The Republic of Central Lithuania, commonly known as the Central Lithuania, and the Middle Lithuania, was a short-lived puppet republic of Poland, that existed from 1920 to 1922, without an international recognition. It was founded on 12 October 1920, after Żeligowski's Mutiny, when soldiers of the Polish Army, mainly the 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Infantry Division under Lucjan Żeligowski, fully supported by the Polish air force, cavalry and artillery, attacked Lithuania. It was incorporated into Poland on 18 April 1922.

The Wilno Voivodeship was one of 16 Voivodeships in the Second Polish Republic, with the capital in Wilno. It was created in 1926 and populated predominantly by Poles with notable minorities of Belarusians, Jews and Lithuanians.

The city of Vilnius, now the capital of Lithuania, and its surrounding region has been under various states. The Vilnius Region has been part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania from the Lithuanian state's founding in the late Middle Ages to 1795, i.e. five hundred years. From then, the region was occupied by the Russian Empire until 1915, when the German Empire invaded it. After 1918 and throughout the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, Vilnius was disputed between the Republic of Lithuania and the Second Polish Republic. After the city was seized by the Republic of Central Lithuania with Żeligowski's Mutiny, the city was part of Poland throughout the Interwar period. Regardless, Lithuania claimed Vilnius as its capital. During World War II, the city changed hands many times, and the German occupation resulting in the destruction of Jews in Lithuania. From 1945 to 1990, Vilnius was the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic's capital. From the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Vilnius has been part of Lithuania.

The Polish–Lithuanian War was a conflict between the newly independent Lithuania and Poland in the aftermath of World War I. The conflict was fought primarily in the Vilnius and Suvalkai Region. The conflict was connected to the Polish–Soviet War and was subject to international mediation at the Conference of Ambassadors, later the League of Nations. The war is viewed differently by the respective sides, with Lithuanian historians considering the war as part of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, spanning from spring 1919 to November 1920 and the Polish historians deeming the war as part of the Polish-Soviet War and happening only in September–October 1920.

The city of Vilnius, the capital and largest city of Lithuania, has undergone a diverse history since it was first settled in the Stone Age. Vilnius was the head of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania right until 1795, even during the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. The city has changed hands many times between Imperial and Soviet Russia, Napoleonic France, Imperial and Nazi Germany, Interwar Poland, and Lithuania. It was especially often the site of conflict after the end of World War I and during World War II. It officially became the capital of independent, modern-day Lithuania when the Soviet Union recognized the country's independence in August 1991.

Vilnius Region, also formerly known as Vilna Region, Wilno Region or Polish: Wileńszczyzna, is the territory in present-day Lithuania and Belarus that was originally inhabited by ethnic Baltic tribes and was a part of Lithuania proper, but came under East Slavic and Polish cultural influences over time.

The Constituent Assembly of Lithuania was the first parliament of the independent state of Lithuania to be elected in a direct, democratic, general, secret election. The Assembly assumed its duties on 15 May 1920 and was disbanded on October 1922.

The 1st Lithuanian–Belarusian Division was a volunteer unit of the Polish Army formed around December 1918 and January 1919 during the Polish–Soviet War. It was created out of several dozen smaller units of self-defence forces composed of local volunteers in what is now Lithuania and Belarus, amidst a growing series of territorial disputes between the Second Polish Republic, the Russian SFSR, and several other local provisional governments. The Division took part in several key battles of the war. Around 15-18% of the division were ethnic Lithuanians.

The Krajowcy were a group of mainly Polish-speaking intellectuals from the Vilnius Region who, at the beginning of the 20th century, opposed the division of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth into nation states along ethnic and linguistic lines. The movement was a reaction against growing nationalism in Poland, Lithuania and Belarus. The Krajowcy attempted to maintain their dual self-identification as Polish–Lithuanian rather than just Polish or Lithuanian. The Krajowcy were scattered and few in number and as a result failed to organize a widescale social movement.

The Polish minority in Lithuania, estimated at 183,000 people, according to the Lithuanian census of 2021, or 6.5% of the total population of Lithuania, is the largest ethnic minority in the country and the second largest Polish diaspora group among the post-Soviet states after the one in Belarus. Poles are concentrated in the Vilnius Region. According to Polish and Lithuanian research, they are mostly Slavicized Lithuanians, although Walter C. Clemens mentions a Belarusian origin.

The Lithuanian minority in Poland consists of 8,000 people living chiefly in the Podlaskie Voivodeship, in the north-eastern part of Poland. The Lithuanian embassy in Poland notes that there are about 15,000 people in Poland of Lithuanian ancestry.

The Vilnius Conference or Vilnius National Conference met between September 18, 1917 and September 22, 1917, and began the process of establishing a Lithuanian state based on ethnic identity and language that would be independent of the Russian Empire, Poland, and the German Empire. It elected a twenty-member Council of Lithuania that was entrusted with the mission of declaring and re-establishing an independent Lithuania. The Conference, hoping to express the will of the Lithuanian people, gave legal authority to the Council and its decisions. While the Conference laid the basic guiding principles of Lithuanian independence, it deferred any matters of political structure of the future Lithuania to the Constituent Assembly, which would later be elected in a democratic manner.

