Tropical cyclone warnings and watches are alerts issued by national weather forecasting bodies to coastal areas threatened by the imminent approach of a tropical cyclone of tropical storm or hurricane intensity. They are notices to the local population and civil authorities to make appropriate preparation for the cyclone, including evacuation of vulnerable areas where necessary. It is important that interests throughout the area of an alert make preparations to protect life and property, and do not disregard it on the strength of the detailed forecast track.

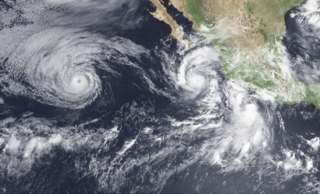

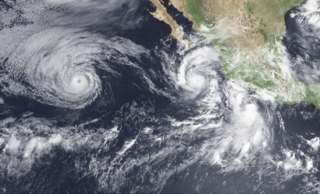

A Pacific hurricane is a tropical cyclone that develops within the northeastern and central Pacific Ocean to the east of 180°W, north of the equator. For tropical cyclone warning purposes, the northern Pacific is divided into three regions: the eastern, central, and western, while the southern Pacific is divided into 2 sections, the Australian region and the southern Pacific basin between 160°E and 120°W. Identical phenomena in the western north Pacific are called typhoons. This separation between the two basins has a practical convenience, however, as tropical cyclones rarely form in the central north Pacific due to high vertical wind shear, and few cross the dateline.

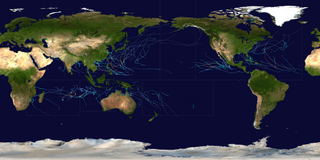

An Atlantic hurricane is a type of tropical cyclone that forms in the Atlantic Ocean primarily between June and November. The terms "hurricane", "typhoon", and "cyclone" can be used interchangeably to describe this weather phenomenon. These storms are rotating, organized systems of clouds and thunderstorms that originate over tropical or subtropical waters and have closed low-level circulation, not to be confused with tornadoes. They form over low pressure systems. In the North Atlantic, central North Pacific, and eastern North Pacific, the term "hurricane" is mainly used, whereas "typhoon" is more commonly used for storms originating in the western North Pacific. The term "cyclone" is used in the South Pacific and Indian Ocean.

Tropical cyclogenesis is the development and strengthening of a tropical cyclone in the atmosphere. The mechanisms through which tropical cyclogenesis occurs are distinctly different from those through which temperate cyclogenesis occurs. Tropical cyclogenesis involves the development of a warm-core cyclone, due to significant convection in a favorable atmospheric environment.

In the south-west Indian Ocean, tropical cyclones form south of the equator and west of 90° E to the coast of Africa.

The 1973 North Indian Ocean cyclone season was part of the annual cycle of tropical cyclone formation. The season has no official bounds but cyclones tend to form between April and December. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northern Indian Ocean. There are two main seas in the North Indian Ocean—the Bay of Bengal to the east of the Indian subcontinent and the Arabian Sea to the west of India. The official Regional Specialized Meteorological Centre in this basin is the India Meteorological Department (IMD), while the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) releases unofficial advisories. An average of five tropical cyclones form in the North Indian Ocean every season with peaks in May and November. Cyclones occurring between the meridians 45°E and 100°E are included in the season by the IMD.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to tropical cyclones:

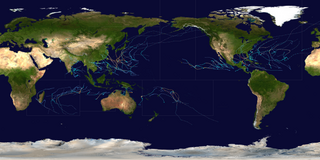

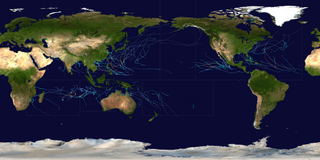

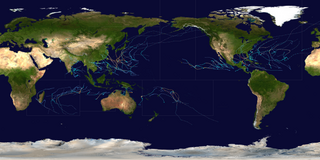

During 2010, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. During the year, a total of 111 tropical cyclones developed, with 64 of them being named by either a Regional Specialized Meteorological Center (RSMC) or a Tropical Cyclone Warning Center (TCWC). The most active basin was the North Atlantic, which documented 19 named systems, while the North Indian Ocean, despite only amounting to five named systems, was its basin's most active since 1998. Conversely, both the West Pacific typhoon and East Pacific hurricane seasons experienced the fewest cyclones reaching tropical storm intensity in recorded history, numbering 14 and 8, respectively. Activity across the southern hemisphere's three basins—South-West Indian, Australian, and South Pacific—was spread evenly, with each region recording 7 named storms apiece. The southern hemisphere's strongest tropical cyclone was Cyclone Edzani, which bottomed out with a barometric pressure of 910 mbar in the South-West Indian Ocean. Nineteen Category 3 tropical cyclones formed, including four Category 5 tropical cyclones in the year. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2010, as calculated by Colorado State University was 573.8 units.

