The Polish United Workers' Party, commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other legally permitted subordinate minor parties together as the Front of National Unity and later Patriotic Movement for National Rebirth. Ideologically, it was based on the theories of Marxism-Leninism, with a strong emphasis on left-wing nationalism. The Polish United Workers' Party had total control over public institutions in the country as well as the Polish People's Army, the UB and SB security agencies, the Citizens' Militia (MO) police force and the media.

Edward Gierek was a Polish Communist politician and de facto leader of Poland between 1970 and 1980. Gierek replaced Władysław Gomułka as First Secretary of the ruling Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR) in the Polish People's Republic in 1970. He is known for opening communist Poland to the Western Bloc and for his economic policies based on foreign loans. He was removed from power after labor strikes led to the Gdańsk Agreement between the communist state and workers of the emerging Solidarity free trade union movement.

Świdnik is a town in southeastern Poland with 40,186 inhabitants (2012), situated in the Lublin Voivodeship, 10 kilometres southeast of the city of Lublin. It is the capital of Świdnik County. Świdnik belongs to the historic province of Lesser Poland, and was first mentioned in historical records in the year 1392. It remained a village until the end of the 19th century when it began to develop as a spa, due to its location and climate.

The 1970 Polish protests occurred in northern Poland during 14–19 December 1970. The protests were sparked by a sudden increase in the prices of food and other everyday items. Strikes were put down by the Polish People's Army and the Citizen's Militia, resulting in at least 44 people killed and more than 1,000 wounded.

The history of Poland from 1945 to 1989 spans the period of Marxist–Leninist regime in Poland after the end of World War II. These years, while featuring general industrialization, urbanization and many improvements in the standard of living, were marred by early Stalinist repressions, social unrest, political strife and severe economic difficulties. Near the end of World War II, the advancing Soviet Red Army, along with the Polish Armed Forces in the East, pushed out the Nazi German forces from occupied Poland. In February 1945, the Yalta Conference sanctioned the formation of a provisional government of Poland from a compromise coalition, until postwar elections. Joseph Stalin, the leader of the Soviet Union, manipulated the implementation of that ruling. A practically communist-controlled Provisional Government of National Unity was formed in Warsaw by ignoring the Polish government-in-exile based in London since 1940.

The Gdańsk Agreement was an accord reached between the government of the Polish People's Republic and the striking shipyard workers in Gdańsk, Poland. The accord, signed in late August 1980 by government representative Mieczysław Jagielski and strike leader Lech Wałęsa, led to the creation of the trade union Solidarity and was an important milestone in the end of Communist rule in Poland.

Martial law in Poland existed between 13 December 1981 and 22 July 1983. The government of the Polish People's Republic drastically restricted everyday life by introducing martial law and a military junta in an attempt to counter political opposition, in particular the Solidarity movement.

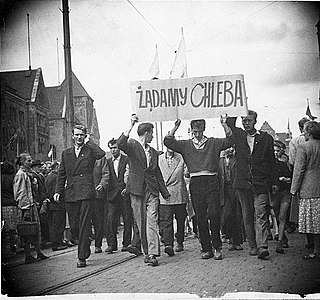

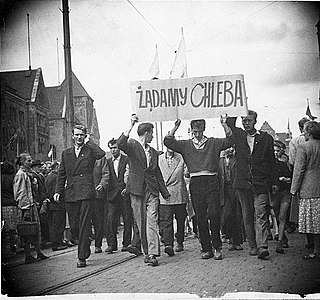

The 1956 Poznań protests, also known as Poznań June, were the first of several massive protests against the communist government of the Polish People's Republic. Demonstrations by workers demanding better working conditions began on 28 June 1956 at Poznań's Cegielski Factories and were met with violent repression.

Solidarity, a Polish non-governmental trade union, was founded on August 14, 1980, at the Lenin Shipyards by Lech Wałęsa and others. In the early 1980s, it became the first independent labor union in a Soviet-bloc country. Solidarity gave rise to a broad, non-violent, anti-Communist social movement that, at its height, claimed some 9.4 million members. It is considered to have contributed greatly to the Fall of Communism.

