Forsyth County is a county in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. Suburban and exurban in character, Forsyth County lies within the Atlanta Metropolitan Area. The county's only incorporated city and county seat is Cumming. As of 2019 estimates, the population was 244,252. Forsyth was the fastest-growing county in Georgia and the 15th fastest-growing county in the United States between 2010 and 2019.

Cumming is a city in Forsyth County, Georgia, United States, and the sole incorporated area in the county. It is an exurban city, and part of the Atlanta metropolitan area. Its population was 5,430 at the 2010 census, up from 4,200 in 2000. Surrounding unincorporated areas with a Cumming mailing address have a population of approximately 100,000. Cumming is the county seat of Forsyth County.

Sam Hose, a.k.a. Sam Holt, a.k.a. Samuel "Thomas" Wilkes, né Tom Wilkes was an African American who was tortured and executed by a white lynch mob in Coweta County, Georgia.

Lynching is premeditated murder committed by a group of people by extrajudicial action. Lynchings in the United States first became common in the Southern United States in the 1830s, 1840s, and 1850s, at which time most of the victims were white men. Lynchings of black people rose in number after the American Civil War during Reconstruction; they declined in the 1930s. Most lynchings were of African-American men in the Southern United States, but women and non-blacks were also lynched, not always in the South.

The People's Grocery was a grocery located just outside Memphis in a neighborhood called the "Curve". Opened in 1889, the Grocery was a cooperative venture run along corporate lines and owned by 11 prominent African Americans, including postman Thomas Moss, a friend of Ida B. Wells.

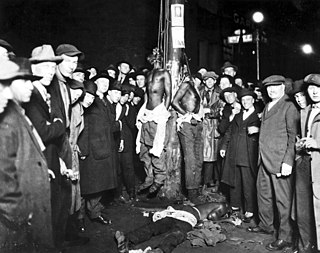

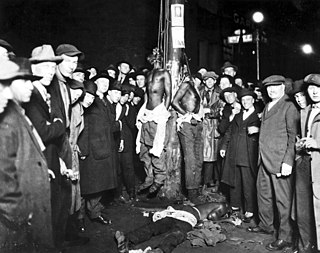

On June 15, 1920, three African-American circus workers, Elias Clayton, Elmer Jackson, and Isaac McGhie, suspects in an assault case, were taken from jail and lynched by a white mob of thousands in Duluth, Minnesota. Rumors had circulated that six African Americans had raped and robbed a nineteen-year-old woman. A physician who examined her found no physical evidence of rape.

The Atlanta Massacre of 1906 was an attack by armed mobs of white Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, which began the evening of September 22 and lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Aberdeen (Scotland) Press and Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London (UK) Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the riots. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lamposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

Roy Belton was an 18-year-old white man arrested in Tulsa, Oklahoma with a female accomplice for the August 21, 1920 hijacking and shooting of a white man Homer Nida, a local taxi driver. He was taken from the county jail by a group of armed men, after a confrontation with the sheriff, and taken to an isolated area where he was lynched. This incident contributed to fears in the black community about treatment by police and whites if any of their members were arrested.

On May 16, 1918, a plantation owner was murdered, prompting a manhunt which resulted in a series of lynchings in May 1918 in southern Georgia, United States. White people killed at least 13 black people during the next two weeks. Among those killed were Hayes and Mary Turner. Hayes was killed on May 18, and the next day, his pregnant wife Mary was strung up by her feet, doused with gasoline and oil then set on fire. Mary's unborn child was cut from her abdomen and stomped to death. Her body was then repeatedly shot. No one was ever convicted of her lynching.

In 1906, a young African American man named Ed Johnson was murdered by a lynch mob in his home town of Chattanooga, Tennessee. He had been sentenced to death for the rape of Nevada Taylor, but Justice John Marshall Harlan of the United States Supreme Court had issued a stay of execution. To prevent delay or avoidance of execution, a mob broke into the jail where Johnson was held and lynched him.

