Dieting is the practice of eating food in a regulated way to decrease, maintain, or increase body weight, or to prevent and treat diseases such as diabetes and obesity. As weight loss depends on calorie intake, different kinds of calorie-reduced diets, such as those emphasising particular macronutrients, have been shown to be no more effective than one another. As weight regain is common, diet success is best predicted by long-term adherence. Regardless, the outcome of a diet can vary widely depending on the individual.

Obesity is a medical condition, sometimes considered a disease, in which excess body fat has accumulated to such an extent that it can potentially have negative effects on health. People are classified as obese when their body mass index (BMI)—a person's weight divided by the square of the person's height—is over 30 kg/m2; the range 25–30 kg/m2 is defined as overweight. Some East Asian countries use lower values to calculate obesity. Obesity is a major cause of disability and is correlated with various diseases and conditions, particularly cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, obstructive sleep apnea, certain types of cancer, and osteoarthritis.

Cachexia is a complex syndrome associated with an underlying illness, causing ongoing muscle loss that is not entirely reversed with nutritional supplementation. A range of diseases can cause cachexia, most commonly cancer, congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, and AIDS. Systemic inflammation from these conditions can cause detrimental changes to metabolism and body composition. In contrast to weight loss from inadequate caloric intake, cachexia causes mostly muscle loss instead of fat loss. Diagnosis of cachexia can be difficult due to the lack of well-established diagnostic criteria. Cachexia can improve with treatment of the underlying illness but other treatment approaches have limited benefit. Cachexia is associated with increased mortality and poor quality of life.

Low-carbohydrate diets restrict carbohydrate consumption relative to the average diet. Foods high in carbohydrates are limited, and replaced with foods containing a higher percentage of fat and protein, as well as low carbohydrate foods.

The Mediterranean diet is a diet inspired by the eating habits and traditional food typical of southern Spain, southern Italy, and Crete, and formulated in the early 1960s. It is distinct from Mediterranean cuisine, which covers the actual cuisines of the Mediterranean countries, and from the Atlantic diet of northwestern Spain and Portugal. While inspired by a specific time and place, the "Mediterranean diet" was later refined based on the results of multiple scientific studies.

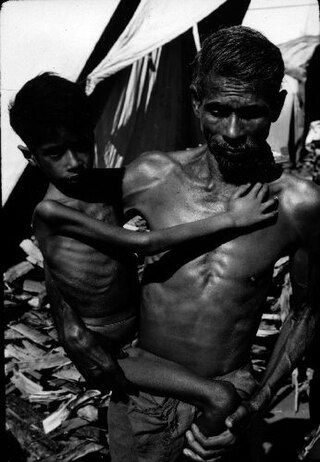

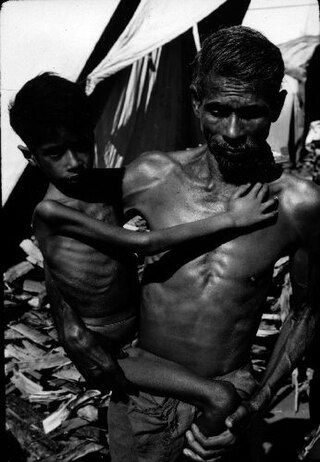

Marasmus is a form of severe malnutrition characterized by energy deficiency. It can occur in anyone with severe malnutrition but usually occurs in children. Body weight is reduced to less than 62% of the normal (expected) body weight for the age. Marasmus occurrence increases prior to age 1, whereas kwashiorkor occurrence increases after 18 months. It can be distinguished from kwashiorkor in that kwashiorkor is protein deficiency with adequate energy intake whereas marasmus is inadequate energy intake in all forms, including protein. This clear-cut separation of marasmus and kwashiorkor is however not always clinically evident as kwashiorkor is often seen in a context of insufficient caloric intake, and mixed clinical pictures, called marasmic kwashiorkor, are possible. Protein wasting in kwashiorkor generally leads to edema and ascites, while muscular wasting and loss of subcutaneous fat are the main clinical signs of marasmus, which makes the ribs and joints protrude.

Anti-obesity medication or weight loss medications are pharmacological agents that reduce or control excess body fat. These medications alter one of the fundamental processes of the human body, weight regulation, by: reducing appetite and consequently energy intake, increasing energy expenditure, redirecting nutrients from adipose to lean tissue, or interfering with the absorption of calories.

