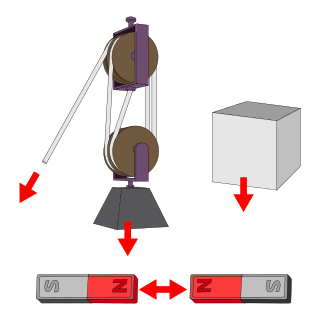

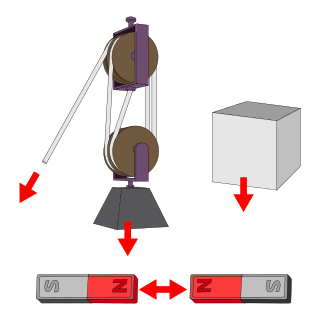

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an object to change its velocity, i.e., to accelerate, meaning a change in speed or direction, unless counterbalanced by other forces. The concept of force makes the everyday notion of pushing or pulling mathematically precise. Because the magnitude and direction of a force are both important, force is a vector quantity. The SI unit of force is the newton (N), and force is often represented by the symbol F.

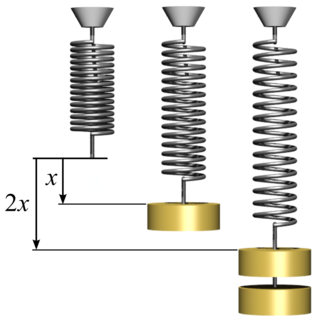

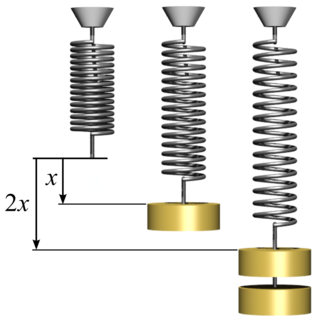

In classical mechanics, a harmonic oscillator is a system that, when displaced from its equilibrium position, experiences a restoring force F proportional to the displacement x:

Oscillation is the repetitive or periodic variation, typically in time, of some measure about a central value or between two or more different states. Familiar examples of oscillation include a swinging pendulum and alternating current. Oscillations can be used in physics to approximate complex interactions, such as those between atoms.

In physics, potential energy is the energy held by an object because of its position relative to other objects, stresses within itself, its electric charge, or other factors. The term potential energy was introduced by the 19th-century Scottish engineer and physicist William Rankine, although it has links to the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle's concept of potentiality.

In mechanics and physics, simple harmonic motion is a special type of periodic motion an object experiences due to a restoring force whose magnitude is directly proportional to the distance of the object from an equilibrium position and acts towards the equilibrium position. It results in an oscillation that is described by a sinusoid which continues indefinitely.

Young's modulus is a mechanical property of solid materials that measures the tensile or compressive stiffness when the force is applied lengthwise. It is the modulus of elasticity for tension or axial compression. Young's modulus is defined as the ratio of the stress applied to the object and the resulting axial strain in the linear elastic region of the material.

In physics, Hooke's law is an empirical law which states that the force needed to extend or compress a spring by some distance scales linearly with respect to that distance—that is, Fs = kx, where k is a constant factor characteristic of the spring, and x is small compared to the total possible deformation of the spring. The law is named after 17th-century British physicist Robert Hooke. He first stated the law in 1676 as a Latin anagram. He published the solution of his anagram in 1678 as: ut tensio, sic vis. Hooke states in the 1678 work that he was aware of the law since 1660.

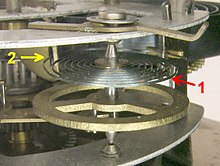

A coil spring is a type of spring made out of a long piece of metal that is wound around itself. Coil springs were in use in Roman times, evidence of this can be found in bronze Fibulae — the clasps worn by Roman soldiers among others. These are quite commonly found in Roman archeological digs.

Stiffness is the extent to which an object resists deformation in response to an applied force.

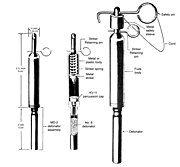

A torsion spring is a spring that works by twisting its end along its axis; that is, a flexible elastic object that stores mechanical energy when it is twisted. When it is twisted, it exerts a torque in the opposite direction, proportional to the amount (angle) it is twisted. There are various types:

In structural engineering, buckling is the sudden change in shape (deformation) of a structural component under load, such as the bowing of a column under compression or the wrinkling of a plate under shear. If a structure is subjected to a gradually increasing load, when the load reaches a critical level, a member may suddenly change shape and the structure and component is said to have buckled. Euler's critical load and Johnson's parabolic formula are used to determine the buckling stress of a column.