During 2005, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. During the year, a total of 141 systems formed with 94 of these developing further and were named by the responsible warning centre. The strongest tropical cyclone of the year was Hurricane Wilma, which was estimated to have a minimum barometric pressure of 882 hPa (26.05 inHg). 2005 was above-average in terms of the number of storms. The most active basin in the year was the North Atlantic, which documented 28 named systems. The Western Pacific had an near-average season with 23 named storms. The Eastern Pacific hurricane season experienced an above-average number of tropical storm intensity systems, numbering 15. Activity across the southern hemisphere's three basins – South-West Indian, Australian, and South Pacific – was fairly significant, with the regions recording 23 named storms altogether, with the most intense Southern Hemisphere cyclone of the year, Cyclone Percy from the South Pacific Ocean basin peaking at 145 mph (235 km/h) and 900 millibars. Throughout the year, 28 Category 3 tropical cyclones formed, including eight Category 5 tropical cyclones in the year. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2005, as calculated by Colorado State University was 899.6 units.

Throughout 2006, 133 tropical cyclones formed in seven bodies of water known as tropical cyclone basins. Of these, 80 have been named, including two tropical cyclones in the South Atlantic Ocean, and a tropical cyclone in the Mediterranean Sea, by various weather agencies when they attained maximum sustained winds of 65 km/h (40 mph). The strongest storms of the year were Typhoon Yagi in the Western Pacific, and Cyclone Glenda of the Australian region. The deadliest and costliest storms of the year were a series of five typhoons that struck the Philippines and China; Chanchu, Bilis, Saomai, Xangsane, and Durian, with most of the damage being caused by Durian of November. So far, 27 Category 3 tropical cyclones formed, including five Category 5 tropical cyclones in the year. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2006, as calculated by Colorado State University was 761 units.

During 2018, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. During the year, a total of 151 tropical cyclones had formed this year to date. 102 tropical cyclones were named by either a Regional Specialized Meteorological Center (RSMC) or a Tropical Cyclone Warning Center (TCWC).

During 2004, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. During the year, a total of 132 systems formed with 82 of these developing further and were named by the responsible warning centre. The strongest tropical cyclone of the year was Cyclone Gafilo, which was estimated to have a minimum barometric pressure of 895 hPa (26.43 inHg). The most active basin in the year was the Western Pacific, which documented 29 named systems, while the North Atlantic 15 named systems formed. Conversely, both the Eastern Pacific hurricane and North Indian Ocean cyclone seasons experienced a below average number of named systems, numbering 12 and 4, respectively. Activity across the southern hemisphere's three basins—South-West Indian, Australian, and South Pacific—was spread evenly, with each region recording seven named storms apiece. Throughout the year, 28 Category 3 tropical cyclones formed, including seven Category 5 tropical cyclones formed in the year. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2004, as calculated by Colorado State University was 1024.4 units.

During 2000, tropical cyclones formed in seven different areas called basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. A total of 140 tropical cyclones formed within bodies of water known as tropical cyclone basins, with 81 of them being further named by their responsible weather agencies when they attained maximum sustained winds of 35 knots. The strongest storm of the year was Cyclone Hudah, peaking with a minimum pressure of 905 hPa (26.72 inHg), and with 10-minute sustained winds of 220 km/h (135 mph). The highest confirmed number of deaths from a storm was from Typhoon Kai-tak, which killed 188 people, however, Leon–Eline may have killed up to 722 people. The costliest storm was Saomai, which caused $6.3 billion in damage. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2000, as calculated by Colorado State University was 677.3 units.

The year 1997 was regarded as one of the most intense tropical cyclone years on record, featuring a record 12 category 5-equivalent tropical cyclones, according to the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale. The year also featured the second-highest amount of accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) on record, just behind 1992 and 2018. Throughout the year, 108 tropical cyclones have developed in bodies of water, commonly known as tropical cyclone basins. However, only 89 tropical cyclones were of those attaining 39 mph or greater, falling just below the long term average of 102 named systems. The most active basin was the Western Pacific, attaining an ACE amount of 571, the highest ever recorded in any season in any basin on record. The deadliest tropical cyclone was Severe Tropical Storm Linda (Openg). The costliest tropical cyclone was Super Typhoon Winnie (Ibiang), which set a record for having the largest eye on record. The most intense tropical cyclone was Hurricane Linda, peaking at 902 hPa/mbar. Typhoon Paka (Rubing), the longest-lived system, produced the fourth-highest ACE for a single tropical cyclone, just behind Typhoon Nancy (1961), Hurricane/Typhoon Ioke (2006), and Cyclone Freddy (2023). The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 1997, as calculated by Colorado State University was 1,099.2 units.

