Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church | |

| |

| Location | 1137 West St., Parkville, Missouri |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°11′42″N94°41′9″W / 39.19500°N 94.68583°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1907 |

| Architect | Breen, Charles Patrick |

| Architectural style | Late Gothic Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 92001055 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | August 31, 1992 |

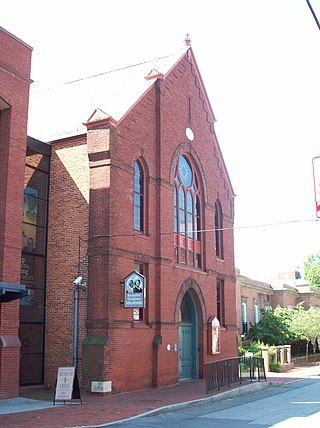

Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church is a historic Christian Methodist Episcopal church located at 1137 West Street in Parkville, Platte County, Missouri. It was built in 1907, and is a two-story, rectangular, Late Gothic Revival style native limestone building. It has a gable roof and features a castellated corner tower and projecting bays. [2] : 5

The Church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1992. [1]

History: Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church Barbara Schell Luetke, Member, Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church April 1, 2024 White settlers and the people they enslaved arrived in Platte County after the Platte Purchase Treaty (ratified in 1837). Resembling Southern plantations, these African Americans grew and harvested labor-intensive hemp, which fostered a rapid economic and population increase. By 1860, Blacks comprised nearly one-quarter of Platte County's population. While very few White settlers could be considered abolitionists, a handful of them opposed slavery in principle, including Parkville's founder, Colonel George S. Park (although he owned enslaved people himself). Enslaved African Americans were rarely allowed to become full members of White churches. Before the Civil War, Platte, Clay, and Jackson Counties, had “slave balconies” in their churches where Black worshippers were allowed to sit (Fuenfhausen, 2023). In smaller churches, African Americans sat in a segregated section (Fuenfhausen, 2023) and were listed in the church records as members. Enslaved African American also worshipped in their own manner in cabins or outdoors, served by both local and itinerant Black ministers (Mutti Burke, 2010). However, before the end of slavery, free African Americans in the North began to create religious institutions separate from their White counterparts. In the late 1700s, Richard Alien formed the Free African Society in Philadelphia, which led to the regional spread of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. In 1844, a split occurred in the Methodist Church over slavery. In the South, enslaved people usually worshiped in the churches of their masters (Powers, 2023), but in the North, Blacks were allowed to organize (Fraser 1954). In these churches, African Americans found an independence and respect that was not possible in White churches. Black churches were one of the few means that Blacks had to express themselves; religion became the heart of their community (Frazier, 1964). Black churches hosted a variety of social activities (Missouri State Parks website). Typical of the situation is an account from the early history of Platte County (of which Parkville is a part) describing the arrest of two Black ministers caught preaching. In 1854, “Charles a slave of Almond Paxton, and Callahan and Andy, slaves of L. C. Jack, were convicted for expounding on the gospel to their fellows with no officer present on Atchison Hill” (in Platte City near the old “Catholic Cemetery” on Atchison Hill). Charles and Andy were fined (Paxton, 1897, p. 187). After the Civil War, the small African American membership, which remained in the Methodist Episcopal Church South, was permitted to organize a separate church. Thus, in 1870, the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (today the Christian Methodist Episcopal, or C.M.E, Church) was formed in Jackson, Tennessee (Fraser 1954; Douglass, 1994). The Colored Methodist Episcopal Church held its first conference in the summer, 1870. Reverend Arch Brown and his cousin, Steven Carter, traveled by horse-drawn wagon from Leavenworth, Kansas to Jackson, Tennessee to attend. They represented a “colored church” in Parkville organized by Moses White, a Black man, of Leavenworth. The Parkville church was said to be the second Colored Methodist Episcopal Church in Missouri (Christian Index, 1950 as reported in Douglass, 1992 in an application to the National Registry of Historic Places). Steve Carter (1851-1926) became an employee at Park College (now Park University) in 1879 working as a ground caretaker. He held the job until his death in 1926. Former Park College President Donald Breckon (1990) described Mr. Carter as the son of a freed slave who supervised construction of homes for freed slaves on George Park’s land [in Parkville], but on the signage posted at the University he is described as being “freed from slavery after the Civil War.” From 1870 to 1877, George Park allowed his enslaved housekeeper, Angeline Rucker (who by 1854 had married Willy Washington) and the other members of Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church to hold services in the northeast corner of the basement of “Old Number 1,” a hotel he owned (Flatland in the series, “Parkville Reckons With