The Richmond–Petersburg campaign was a series of battles around Petersburg, Virginia, fought from June 9, 1864, to March 25, 1865, during the American Civil War. Although it is more popularly known as the siege of Petersburg, it was not a classic military siege, in which a city is encircled with fortifications blocking all routes of ingress and egress, nor was it strictly limited to actions against Petersburg. The campaign consisted of nine months of trench warfare in which Union forces commanded by Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant assaulted Petersburg unsuccessfully and then constructed trench lines that eventually extended over 30 miles (48 km) from the eastern outskirts of Richmond, Virginia, to around the eastern and southern outskirts of Petersburg. Petersburg was crucial to the supply of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's army and the Confederate capital of Richmond. Numerous raids were conducted and battles fought in attempts to cut off the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad. Many of these battles caused the lengthening of the trench lines.

United States Colored Troops (USCT) were Union Army regiments during the American Civil War that primarily comprised African Americans, with soldiers from other ethnic groups also serving in USCT units. Established in response to a demand for more units from Union Army commanders, USCT regiments, which numbered 175 in total by the end of the war in 1865, constituted about one-tenth of the manpower of the army, according to historian Kelly Mezurek, author of For Their Own Cause: The 27th United States Colored Troops. "They served in infantry, artillery, and cavalry." Approximately 20 percent of USCT soldiers were killed in action or died of disease and other causes, a rate about 35 percent higher than that of white Union troops. Numerous USCT soldiers fought with distinction, with 16 receiving the Medal of Honor. The USCT regiments were precursors to the Buffalo Soldier units which fought in the American Indian Wars.

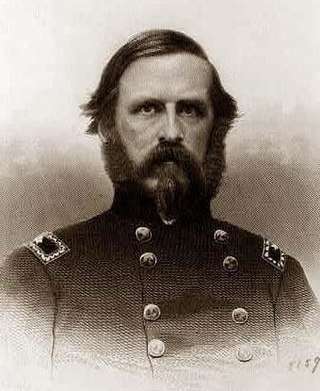

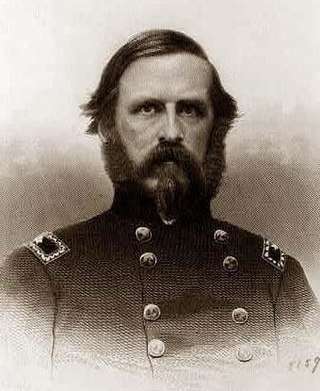

Alfred Howe Terry was a Union general in the American Civil War and the military commander of the Dakota Territory from 1866 to 1869, and again from 1872 to 1886. In 1865, Terry led Union troops to victory at the Second Battle of Fort Fisher in North Carolina.

The Battle of New Bern was fought on March 14, 1862, near the city of New Bern, North Carolina, as part of the Burnside Expedition of the American Civil War. The US Army's Coast Division, led by Brigadier General Ambrose Burnside and accompanied by armed vessels from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, were opposed by an undermanned and badly trained Confederate force of North Carolina soldiers and militia led by Brigadier General Lawrence O'B. Branch. Although the defenders fought behind breastworks that had been set up before the battle, their line had a weak spot in its center that was exploited by the attacking Federal soldiers. When the center of the line was penetrated, many of the militia broke, forcing a general retreat of the entire Confederate force. General Branch was unable to regain control of his troops until they had retreated to Kinston, more than 30 miles away. New Bern came under Federal control, and remained so for the rest of the war.

The Battle of Lewis's Farm was fought on March 29, 1865, in Dinwiddie County, Virginia near the end of the American Civil War. In climactic battles at the end of the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign, usually referred to as the Siege of Petersburg, starting with Lewis's Farm, the Union Army commanded by Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant dislodged the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia commanded by General Robert E. Lee from defensive lines at Petersburg, Virginia and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia. Many historians and the United States National Park Service consider the Battle of Lewis's Farm to be the opening battle of the Appomattox Campaign, which resulted in the surrender of Lee's army on April 9, 1865.

The opening phase of what came to be called the Burnside Expedition, the Battle of Roanoke Island was an amphibious operation of the American Civil War, fought on February 7–8, 1862, in the North Carolina Sounds a short distance south of the Virginia border. The attacking force consisted of a flotilla of gunboats of the Union Navy drawn from the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron, commanded by Flag Officer Louis M. Goldsborough, a separate group of gunboats under Union Army control, and an army division led by Brig. Gen. Ambrose Burnside. The defenders were a group of gunboats from the Confederate States Navy, termed the Mosquito Fleet, under Capt. William F. Lynch, and about 2,000 Confederate soldiers commanded locally by Brig. Gen. Henry A. Wise. The defense was augmented by four forts facing on the water approaches to Roanoke Island, and two outlying batteries. At the time of the battle, Wise was hospitalized, so leadership fell to his second in command, Col. Henry M. Shaw.