The June 1976 protests were a series of protests and demonstrations in the Polish People's Republic that took place after Prime Minister Piotr Jaroszewicz revealed the plan for a sudden increase in the price of many basic commodities, particularly food. Prices in Poland were at that time fixed, and controlled by the government, which was falling into increasing debt.

Ursus SA is a Polish agricultural machinery manufacturer, headquartered in Lublin, Poland. The company was founded in Warsaw in 1893, and has strong historic roots regarding Polish tractor production history. It has also carried out some production of trolleybuses in a joint venture with the Ukrainian manufacturer Bogdan, and manufactures buses, coaches, and trolleybuses in a joint venture with AMZ Kutno under the name Ursus Bus.

In the early spring of 1981 in Poland, during the Bydgoszcz events, several members of the Solidarity movement, including Jan Rulewski, Mariusz Łabentowicz and Roman Bartoszcze, were brutally beaten by the security services, such as Milicja Obywatelska and ZOMO. The Bydgoszcz events soon became widely known across Poland, and on 24 March 1981 Solidarity decided to go on a nationwide strike in protest against the violence. The strike was planned for Tuesday, 31 March 1981. On 25 March, Lech Wałęsa met Deputy Prime Minister Mieczysław Rakowski of the Polish United Workers' Party, but their talks were fruitless. Two days later, a four-hour national warning strike took place. It was the biggest strike in the history of not only Poland but of the Warsaw Pact itself. According to several sources, between 12 million and 14 million Poles took part.

Rural Solidarity is a trade union of Polish farmers, established in late 1980 as part of the growing Solidarity movement. Its legalization became possible on February 19, 1981, when officials of the government of the People's Republic of Poland signed the so-called Rzeszów - Ustrzyki Dolne Agreement with striking farmers. Previously, Communist government had refused farmers’ right to self-organize, which caused widespread strikes, with the biggest wave taking place in January 1981. The Rural Solidarity was officially recognized on May 12, 1981, and, strongly backed by the Catholic Church of Poland, it claimed to represent at least half of Poland's 3.2 million smallholders.

The 1988 Polish strikes were a massive wave of workers' strikes which broke out from 21 April 1988 in the Polish People's Republic. The strikes, as well as street demonstrations, continued throughout spring and summer, ending in early September 1988. These actions shook the Communist regime of the country to such an extent that it was forced to begin talking about recognising Solidarity. As a result, later that year, the regime decided to negotiate with the opposition, which opened way for the 1989 Round Table Agreement. The second, much bigger wave of strikes surprised both the government, and top leaders of Solidarity, who were not expecting actions of such intensity. These strikes were mostly organized by local activists, who had no idea that their leaders from Warsaw had already started secret negotiations with the Communists.

Lublin Airport is an airport in Poland serving Lublin and the surrounding region. The site is located about 10 km (6.2 miles) east of central Lublin, adjacent to the town of Świdnik. The airport has a 2520 × m runway (8,270 × 200 ft), and the terminal facilities are capable of handling four Boeing 737-800 class aircraft simultaneously. Construction began in the fall of 2010 and the official opening took place on December 17, 2012. The new airport replaced the grass airstrip, which had served the PZL-Świdnik helicopter factory, and was known as Świdnik Airport with the ICAO identifier EPSW.

On February 10, 1971, textile workers in the central Polish city of Łódź began a strike action, in which the majority of participants were women. These events have been largely forgotten because a few weeks earlier, major protests and street fights had taken place in the cities of northern Poland. Nevertheless, the women of Łódź achieved what shipyard workers of the Baltic Sea coast failed to achieve - cancellation of the increase in food prices, which had been introduced by the government of Communist Poland in December 1970. Consequently, it was the only industrial action in pre-1980 Communist Poland that ended as a success.

The Upper Silesia 1980 strikes were widespread strikes, which took place mostly in the Upper Silesian mining cities Jastrzębie-Zdrój, Wodzisław Śląski and Ruda Śląska and its surroundings, during late August and early September 1980. They forced the Government of People's Republic of Poland to sign the last of three agreements establishing the Solidarity trade union. Earlier, agreements had been signed in Gdańsk and Szczecin. The Jastrzębie Agreement, signed on September 3, 1980, ended Saturday and Sunday work for miners, a concession that Government leaders later said cut deeply into Poland's export earnings.