Laura and L. D. Nelson were an African-American mother and son who were lynched on May 25, 1911, near Okemah, Okfuskee County, Oklahoma. They had been seized from their cells in the Okemah county jail the night before by a group of up to 40 white men, reportedly including Charley Guthrie, father of the folk singer Woody Guthrie. The Associated Press reported that Laura was raped. She and L. D. were then hanged from a bridge over the North Canadian River. According to one source, Laura had a baby with her who survived the attack.

Jim McMillan was lynched in Bibb County, Alabama on June 18, 1919.

The Longview race riot was a series of violent incidents in Longview, Texas, between July 10 and July 12, 1919, when whites attacked black areas of town, killed one black man, and burned down several properties, including the houses of a black teacher and a doctor. It was one of the many race riots in 1919 in the United States during what became known as Red Summer, a period after World War I known for numerous riots occurring mostly in urban areas.

Claude Neal was a 23-year-old African-American farmhand who was arrested in Jackson County, Florida, on October 19, 1934, for allegedly raping and killing Lola Cannady, a 19-year-old white woman missing since the preceding night. Circumstantial evidence was collected against him, but nothing directly linked him to the crime. When the news got out about his arrest, white lynch mobs began to form. In order to keep Neal safe, County Sheriff Flake Chambliss moved him between multiple jails, including the county jail at Brewton, Alabama, 100 miles (160 km) away. But a lynch mob of about 100 white men from Jackson County heard where he was, and brought him back to Jackson County.

The lynching of the Walker family took place near Hickman, Fulton County, Kentucky, on October 3, 1908, at the hands of about fifty masked Night Riders. David Walker was a landowner, with a 21 1/2-acre farm. The entire family of seven African Americans, parents, infant in arms, and four children, was reported killed, with the event carried by national newspapers. Governor Augustus E. Willson of Kentucky strongly condemned the murders and promised a reward for information leading to prosecution. No one was ever prosecuted.

The lynching of Marie Thompson of Shepherdsville took place in the early morning on June 15, 1904, in Lebanon Junction, Bullitt County, Kentucky, for her killing of John Irvin, a white landowner. The day before Thompson had attempted to defend her son from being beaten by Irvin in a dispute; he ordered her off the land. As she was walking away from him, he attacked her with a knife and she killed him in self-defense with a razor. She was arrested and put in the county jail.

The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching (ASWPL) was a women's organization founded by Jessie Daniel Ames in Atlanta, Georgia in November 1930, to lobby and campaign against the lynching of African Americans. The group was made up of middle and upper-class white women. While active, the group had "a presence in every county in the South" of the United States. It was loosely organized and only accepted white women as members because they "believed that only white women could influence other white women." Many of the women involved were also members of missionary societies. Along with the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC), the ASWPL had an important effect on popular opinion among whites relating to lynching.

Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America is a 2016 non-fiction book written by Patrick Phillips investigating the 1912 Racial Conflict of Forsyth County, Georgia.

The lynching of Paul Reed and Will Cato occurred in Statesboro, Georgia on August 16, 1904. Five members of a white farm family, the Hodges, had been murdered and their house burned to hide the crime. Paul Reed and Will Cato, who were African-American, were tried and convicted for the murders. Despite militia having been brought in from Savannah to protect them, the two men were taken by a mob from the courthouse immediately after their trials, chained to a tree stump, and burned. In the immediate aftermath, four more African-Americans were shot, three of them dying, and others were flogged.

James Harvey and Joe Jordan were two African American men who were lynched on July 1, 1922 in Liberty County, Georgia, United States. They were seized by a mob of about 50 people while being transported by police from Wayne County, Georgia to a jail in Savannah, Georgia and hanged. Investigations by the NAACP showed that the police involved were complicit in their abduction by the mob. Twenty-two men were later indicted for the lynching, with four convicted.