The Battle of Appomattox Court House, fought in Appomattox County, Virginia, on the morning of April 9, 1865, was one of the last, and ultimately one of the most consequential, battles of the American Civil War (1861–1865). It was the final engagement of Confederate General in Chief Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia before they surrendered to the Union Army of the Potomac under the Commanding General of the United States Army, Ulysses S. Grant.

The Third Battle of Petersburg, also known as the Breakthrough at Petersburg or the Fall of Petersburg, was fought on April 2, 1865, south and southwest Virginia in the area of Petersburg, Virginia, at the end of the 292-day Richmond–Petersburg Campaign and in the beginning stage of the Appomattox Campaign near the conclusion of the American Civil War. The Union Army under the overall command of General-in-Chief Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, launched an assault on General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia's Petersburg, Virginia, trenches and fortifications after the Union victory at the Battle of Five Forks on April 1, 1865. As a result of that battle the Confederate right flank and rear were exposed. The remaining supply lines were cut and the Confederate defenders were reduced by over 10,000 men killed, wounded, taken prisoner or in flight.

The Appomattox campaign was a series of American Civil War battles fought March 29 – April 9, 1865, in Virginia that concluded with the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia to forces of the Union Army under the overall command of Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, marking the effective end of the war.

The Second Battle of Fort Wagner, also known as the Second Assault on Morris Island or the Battle of Fort Wagner, Morris Island, was fought on July 18, 1863, during the American Civil War. Union Army troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Quincy Gillmore launched an unsuccessful assault on the Confederate fortress of Fort Wagner, which protected Morris Island, south of Charleston Harbor. The battle occurred one week after the First Battle of Fort Wagner. Although it was a Confederate victory, the valor of the Black Union soldiers was widely praised. This had long-term strategic benefits by encouraging more African-Americans to enlist, allowing the Union to utilize a manpower resource that the Confederacy could not match for the remainder of the war.

The Battle of Namozine Church was an engagement in Amelia County, Virginia, between Union Army and Confederate States Army forces that occurred on April 3, 1865, during the Appomattox Campaign of the American Civil War. The battle was the first engagement between units of General Robert E. Lee's Confederate Army of Northern Virginia after that army's evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, Virginia, on April 2, 1865, and units of the Union Army under the immediate command of Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, who was still acting independently as commander of the Army of the Shenandoah, and under the overall direction of Union General-in-Chief Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The forces immediately engaged in the battle were brigades of the cavalry division of Union Brig. Gen. and Brevet Maj. Gen. George Armstrong Custer, especially the brigade of Colonel and Brevet Brig. Gen. William Wells, and the Confederate rear guard cavalry brigades of Brig. Gen. William P. Roberts and Brig. Gen. Rufus Barringer and later in the engagement, Confederate infantry from the division of Maj. Gen. Bushrod Johnson.

Edward Augustus Wild was an American homeopathic doctor and a brigadier general in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

}}

The 6th United States Colored Infantry Regiment was an African American unit of the Union Army during the American Civil War. A part of the United States Colored Troops, the regiment saw action in Virginia as part of the Richmond–Petersburg Campaign and in North Carolina, where it participated in the attacks on Fort Fisher and Wilmington and the Carolinas Campaign.

The 8th Connecticut Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment that fought in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

The New England state of Connecticut played an important role in the American Civil War, providing arms, equipment, technology, funds, supplies, and soldiers for the Union Army and the Union Navy. Several Connecticut politicians played significant roles in the Federal government and helped shape its policies during the war and the Reconstruction.

The town of Greenwich, Connecticut contributed 437 men to twenty-six Connecticut regiments during the American Civil War. Greenwich soldiers fought in almost every major Union campaign, including Bull Run, Gettysburg and the siege of Petersburg. Approximately half of the Greenwich soldiers served in two infantry regiments, the 10th Connecticut Infantry and 17th Connecticut Infantry.

The 67th Ohio Infantry Regiment was an infantry regiment in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

The 49th North Carolina Infantry Regiment was a Confederate States Army regiment during the American Civil War attached to the Army of Northern Virginia.

The 199th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, alternately known as the Commercial Regiment, was an infantry regiment of the Union Army in the American Civil War. Raised in Philadelphia in late 1864, the regiment enlisted for one year and was sent to the Army of the James during the Siege of Petersburg. During the Third Battle of Petersburg it assaulted Forts Gregg and Alexander, then pursued the retreating Confederate Army of Northern Virginia, fighting at Rice's Station and Appomattox Court House. Following the Confederate surrender at Appomattox, the regiment moved to Richmond, where it mustered out in late June 1865.