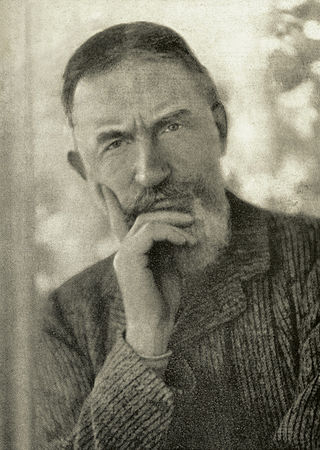

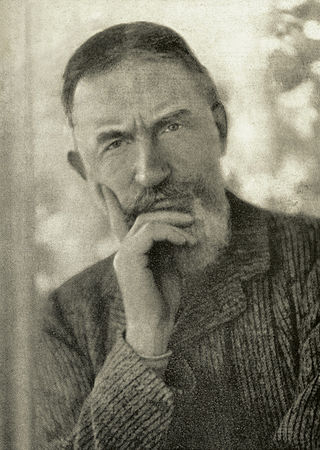

George Bernard Shaw, known at his insistence as Bernard Shaw, was an Irish playwright, critic, polemicist and political activist. His influence on Western theatre, culture and politics extended from the 1880s to his death and beyond. He wrote more than sixty plays, including major works such as Man and Superman (1902), Pygmalion (1913) and Saint Joan (1923). With a range incorporating both contemporary satire and historical allegory, Shaw became the leading dramatist of his generation, and in 1925 was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

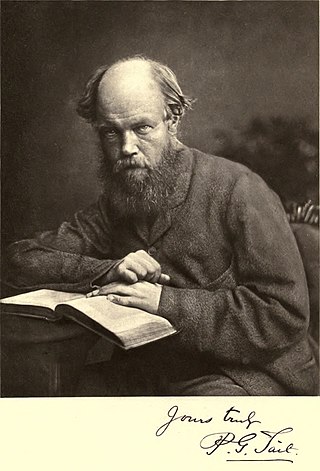

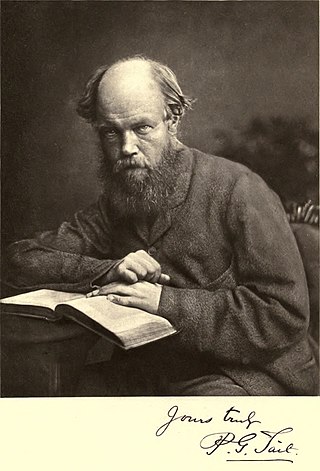

Peter Guthrie Tait was a Scottish mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook Treatise on Natural Philosophy, which he co-wrote with Lord Kelvin, and his early investigations into knot theory.

Patrick Fraser Tytler FRSE FSA(Scot) was a Scottish advocate and historian. He was described as the "Episcopalian historian of a Presbyterian country".

Sir Almroth Edward Wright was a British bacteriologist and immunologist.

Tait is a Scottish surname which means 'pleasure' or 'delight'. The origins of the name can be traced back as far as 1100.

The Penn State University Press, also known as The Pennsylvania State University Press, is a non-profit publisher of scholarly books and journals. Established in 1956, it is the independent publishing branch of the Pennsylvania State University and is a division of the Penn State University Library system.

Time and Tide was a British weekly political and literary review magazine founded by Margaret, Lady Rhondda, in 1920. It started out as a supporter of left wing and feminist causes and the mouthpiece of the feminist Six Point Group. It later moved to the right along with the views of its owner. It always supported and published literary talent.

George Young (1692–1757) was an Edinburgh surgeon, physician, philosopher and empiric. As a young man he was a member of the Rankenian Club, a group of intellectuals who were to go on to become some of the most influential figures of the Scottish Enlightenment. Young's lecture notes (1730–31) give a clear account of contemporary medical and surgical practice and are characterised by the empirical approach to the advancement of medical knowledge, especially in the evolving understanding of nerve and muscle function. His Treatise on Opium (1753) was a practical guide for physicians in the use of the drug which emphasises its complications. It was the longest, most balanced and most comprehensive English language account yet written. Young's legacy is also apparent in the work of his pupil Robert Whytt (1714–1766) and his surgical apprentice James Hill (1703–1776). Young had taught both the value of repeated observation and a sceptical approach to prevailing dogma. Whytt was to advance knowledge of nerve and muscle function while Hill went on to make important contributions to the understanding and management of head injury.