Its Storied Past” by Catherine Hoffman; also noted in Douglass, 1992}. The hotel was located near the tracks where the Spirit Fountain is at 8701 River Park Drive. In 1877, the C.M.E. congregation “was moved across the street [from the hotel] to a brick structure” (Douglass, 1992). This is presumed to be the No. 4 in Block 41 lot discussed in the next paragraph. The membership appears to have grown rapidly, because as early as 1886, the Park College Record (August 17, 1886). noted that, “For some time the Colored people of town have been trying to raise means to erect a church, the present [space] having become too small and old for their use. This week they have purchased the ruins of the old [Park] College barn, and will use the timbers, which are very heavy and solid, in building their new house of worship. Charter members of Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church included Andrew Jackson, Wade and Amanda Sanders, and Willy and Angeline Washington. Also, the Bolden and Nichols families. Surely, Steven Carter, who had made the trip to Tennessee to ask that the Church be recognized, was also a member. Lewis and Armenta Cave also were early members, joining about 1872 according to the Kansas–Missouri Annual Conference Record (September 1946, in Douglass, 1992). Their son, Spencer Taylor Cave (1862-1947), became a beloved employee of Park College. According to Dr. Timothy Westcott, Professor of History at Park University, Spencer’s parents belonged to owners named Craig and Cave in Kentucky. The Cave family was sold to the Graves family in Slater, Missouri, working on the Graves Plantation until 1866 (Missouri's enslaved people were freed on January 11, 1865). The family traveled by steamboat to Westport Landing (Kansas City, Missouri). Spencer stayed in the area while his father went on to Canada. From the age of seventeen years, Spencer was employed by Park College. He was an active member of Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church, serving in many capacities, including Sunday School Superintendent for over forty years. At some point Park College established the “Spencer Cave Lecture Series.” For several years a guest speaker gave lectures during Black History Month. The Minutes of the Board of Trustees of June 18, 1905, stated that, “On motion, H.B. McAfee was authorized to negotiate an exchange with the C.M.E. Church of Parkville, trading No. 4 in Block 41 lot, for a parcel of ground (i.e., 1137 West Street} near the Banneker School for Colored Children at the end of West Street. Blacks who lived in the area referred to this area as “the Hollow.” The land had originally been planned as an annex for an African American college, but the dream had been forsaken. At the time of Church construction in 1907, 1137 West Street was still owned by Park College (Standard atlas of Platte County, Missouri 1907). A Trust Agreement dated June 10, 1907, listed the purchase price for the property to be $1,866.40. The money was loaned to the Church by Park College, and paid back over the years (Standard atlas of Platte County, Missouri 1907). The traded lot on West Street was four times as large as the former Church location at 10th and Main Streets. The purpose of the land transaction described above provided a location for a larger facility for the C.M.E. Church and moved it out of downtown Parkville. According to the oral history of Alcorama Douglass Spencer and Cora Douglass Thompson, the congregation was moved “because the White residents of Parkville wanted the Black people off of Main Street.” Dr. Westcott wrote otherwise: “A sense of community was being formed by the Banneker School and the … C.M.E. Church, so moving to the general geographical location of these institutions and the general communal nature was not racial any more than Italians residing in ‘Little Italy’s’ or other ethnic groups living in ethnic ghettos” (Westcott in an email to Luetke; June, 2022). [For information about the Banneker School, see the foundation website (The History of the Banneker School, https://bannekerschoolparkvillemo.org/history). At some point, the C.M.E. Church became a Methodist church --named for Willy and Angeline Washington. Nearby, Mount Washington Baptist Church (West 11th Street and now a private home) was established by Willie's cousin, George Washington. It remains unclear exactly who was responsible for the design of Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church (Douglass, 1992). It is in a simpler style of the late Gothic Revival style (Whiffen, 1985 in Douglass, 1992). Although the church windows do not have the typical Gothic arch, the top and bottom of the windows are emphasized by fine stonework. The castellated tower on the northeast corner of the church brings verticality in design and adds to the massive appearance of the building (Douglass, 1992). Native limestone was quarry from the Park College grounds, as well as the hill on which the Church sits. Some of the Park College students helped with the construction, but the majority of the labor was provided by the men of the congregation (Douglass, 1992). Construction of the Church was supervised by Charles “Pat” Patrick Breen, the Superintendent of Buildings at Park College (An Architectural/Historic Survey of Parkville, Missouri; June 1994). He