Dieting is the practice of eating food in a regulated way to decrease, maintain, or increase body weight, or to prevent and treat diseases such as diabetes and obesity. As weight loss depends on calorie intake, different kinds of calorie-reduced diets, such as those emphasising particular macronutrients, have been shown to be no more effective than one another. As weight regain is common, diet success is best predicted by long-term adherence. Regardless, the outcome of a diet can vary widely depending on the individual.

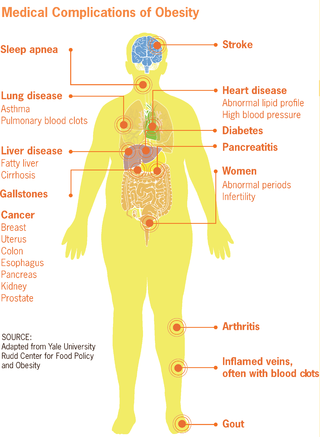

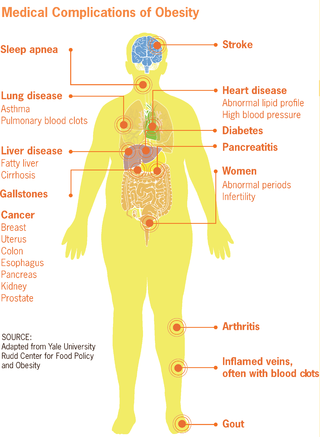

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it can potentially have negative effects on health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's weight divided by the square of the person's height—is over 30 kg/m2; the range 25–30 kg/m2 is defined as overweight. Some East Asian countries use lower values to calculate obesity. Obesity is a major cause of disability and is correlated with various diseases and conditions, particularly cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, certain types of cancer, and osteoarthritis.

Weight loss, in the context of medicine, health, or physical fitness, refers to a reduction of the total body mass, by a mean loss of fluid, body fat, or lean mass. Weight loss can either occur unintentionally because of malnourishment or an underlying disease, or from a conscious effort to improve an actual or perceived overweight or obese state. "Unexplained" weight loss that is not caused by reduction in calorific intake or increase in exercise is called cachexia and may be a symptom of a serious medical condition.

Low-carbohydrate diets restrict carbohydrate consumption relative to the average diet. Foods high in carbohydrates are limited, and replaced with foods containing a higher percentage of fat and protein, as well as low carbohydrate foods.

The Mediterranean diet is a diet inspired by the eating habits and traditional food typical of southern Spain, southern Italy, and Crete, and formulated in the early 1960s. It is distinct from Mediterranean cuisine, which covers the actual cuisines of the Mediterranean countries. While inspired by a specific time and place, the "Mediterranean diet" was later refined based on the results of multiple scientific studies.

A plant-based diet is a diet consisting mostly or entirely of plant-based foods. Plant-based diets encompass a wide range of dietary patterns that contain low amounts of animal products and high amounts of fiber-rich plant products such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, legumes, nuts and seeds. They do not need to be vegan or vegetarian but are defined in terms of low frequency of animal food consumption.

Strength training, also known as weight training or resistance training, involves the performance of physical exercises that are designed to improve strength and endurance. It is often associated with the lifting of weights. It can also incorporate a variety of training techniques such as bodyweight exercises, isometrics, and plyometrics.

A high-protein diet is a diet in which 20% or more of the total daily calories comes from protein. Many high protein diets are high in saturated fat and restrict intake of carbohydrates.

A very-low-calorie diet (VLCD), also known as semistarvation diet and crash diet, is a type of diet with very or extremely low daily food energy consumption. VLCDs are defined as a diet of 800 kilocalories (3,300 kJ) per day or less. Modern medically supervised VLCDs use total meal replacements, with regulated formulations in Europe and Canada which contain the recommended daily requirements for vitamins, minerals, trace elements, fatty acids, protein and electrolyte balance. Carbohydrates may be entirely absent, or substituted for a portion of the protein; this choice has important metabolic effects. Medically supervised VLCDs have specific therapeutic applications for rapid weight loss, such as in morbid obesity or before a bariatric surgery, using formulated, nutritionally complete liquid meals containing 800 kilocalories or less per day for a maximum of 12 weeks.

Bariatric surgery is a medical term for surgical procedures used to manage obesity and obesity-related conditions. Long term weight loss with bariatric surgery may be achieved through alteration of gut hormones, physical reduction of stomach size, reduction of nutrient absorption, or a combination of these. Standard of care procedures include Roux en-Y bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, from which weight loss is largely achieved by altering gut hormone levels responsible for hunger and satiety, leading to a new hormonal weight set point.

The obesity paradox is the finding in some studies of a lower mortality rate for overweight or obese people within certain subpopulations. The paradox has been observed in people with cardiovascular disease and cancer. Explanations for the paradox range from excess weight being protective to the statistical association being caused by methodological flaws such as confounding, detection bias, reverse causality, or selection bias.

Intermittent fasting is any of various meal timing schedules that cycle between voluntary fasting and non-fasting over a given period. Methods of intermittent fasting include alternate-day fasting, periodic fasting, such as the 5:2 diet, and daily time-restricted eating.

Obesity is a risk factor for many chronic physical and mental illnesses.

Management of obesity can include lifestyle changes, medications, or surgery. Although many studies have sought effective interventions, there is currently no evidence-based, well-defined, and efficient intervention to prevent obesity.

A person's waist-to-height ratio (WHtR), occasionally written WtHR or called waist-to-stature ratio (WSR), is defined as their waist circumference divided by their height, both measured in the same units. It is used as a predictor of obesity-related cardiovascular disease. The WHtR is a measure of the distribution of body fat. Higher values of WHtR indicate higher risk of obesity-related cardiovascular diseases; it is correlated with abdominal obesity.

Metabolically healthy obesity or metabolically-healthy obesity (MHO) is a disputed medical condition characterized by obesity which does not produce metabolic complications.

Normal weight obesity is the condition of having normal body weight, but with a high body fat percentage, leading to some of the same health risks as obesity.

The association between obesity, as defined by a body mass index of 30 or higher, and risk of a variety of types of cancer has received a considerable amount of attention in recent years. Obesity has been associated with an increased risk of esophageal cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, endometrial cancer, kidney cancer, thyroid cancer, liver cancer and gallbladder cancer. Obesity may also lead to increased cancer-related mortality. Obesity has also been described as the fat tissue disease version of cancer, where common features between the two diseases were suggested for the first time.

The Summermatter cycle is a physiological concept describing the complex relationship between physical activity/inactivity and energy expenditure/conservation.

Intuitive eating is an approach to eating that focuses on the body's response to cues of hunger and satisfaction. It aims to foster a positive relationship with food as opposed to pursuing "weight control". Additionally, intuitive eating aims to change users' views about dieting, health, and wellness, instilling a more holistic approach. It also helps to create a positive attitude and relationship towards food, physical activity, and the body.