Calorie restriction is a dietary regimen that reduces the energy intake from foods and beverages without incurring malnutrition. The possible effect of calorie restriction on body weight management, longevity, and aging-associated diseases has been an active area of research.

A high-protein diet is a diet in which 20% or more of the total daily calories come from protein. Many high protein diets are high in saturated fat and restrict intake of carbohydrates.

A healthy diet is a diet that maintains or improves overall health. A healthy diet provides the body with essential nutrition: fluid, macronutrients such as protein, micronutrients such as vitamins, and adequate fibre and food energy.

The duodenal switch (DS) procedure, gastric reduction duodenal switch (GRDS), is a weight loss surgery procedure that is composed of a restrictive and a malabsorptive aspect.

A very-low-calorie diet (VLCD), also known as semistarvation diet and crash diet, is a type of diet with very or extremely low daily food energy consumption. VLCDs are defined as a diet of 800 kilocalories (3,300 kJ) per day or less. Modern medically supervised VLCDs use total meal replacements, with regulated formulations in Europe and Canada which contain the recommended daily requirements for vitamins, minerals, trace elements, fatty acids, protein and electrolyte balance. Carbohydrates may be entirely absent, or substituted for a portion of the protein; this choice has important metabolic effects. Medically supervised VLCDs have specific therapeutic applications for rapid weight loss, such as in morbid obesity or before a bariatric surgery, using formulated, nutritionally complete liquid meals containing 800 kilocalories or less per day for a maximum of 12 weeks.

A diabetic diet is a diet that is used by people with diabetes mellitus or high blood sugar to minimize symptoms and dangerous complications of long-term elevations in blood sugar.

Bariatric surgery is a medical term for surgical procedures used to manage obesity and obesity-related conditions. Long term weight loss with bariatric surgery may be achieved through alteration of gut hormones, physical reduction of stomach size, reduction of nutrient absorption, or a combination of these. Standard of care procedures include Roux en-Y bypass, sleeve gastrectomy, and biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch, from which weight loss is largely achieved by altering gut hormone levels responsible for hunger and satiety, leading to a new hormonal weight set point.

Intermittent fasting is any of various meal timing schedules that cycle between voluntary fasting and non-fasting over a given period. Methods of intermittent fasting include alternate-day fasting, periodic fasting, such as the 5:2 diet, and daily time-restricted eating.

Weight management refers to behaviors, techniques, and physiological processes that contribute to a person's ability to attain and maintain a healthy weight. Most weight management techniques encompass long-term lifestyle strategies that promote healthy eating and daily physical activity. Moreover, weight management involves developing meaningful ways to track weight over time and to identify the ideal body weights for different individuals.

Clinical nutrition centers on the prevention, diagnosis, and management of nutritional changes in patients linked to chronic diseases and conditions primarily in health care. Clinical in this sense refers to the management of patients, including not only outpatients at clinics and in private practice, but also inpatients in hospitals. It incorporates primarily the scientific fields of nutrition and dietetics. Furthermore, clinical nutrition aims to maintain a healthy energy balance, while also providing sufficient amounts of nutrients such as protein, vitamins, and minerals to patients.

Management of obesity can include lifestyle changes, medications, or surgery. Although many studies have sought effective interventions, there is currently no evidence-based, well-defined, and efficient intervention to prevent obesity.

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB) are any beverage with added sugar. They have been described as "liquid candy". Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages have been linked to weight gain and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease mortality. According to the CDC, consumption of sweetened beverages is also associated with unhealthy behaviors like smoking, not getting enough sleep and exercise, and eating fast food often and not enough fruits regularly.

Preventive Nutrition is a branch of nutrition science with the goal of preventing, delaying, and/or reducing the impacts of disease and disease-related complications. It is concerned with a high level of personal well-being, disease prevention, and diagnosis of recurring health problems or symptoms of discomfort which are often precursors to health issues. The overweight and obese population numbers have increased over the last 40 years and numerous chronic diseases are associated with obesity. Preventive nutrition may assist in prolonging the onset of non-communicable diseases and may allow adults to experience more "healthy living years." There are various ways of educating the public about preventive nutrition. Information regarding preventive nutrition is often communicated through public health forums, government programs and policies, or nutritional education. For example, in the United States, preventive nutrition is taught to the public through the use of the food pyramid or MyPlate initiatives.