was working across the river at Quindaro when he was approached about work on campus. Taking the job, he worked largely with student labor, demonstrating not only a talent for stonemasonry, but also patience and the ability to educate students. Breen stayed on as Superintendent of Construction at Park College until 1909, and was responsible for more than a dozen significant structures on campus, as well as for construction in the City of Parkville and surrounding towns (April 9, 1899, Park College Record in Douglass, 1992; Platte County Gazette, December 16, 1938). The quality of his craftsmanship was evidenced in the Washington Chapel Church, although the building is not typically mentioned as one of his projects (Douglass, 1992). Douglass attributed this to the racism of the period in which Breen lived. Nevertheless, Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church stands today as a tribute to a stonemason who was able to impact his craft to Park College students and the men of the Washington Chapel Church (Charles P, Brennan vertical file cited in Douglass 1992). The building was described by Parkville Mayor Kathryn Dusenbery in a 2007 proclamation as a “beautiful landmark.” On October 28, 1886, it was reported in the Parkville Independent that “the foundation for a Colored church in Parkville is partly in and the congregation is asking the people of Parkville to assist them in [financing the] building the structure.” Douglass (1992) reported that there was considerable effort to raise funds for the church structure, ranging from special events held at Park College to member pledges. Construction continued until 1905 (Platte Shopper News, October 17, 1984). In May, 1905, Parkville citizens attended two public lectures in the McCormick Chapel (at Park College). “The worthy object of the lectures was aiding to raise funds to build a new Colored M.E. Church. We do not hesitate to say that the Colored community of Parkville is far above the average in sobriety, industry, thrift and intelligence. When Park College had reached such a degree of financial prosperity that it was possible to hire the help which is so largely necessary in work with teams . . . Colored help was the chief help obtainable” (Westcott, 2022, Banneker fundraiser luncheon, Parkville, MO). About this same time, a Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church parsonage was built on 13th and Elm (where a yellow house stands today). Alcorama Douglass Spencer and Cora Douglass Thompson remember that it had a parlor with a good stove, two bedrooms, and no indoor plumping. Reverends Kneely, Johnson, Jenkins, and James Smith, the Pastor of Mount Washington Baptist Church, lived there with their families. Other reverends that served the Church are listed in a 2018 commemorative Church calendar, with the exception of Reverend Lewis who served in 2019 and 2020. Dr. McAfee died before Washington Chapel C.M.E. Church became a reality. His son, Howard McAfee, arranged for a stained-glass window that had been in the original Chapel (that had burned down) to be installed in his memory. His father, Howard McAfee, had taken a special interest in the Washington Chapel congregation, as many of its members were employees of Park College. On January 21, 2023, thieves broke the John McAfee Memorial Window and stole the part of the glass that contained Dr. McAfee’s name. The piece was miraculously returned the morning of a “vigil of forgiveness” that was held in the Church yard. Over 2023 and 2024, funds were raised to replace it. On October 4, 1906, the Platte County Gazette noted that “The new stone church for the C.M.E. congregation is rapidly nearly completion.” The congregation held its first service in the new Church on February 24, 1907. “It was seated with oak pews constructed by Mr. Thad Ashby,” who also worked on many of the homes in the segregated hollow. “They reflect good credit on him as a cabinet workman. The lower floor of the building will be used for festivals, public gatherings, and so forth. It is a large room with concrete floor and is well adapted to the purposes for which it is to be used … It is a good building and reflects credit on the congregation” (Platte County Gazette; October 4, 1906). The Washington Chapel C. M.E. Church was dedicated on June 29, 1907, as engraved in the Church cornerstone. Initially, the Church boasted eighty members, fifty-six of them pledging to give a tenth of their income to sustain it (Douglass, 1994). According to the Douglass application to the National Registry of Historic Places, the leaders of the Church were also members of the leading African American families in Parksville. Among the names of these important people were Carter, Cave, Bolden, Brown, Jackson, Martin, Nichols, Pearl, Rogers, and Woods. The Reverends Yates and Anderson played early important roles in both the Church and the integration history of Park College. While not allowed to register and receive credit for classes in which they participated, these community leaders, including Lucille Sears Douglass, were allowed to attend classes and completed course requirements as early as 1938 (Breckon, 1990). Records indicate that payments were made over the years on the loan that Park College made to the Church (Westcott, 2022). On October 1951, the final