Polish–Lithuanian relations date from the 13th century, after the Grand Duchy of Lithuania under Mindaugas acquired some of the territory of Rus' and thus established a border with the then-fragmented Kingdom of Poland. Polish-Lithuanian relations subsequently improved, ultimately leading to a personal union between the two states. From the mid-16th to the late-18th century Poland and Lithuania merged to form the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, a state that was dissolved following their partition by Austria, Prussia and Russia. After the two states regained independence following the First World War, Polish-Lithuanian relations steadily worsened due to rising nationalist sentiments. Competing claims to the Vilnius region led to armed conflict and deteriorating relations in the interwar period. During the Second World War Polish and Lithuanian territories were occupied by both the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, but relations between Poles and Lithuanians remained hostile. Following the end of World War II, both Poland and Lithuania found themselves in the Eastern Bloc, Poland as a Soviet satellite state, Lithuania as a Soviet republic. With the fall of communism relations between the two countries were reestablished.

Żeligowski's Mutiny was a Polish false flag operation led by General Lucjan Żeligowski in October 1920, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuania. Polish Chief of State Józef Piłsudski surreptitiously ordered Żeligowski to carry out the operation, and revealed the truth only several years afterwards. The area was formally annexed by Poland in 1922 and recognized by the Conference of Ambassadors as Polish territory in 1923. The decision was not recognized by Lithuania, which continued to claim Vilnius and the Vilnius Region, and by the Soviet Union.

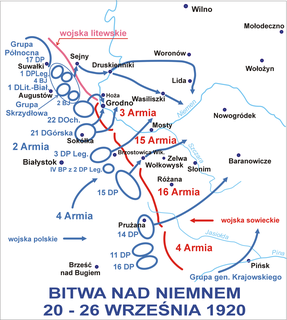

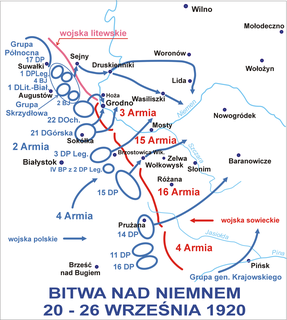

The Suwałki Agreement, Treaty of Suvalkai, or Suwalki Treaty was an agreement signed in the town of Suwałki between Poland and Lithuania on October 7, 1920. It was registered in the League of Nations Treaty Series on January 19, 1922. Both countries had re-established their independence in the aftermath of World War I and did not have well-defined borders. They waged the Polish–Lithuanian War over territorial disputes in the Suwałki and Vilnius Regions. At the end of September 1920, Polish forces defeated the Soviets at the Battle of the Niemen River, thus militarily securing the Suwałki Region and opening the possibility of an assault on the city of Vilnius (Wilno). Polish Chief of State, Józef Piłsudski, had planned to take over the city since mid-September in a false flag operation known as Żeligowski's Mutiny.

The 1926 Lithuanian coup d'état was a military coup d'état in Lithuania that resulted in the replacement of the democratically elected government with a Roman Catholic fascist regime led by Antanas Smetona. The coup took place on 17 December 1926 and was largely organized by the military; Smetona's role remains the subject of debate. The coup brought the Lithuanian Nationalist Union, the most conservative party at the time, to power. Before 1926, it had been a fairly new and insignificant nationalistic party: in 1926, its membership numbered about 2,000 and it had won only three seats in the parliamentary elections. The Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, the largest party in the Seimas at the time, collaborated with the military and provided constitutional legitimacy to the coup, but did not accept any major posts in the new government and withdrew in May 1927. After the military handed power over to the civilian government, it ceased playing a direct role in political life.

The 1925 concordat (agreement) between the Holy See and the Second Polish Republic had 27 articles, which guaranteed the freedom of the Church and the faithful. It regulated the usual points of interests, Catholic instruction in primary schools and secondary schools, nomination of bishops, establishment of seminaries, a permanent nuncio in Warsaw, who also represents the interests of the Holy See in Gdańsk. It was considered one of the most favorable concordats for the Holy See, and would become a basis for many future concordats.

Jakub Wygodzki was a Polish–Lithuanian Jewish politician, Zionist activist and a medical doctor. He was one of the most prominent Jewish activists in Vilnius. Educated as a doctor in Russia and Western Europe, he established his gynecology and pediatric practice in 1884. In 1905, he was one of the founding members of the Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) in Vilnius Region. In 1918, he was co-opted to the Council of Lithuania and briefly served as the first Lithuanian Minister for Jewish Affairs. After Vilnius was captured by Poland, Wygodzki was elected to the Polish parliament (Sejm) in 1922 and 1928. He died in the Lukiškės Prison during the first months of the German occupation of Lithuania during World War II.

Tverečius is a town in Ignalina district municipality, in Utena County, eastern Lithuania. According to the 2011 census, the town has a population of 231 people.

The Battle of Sejny took place in September 1920 during the Polish–Soviet War and Polish–Lithuanian War. Polish Army forces commanded by Edward Śmigły-Rydz and Stefan Dąb-Biernacki, clashed with Lithuanian units near the towns of Sejny and Suwałki.