type 1 member 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TAS1R1 gene.

T1R2 - Taste receptor type 1 member 2 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TAS1R2 gene.

Taste receptor type 1 member 3 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TAS1R3 gene. The TAS1R3 gene encodes the human homolog of mouse Sac taste receptor, a major determinant of differences between sweet-sensitive and -insensitive mouse strains in their responsiveness to sucrose, saccharin, and other sweeteners.

Thaumatococcus daniellii, also known as miracle fruit or miracle berry, is a plant species from tropical Africa of the Marantaceae family. It is a large, rhizomatous, flowering herb native to the rainforests of western Africa in Sierra Leone, southeast to Gabon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is also an introduced species in Australia and Singapore.