transfer of ownership for the land building actually occurred and the College Board of Trustees conveyed the property to the trustees of the colored Methodist Episcopal Church (Douglass, 1992). Additional stained-glass windows were installed in 1953. They have the following dedications: the east window in the tower, "Community Youth Club"; on the north elevation, from east to west - "Mrs. Lucy Frazier" - "Charter Members Mrs. William Washington, Mr. & Mrs. Wade Saunders, Andrew Jackson", "First Stewards Louis Nichols, Richard Rogers, Spencer Cave, Robert Carter, Otis Washington, Charlie Brown", "First Trustees George Bolden, Ruben Martin, Alien Little, Arch Brown, Richard Rogers", "Bishops W.H. Miles, Joseph Beebe, I. Lane, N.C. Cleaves, M.F. Jamison, J.A. Hamlett" - "in Memoriam George and Kate Bolden" - "Rev. & Mrs. R.A. Simpson"; on the west elevation, from north to south - "In Memory of Alfred & Sarah Johnson by Pansey Stephens & Pearl Mosley" - "In Memory of Vivian Cave Johnson" - "In Memory of Marian E. Brown"; and on the south facade, the grouping of three windows contains a dedication in the center "In Memory of Leonard Clayton 33 Yrs. Steward", which is flanked by "Willing Workers" on the left, and "Morning Glories" on the right. In addition to their prominence due to the effect of the stained glass, the windows are further emphasized by their deeply recessed openings, particularly on the triple windows on the south (Douglass, 1992). Washington Chapel C. M. E. Church was, and is today, the spiritual, social, and visual focal point of Parkville’s African American community (Douglass, 1992). Denied participation in a city that equaled that of the White residents, the Church provided leadership opportunities that included the Trustees, Steward, and the Stewardess Boards, the Choir, the Sunday School, the Missionary Society, the War Mothers and Wives, the Usher Board, the Young People’s Choir, and the Junior Stewards (Douglass, 1992). Vacation Bible School and the Family Institute were held throughout the 1950s and 60s. Many people living in the area today remember attending the annual Easter Breakfast that began during the Depression and the Thanksgiving dinner. These events, as well as fish fries, pancake breakfasts, and the Homecoming Bazaar helped to meet Church expenses. Shan Chi Chek’s grandson was a guest speaker at the Church on several occasions and Alex Haley, acclaimed author of the novel Roots, visited the church in the 1960s, 1977, and 1986 (Graham, 1992; Cora Thompson). Lucille S. Douglass helped to organize annual celebrations for Martin Luther King’s birthday. A veterans’ recognition service was held, and the honoring of those who serve is an important aspect of the Church today. Foreign students from Park College, especially the Japanese students, often joined the worship. As a result of these many activities, the Church left its imprint on everyone in the Parkville community . After World War II, African American service members routinely moved to large cities instead of small towns or rural locations, leaving Black churches with declining memberships (Powers, 2023); This was somewhat the case in Parkville when many Black families migrated to urban centers, seeking relief from the discrimination and segregation of Parkville, MO. In 1992, Lucille Sears Douglass completed the research and application so that Washington Chapel C. M. E. was listed on the National Register of Historic Places (without which this article couldn’t have been written). In recent years, the remaining few, elderly members of Washington Chapel C. M. E. Church have stayed active. In the early 1990s, a description of the Church was made available on Wikipedia. Also, an interior staircase was built so that people did not have to go outside to go from the basement to the sanctuary on the second floor. Lucille H. Douglass (daughter of Lucille S. Douglass) created a Facebook page around 2019. Church members have tried to maintain the Church, but the state of the building became such that members could not hold services and community events in it. Services ended completely before the Pandemic of 2020. After a $160,000 grant was awarded from the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund, a program from the National Trust for Historic Preservation in 2023, the Washington Chapel Restoration Committee was formed of those working directly on the project. The grant money is being used to replace the roof and create a bathroom that is handicapped accessible. These are only a few of the repairs needed to make the building usable again for religious services and community events. The Church building is appraised to need at least $750,000 to be complete restored. The electricity, bell tower, ceiling and walls, floors, and kitchen need to be repaired or replaced. Building supplies are needed. A lift for the interior stairs is needed. Outside, the original brickwork and the sidewalk need to be restored, as well as a second entrance and sidewalk added. Donations can be made to Washington Chapel CME Church 1137 West St. Parkville, Mo. 64152; paypal.me/washchapel or Cashapp ($washchapel). Members of the Church are available to speak to religious and community groups. For questions and references for this article, please contact Barbara Schell Luetke via Facebook.