Santiago del Estero, also known simply as Santiago, is a province in the north of Argentina. Neighboring provinces, clockwise from the north, are Salta, Chaco, Santa Fe, Córdoba, Catamarca and Tucumán.

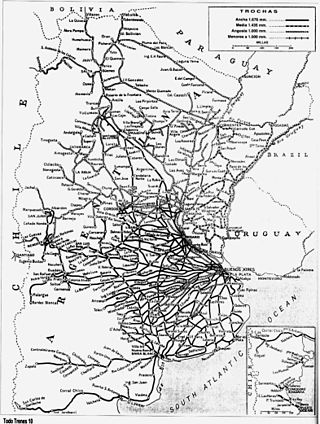

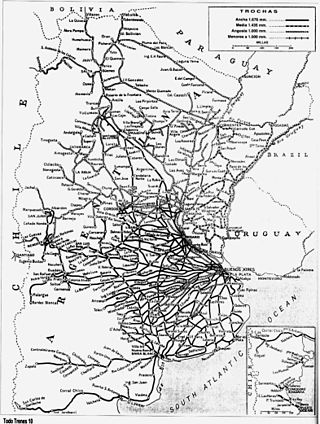

The Argentine railway network consisted of a 47,000 km (29,204 mi) network at the end of the Second World War and was, in its time, one of the most extensive and prosperous in the world. However, with the increase in highway construction, there followed a sharp decline in railway profitability, leading to the break-up in 1993 of Ferrocarriles Argentinos (FA), the state railroad corporation. During the period following privatisation, private and provincial railway companies were created and resurrected some of the major passenger routes that FA once operated.

The 17A protests were a series of massive demonstrations in Argentina which took place on August 17, 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, for several causes, among which: the defense of institutions and separation of powers, against a justice reform announced by the government, against the way quarantine was handled, the lack of liberty, the increase in theft, and a raise on state pensions.

The 18A was an Argentine cacerolazo that took place on April 18, 2013. Attended by nearly two million people, it was the largest demonstration at the time against the president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.

8N was the name given to a massive anti-Kirchnerism protest in several cities in Argentina, including Buenos Aires, Córdoba, Rosario, Mendoza, Olivos, among many others throughout Greater Buenos Aires and other regions; on 8 November 2012. There were also protests in Argentine embassies and consulates in cities such as New York, Miami, Madrid, Sydney, Bogotá, Santiago de Chile, Naples, Zurich and Barcelona, among others. The protest was considered not only a call to Kirchnerism, but also to the opposition, because they did not have a strong leader.

Córdoba is a province of Argentina, located in the center of the country. Its neighboring provinces are Santiago del Estero, Santa Fe, Buenos Aires, La Pampa, San Luis, La Rioja, and Catamarca. Together with Santa Fe and Entre Ríos, the province is part of the economic and political association known as the Center Region.

Operadora Ferroviaria Sociedad del Estado (SOFSE), trading as Trenes Argentinos Operaciones, is an Argentine state-owned company created in 2008 to operate passenger services in Argentina. It operates as a division of Ferrocarriles Argentinos S.E..

A series of massive demonstrations and severe riots, known in Chile as the Estallido Social, originated in Santiago and took place in all regions of Chile, with a greater impact in the regional capitals. The protests mainly occurred between October 2019 and March 2020, in response to a raise in the Santiago Metro's subway fare, a probity crisis, cost of living, university graduate unemployment, privatisation, and inequality prevalent in the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina is part of the worldwide pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. As of 30 November 2024, a total of 10,108,453 people were confirmed to have been infected, and 130,704 people were known to have died because of the virus.

Luis Armando Espinoza, a 31-year-old Argentinian citizen, died during a police raid in the northern province of Tucumán, Argentina, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown in the country.

The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina affected the human rights situation in the country.

Kolina is a Kirchnerist political party in Argentina founded in 2010 by Alicia Kirchner, sister of former president of Argentina, Néstor Kirchner. The party now forms part of Unión por la Patria, the former ruling coalition supporting then-President Alberto Fernández. At the time of its foundation and until the alliance's dissolution, the party was a member of the Front for Victory.

This article presents official statistics gathered during the COVID-19 pandemic in Argentina. The National Ministry of Health publishes official numbers every night.

Luis Alberto Otárola Peñaranda is a Peruvian attorney and politician who was the Prime Minister of Peru from 2022 until his resignation in 2024. He previously served as Minister of Defense twice, under Ollanta Humala and Dina Boluarte.

Following the ousting of president of Peru, Pedro Castillo on 7 December 2022, a series of political protests against the government of president Dina Boluarte and the Congress of Peru occurred. The demonstrations lack centralized leadership and originated primarily among grassroots movements and social organizations on the left to far-left, as well as indigenous communities, who feel politically disenfranchised. Castillo was removed from office and arrested after announcing the illegal dissolution of Congress, the intervention of the state apparatus, and the forced establishment of an "emergency government", which was characterized as a self-coup attempt by all government institutions, all professional institutions, and mainstream media in Peru while Castillo's supporters said that Congress attempted to overthrow Castillo. Castillo's successor Dina Boluarte, along with Congress, were widely disapproved, with the two receiving the lowest approval ratings among public offices in the Americas. Among the main demands of the demonstrators are the dissolution of Congress, the resignation of Boluarte, new general elections, the release of Castillo, and the formation of a constituent assembly to draft a new constitution. It has also been reported that some of the protesters have declared an insurgency in Punos's region. Analysts, businesses, and voters said that immediate elections are necessary to prevent future unrest, although many establishment political parties have little public support.

The 2022–2023 Apurímac protests corresponds to a series of protests and violent confrontations that began on 10 December 2022 in the department of Apurímac in the context of the December 2022 Peruvian protests. The protesters demand the resignation of President Dina Boluarte, the closure of the Congress of the Republic, and new general elections. Unlike the protests in other regions and cities, in Apurímac the confrontations are more violent, and criminal acts have been recorded, such as the kidnapping of police officers and attacks on police stations. The Boluarte government declared a state of emergency, removing some constitutional protections from citizens, including the rights preventing troops from staying within private homes and buildings, freedom of movement, freedom of assembly and "personal freedom and security".

The Ayacucho massacre was a massacre perpetrated by the Peruvian Army on 15 December 2022 in Ayacucho, Peru during the 2022–2023 Peruvian protests, occurring one day after President Dina Boluarte, with the support of right-wing parties in Congress, granted the Peruvian Armed Forces expanded powers and the ability to respond to demonstrations. The clash occurred due to the protesters' attempt to storm the local airport. On that day, demonstrations took place in Ayacucho and the situation intensified when the military deployed helicopters to fire at protesters, who later tried to take over the city's airport, which was defended by the Peruvian Army and the National Police of Peru. Troops responded by firing live ammunition at protesters, resulting in ten dead and 61 injured. Among the injured, 90% had gunshot wounds, while those killed were shot in the head or torso. Nine of the ten killed had wounds consistent with the ammunition used in the IMI Galil service rifle used by the army.

The Juliaca massacre occurred on January 9, 2023, in the city of Juliaca, located in Peru’s Puno Department, amid widespread protests against President Dina Boluarte's government. The event marked one of the deadliest confrontations during the 2022–2023 Peruvian political protests, which erupted following the ousting and imprisonment of former president Pedro Castillo. Peruvian National Police opened fire on demonstrators, who were primarily from the Aymara and Quechua Indigenous communities, resulting in the deaths of at least 18 civilians, including a medical worker, and injuries to over 100 individuals. Most fatalities were caused by gunshot wounds, with reports indicating the use of military-grade weapons by police, sparking widespread condemnation.