During 1999, tropical cyclones formed within seven different bodies of water called basins. To date, 142 tropical cyclones formed in bodies of water known as tropical cyclone basins, of which 72 were given names by various weather agencies. The strongest tropical cyclone of the year was Gwenda, attaining maximum sustained winds of 120 knots and a pressure of 900 hPa (26.58 inHg), later tied with Inigo in 2003. Floyd was the costliest tropical cyclone of the year, with around $6.5 billion worth of damages as it affected the Bahamas, the East Coast of the United States, and the Atlantic Canada. The deadliest cyclone of this year was the 1999 Odisha cyclone, which was blamed for over 9,667 deaths as it devastated India. It was also the strongest Northern Hemisphere cyclone of the year with the pressure of 912 hPa (26.93 inHg) and third most intense tropical cyclone worldwide next to Cyclone Gwenda and Cyclone Vance. Three Category 5 tropical cyclones were formed in 1999. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 1999, as calculated by Colorado State University was 606.4 units.

During 1996, tropical cyclones formed within seven different tropical cyclone basins, located within various parts of the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans. During the year, a total of 139 tropical cyclones formed in bodies of water known as tropical cyclone basins. 90 of them were named by various weather agencies when they attained maximum sustained windS of 35 knots. The strongest tropical cyclone of the year was Cyclone Daniella, peaking with a pressure of 915 hPa (27.02 inHg) in the open waters of the Indian Ocean. Hurricane Fran and Typhoon Herb tie for the costliest storm of the year, both with a damage cost of $5 billion. The deadliest tropical cyclone of the year was the 1996 Andhra Pradesh cyclone, which was blamed for over 1,000 fatalities as it directly affected the state of Andhra Pradesh in India. Five Category 5 tropical cyclones were formed in 1996. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 1996, as calculated by Colorado State University was 960 units.

During 1993, tropical cyclones formed within seven different bodies of water called basins. To date, 110 tropical cyclones formed, of which 78 were given names by various weather agencies. Only one Category 5 tropical cyclone was formed in 1993. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 1993, as calculated by Colorado State University was 710.4 units.

During 2021, tropical cyclones formed in seven major bodies of water, commonly known as tropical cyclone basins. Tropical cyclones will be assigned names by various weather agencies if they attain maximum sustained winds of 35 knots. During the year, one hundred forty-five systems have formed and ninety-one were named, including one subtropical depression and excluding one system, which was unofficial. One storm was given two names by the same RSMC. The most intense storm of the year was Typhoon Surigae, with maximum 10-minute sustained wind speeds of 220 km/h (140 mph) and a minimum pressure of 895 hPa (26.43 inHg). The deadliest tropical cyclone was Typhoon Rai, which caused 410 fatalities in the Philippines and 1 in Vietnam, while the costliest was Hurricane Ida, which caused an estimated $75.25 billion USD in damage after striking Louisiana and the Northeastern United States. Six Category 5 tropical cyclones formed during the year, tying 2003. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2021, as calculated by Colorado State University (CSU) was 621.1 units overall.

During 2023, tropical cyclones formed in seven major bodies of water, commonly known as tropical cyclone basins. They were named by various weather agencies when they attained maximum sustained winds of 35 knots. Throughout the year, a total of 115 systems formed, with 79 of them being named. The most intense storm this year was Typhoon Mawar, which had a minimum pressure of 900 hPa (26.58 inHg). The deadliest and costliest tropical cyclone of the year was Storm Daniel, which killed at least 10,028 people in Libya, Greece, Turkey, and Bulgaria, and caused at least US$21.14 billion worth of damage. Among this year's systems, thirty became major tropical cyclones, of which nine intensified into Category 5 tropical cyclones on the Saffir–Simpson scale (SSHWS). This year, for the first time on record, at least one such Category 5 system formed in each tropical cyclone basin: Typhoons Mawar and Bolaven in the western Pacific Ocean, Hurricanes Jova and Otis in the eastern Pacific, Hurricane Lee in the Atlantic, Cyclone Mocha in the North Indian Ocean, Cyclone Freddy in the southwest Indian Ocean, Cyclone Ilsa in the Australian region, and Cyclone Kevin in the South Pacific. The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 2023, as calculated by Colorado State University (CSU) was 857.4 units overall.