Euler–Bernoulli beam theory is a simplification of the linear theory of elasticity which provides a means of calculating the load-carrying and deflection characteristics of beams. It covers the case corresponding to small deflections of a beam that is subjected to lateral loads only. By ignoring the effects of shear deformation and rotatory inertia, it is thus a special case of Timoshenko–Ehrenfest beam theory. It was first enunciated circa 1750, but was not applied on a large scale until the development of the Eiffel Tower and the Ferris wheel in the late 19th century. Following these successful demonstrations, it quickly became a cornerstone of engineering and an enabler of the Second Industrial Revolution.

Elastic energy is the mechanical potential energy stored in the configuration of a material or physical system as it is subjected to elastic deformation by work performed upon it. Elastic energy occurs when objects are impermanently compressed, stretched or generally deformed in any manner. Elasticity theory primarily develops formalisms for the mechanics of solid bodies and materials. The elastic potential energy equation is used in calculations of positions of mechanical equilibrium. The energy is potential as it will be converted into other forms of energy, such as kinetic energy and sound energy, when the object is allowed to return to its original shape (reformation) by its elasticity.

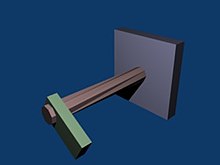

In physics, tension is described as the pulling force transmitted axially by the means of a string, a rope, chain, or similar object, or by each end of a rod, truss member, or similar three-dimensional object; tension might also be described as the action-reaction pair of forces acting at each end of said elements. Tension could be the opposite of compression.

In physics and mathematics, in the area of dynamical systems, an elastic pendulum is a physical system where a piece of mass is connected to a spring so that the resulting motion contains elements of both a simple pendulum and a one-dimensional spring-mass system. For specific energy values, the system demonstrates all the hallmarks of chaotic behavior and is sensitive to initial conditions.At very low and very high energy, there also appears to be regular motion. The motion of an elastic pendulum is governed by a set of coupled ordinary differential equations.This behavior suggests a complex interplay between energy states and system dynamics.

Structural engineering depends upon a detailed knowledge of loads, physics and materials to understand and predict how structures support and resist self-weight and imposed loads. To apply the knowledge successfully structural engineers will need a detailed knowledge of mathematics and of relevant empirical and theoretical design codes. They will also need to know about the corrosion resistance of the materials and structures, especially when those structures are exposed to the external environment.

Carbon nanotube springs are springs made of carbon nanotubes (CNTs). They are an alternate form of high-density, lightweight, reversible energy storage based on the elastic deformations of CNTs. Many previous studies on the mechanical properties of CNTs have revealed that they possess high stiffness, strength and flexibility. The Young's modulus of CNTs is 1 TPa and they have the ability to sustain reversible tensile strains of 6% and the mechanical springs based on these structures are likely to surpass the current energy storage capabilities of existing steel springs and provide a viable alternative to electrochemical batteries. The obtainable energy density is predicted to be highest under tensile loading, with an energy density in the springs themselves about 2500 times greater than the energy density that can be reached in steel springs, and 10 times greater than the energy density of lithium-ion batteries.

Contact mechanics is the study of the deformation of solids that touch each other at one or more points. This can be divided into compressive and adhesive forces in the direction perpendicular to the interface, and frictional forces in the tangential direction. Frictional contact mechanics is the study of the deformation of bodies in the presence of frictional effects, whereas frictionless contact mechanics assumes the absence of such effects.

The acoustoelastic effect is how the sound velocities of an elastic material change if subjected to an initial static stress field. This is a non-linear effect of the constitutive relation between mechanical stress and finite strain in a material of continuous mass. In classical linear elasticity theory small deformations of most elastic materials can be described by a linear relation between the applied stress and the resulting strain. This relationship is commonly known as the generalised Hooke's law. The linear elastic theory involves second order elastic constants and yields constant longitudinal and shear sound velocities in an elastic material, not affected by an applied stress. The acoustoelastic effect on the other hand include higher order expansion of the constitutive relation between the applied stress and resulting strain, which yields longitudinal and shear sound velocities dependent of the stress state of the material. In the limit of an unstressed material the sound velocities of the linear elastic theory are reproduced.