Douglas James Guthrie FRSE FRCS FRCP FRCSEd FRCPE was a Scottish medical doctor, otolaryngologist and historian of medicine.

David Geraint James FRCP was a Welsh physician who devoted his career to the treatment of sarcoidosis, setting up a specialist clinic for the condition and earning the nickname "King of Sarcoid".

The British Society for the History of Medicine (BSHM) is an umbrella organisation of History of medicine societies throughout the United Kingdom, with particular representation to the International Society for the History of Medicine. It has grown from the original four affiliated societies in 1965; the Section for the History of Medicine, The Royal Society of Medicine, London, Osler Club of London, Faculty of the History of Medicine and Pharmacy and the Scottish Society of the History of Medicine, to twenty affiliated societies in 2018.

The Scottish Society of the History of Medicine (SSHM) was founded in 1948. Its aims are "to promote, encourage and support the study of the history of medicine", with a particular interest in Scottish Medicine. Founded at a time when the study of history of medicine was dominated by medical doctors, the society aimed, from the start, to have a broad based membership, to interest others in the subject. Historians, librarians, scientists, pharmacists and others have all played an active role in its activities, and representatives from these professions have become presidents.

The Edinburgh College of Medicine for Women was established by Elsie Inglis and her father John Inglis. Elsie Inglis went on to become a leader in the suffrage movement and found the Scottish Women's Hospital organisation in World War I, but when she jointly founded the college she was still a medical student. Her father, John Inglis, had been a senior civil servant in India, where he had championed the cause of education for women. On his return to Edinburgh he became a supporter of medical education for women and used his influence to help establish the college. The college was founded in 1889 at a time when women were not admitted to university medical schools in the UK.

Haldane Philp Tait (1911-1990) was the Principal Medical Officer for the Child Health Service, Edinburgh and co-founder of the Scottish Society of the History of Medicine and as a result of his contributions, became its President in 1977 and Honorary President in 1981. He also published Dr Elsie Maud Inglis (1864-1917): a great lady doctor in 1964, and later recorded the history of the Edinburgh Health Department from 1862 to 1974 in a book entitled A Doctor and Two Policemen.

Edwin Sisterton Clarke FRCP was a British neurologist and medical historian, best remembered for his role as Director of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, when he succeeded Noël Poynter and oversaw the transfer of the Wellcome museum to the Science museum, helped establish an intercalated BSc degree in the history of medicine for medical students and edited the journal Medical History.

Frederick Noël Lawrence Poynter FLA was a British librarian and medical historian who served as director of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine from 1964 to 1973.

Iain Macintyre FRS was a British endocrinologist who made important contributions to the understanding of calcium regulation and bone metabolism. Shortly after the hormone calcitonin had been described by Harold Copp, Macintyre's team was the first to isolate and sequence the hormone and to demonstrate its origin in the parafollicular cells of the thyroid gland. He subsequently analysed its physiological actions. Along with H. R. Morris he isolated and sequenced calcitonin gene-related peptide. Later research centred on the role played by nitric oxide on bone metabolism.

Extramural medical education in Edinburgh began over 200 years before the university medical faculty was founded in 1726 and extramural teaching continued thereafter for a further 200 years. Extramural is academic education which is conducted outside a university. In the early 16th century it was under the auspices of the Incorporation of Surgeons of Edinburgh (RCSEd) and continued after the Faculty of Medicine was established by the University of Edinburgh in 1726. Throughout the late 18th and 19th centuries the demand for extramural medical teaching increased as Edinburgh's reputation as a centre for medical education grew. Instruction was carried out by individual teachers, by groups of teachers and, by the end of the 19th century, by private medical schools in the city. Together these comprised the Edinburgh Extramural School of Medicine. From 1896 many of the schools were incorporated into the Medical School of the Royal Colleges of Edinburgh under the aegis of the RCSEd and the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (RCPE) and based at Surgeons' Hall. Extramural undergraduate medical education in Edinburgh stopped in 1948 with the closure of the Royal Colleges' Medical School following the Goodenough Report which recommended that all undergraduate medical education in the UK should be carried out by universities.