Related Research Articles

James Shirley was an English dramatist.

Grim the Collier of Croyden; or, The Devil and his Dame: with the Devil and Saint Dunston is a seventeenth-century play of uncertain authorship, first published in 1662. The play's title character is an established figure of the popular culture and folklore of the time who appeared in songs and stories – a body of lore the play draws upon. The London coal and charcoal industry was centred on Croydon, to the south of London in Surrey; the original Grimme or Grimes has been claimed to be a real individual, but evidence for this is not forthcoming.

A devil is a fictional classification of monsters in the Dungeons & Dragons roleplaying game. Often used as a high-level challenge for players of the game, devils are Lawful Evil in alignment and originate from the Nine Hells of Baator. In accordance with their Lawful Evil alignment, devils adhere to a rigid and ruthless hierarchy, undergoing transformations as they ascend the power structure. At the pinnacle of this hierarchy stand the mighty Archdevils, also known as the Lords of the Nine, who exercise dominion over distinct realms within Baator. Devils frequently view the myriad worlds in the D&D metacosmos as instruments to be manipulated for their own purposes, including waging the Blood War—a centuries-long conflict against their arch-foes, the demons.

Robert Davenport was an English dramatist of the early seventeenth century. Nothing is known of his early life or education; the title pages of two of his plays identify him as a "Gentleman," though there is no record of him at either of the two universities or the Inns of Court. Scholars have guessed that he was born c. 1590; if, as some scholars think, he wrote the Address "To the knowing Reader" in the first quarto of King John and Matilda, he was still alive in 1655. He enters the historical record in 1624, when two of his plays were licensed by the Master of the Revels.

Belfagor arcidiavolo is a novella by Niccolò Machiavelli, written between 1518 and 1527, and first published with his collected works in 1549. The novella is also known as La favola di Belfagor Arcidiavolo and Il demonio che prese moglie. Machiavelli's tale appeared in an abbreviated version published by Giovanni Brevio in 1545. Giovanni Francesco Straparola included his own version as the fourth story of the second night in his Le piacevoli notti (1557).

The City Madam is a Caroline era comedy written by Philip Massinger. It was licensed by Sir Henry Herbert, the Master of the Revels, on 25 May 1632 and was acted by the King's Men at the Blackfriars Theatre. It was printed in quarto in 1658 by the stationer Andrew Pennycuicke, who identified himself as "one of the Actors" in the play. A second edition followed in 1659. Pennycuicke dedicated the play to Ann, Countess of Oxford—or at least most of the surviving copies bear a dedication to her; but others are dedicated to any one of four other individuals.

A Mad World, My Masters is a Jacobean stage play written by Thomas Middleton, a comedy first performed around 1605 and first published in 1608. The title had been used by a pamphleteer, Nicholas Breton, in 1603, and was later the origin for the title of Stanley Kramer's 1963 film, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

A Trick to Catch the Old One is a Jacobean comedy written by Thomas Middleton, first published in 1608. The play is a satire in the subgenre of city comedy.

The Devil Is an Ass is a Jacobean comedy by Ben Jonson, first performed in 1616 and first published in 1631.

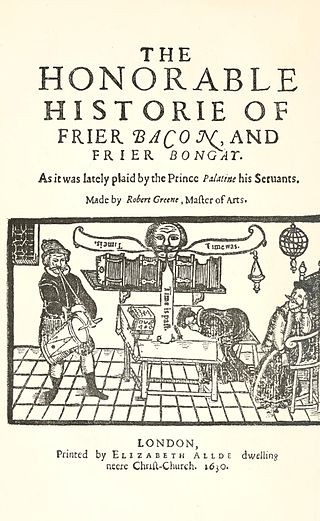

Friar Bacon and Friar Bungay, originally entitled The Honorable Historie of Frier Bacon and Frier Bongay, is an Elizabethan era stage play, a comedy written by Robert Greene. Widely regarded as Greene's best and most significant play, it has received more critical attention than any other of Greene's dramas.

The Devil's Law Case is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by John Webster, and first published in 1623.

A Mad Couple Well-Match'd is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Richard Brome. It was first published in the 1653 Brome collection Five New Plays, issued by the booksellers Humphrey Moseley, Richard Marriot, and Thomas Dring.

The Parson's Wedding is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Thomas Killigrew. Often regarded as the author's best play, the drama has sometimes been considered an anticipation of Restoration comedy, written a generation before the Restoration; "its general tone foreshadows the comedy of the Restoration from which the play is in many respects indistinguishable."

The World Tossed at Tennis is a Jacobean era masque composed by Thomas Middleton and William Rowley, first published in 1620. It was likely acted on 4 March 1620 at Denmark House.

The City Nightcap, or Crede Quod Habes, et Habes is a Jacobean era stage play, a tragicomedy written by Robert Davenport. It is one of only three dramatic works by Davenport that survive.

A Fine Companion is a Caroline era stage play, a comedy written by Shackerley Marmion that was first printed in 1633. It is one of only three surviving plays by Marmion.

Hell is a fictional location, an infernal Underworld utilized in various American comic book stories published by DC Comics. It is the locational antithesis of the Silver City in Heaven. The DC Comics location known as Hell is heavily based on its depiction in Abrahamic mythology. Although several versions of Hell had briefly appeared in other DC Comics publications in the past, the official DC Comics concept of Hell was first properly established when it was mentioned in The Saga of the Swamp Thing #25–27 and was first seen in Swamp Thing Annual #2 (1985), all of which were written by Alan Moore and illustrated by Stephen Bissette and John Totleben.

Mrs. Anne Turner, aka Mistress Anne Turner, was the widow of a respectable London doctor who was hanged at Tyburn for her role in the famous 1613 poisoning of Sir Thomas Overbury referenced in the plays A New Trick to Cheat the Devil, The Widow, The World Tossed at Tennis and The City Nightcap.

A Trilogia das Barcas is a series of one-act dramatic plays with allegorical characters by Portuguese playwright and poet Gil Vicente. Specialists classify them as morality plays even though they resemble more closely farces. They give a glimpse of the Lisboan society in the early 16th century.

Hester Davenport was a leading actress with the Duke's Company under the management of Sir William Davenant. Among the earliest English actresses, she was best known as "that faire & famous Comoedian call'd Roxalana," as diarist John Evelyn put it after seeing her on 9 January 1661/2. Her career ended when she married Aubrey de Vere, 20th Earl of Oxford (1627-1703) in 1662 or 1663. The couple had a son in 1664. Oxford soon deserted Davenport and his son Aubrey, marrying a fellow nobleman's daughter in January 1672. In a 1686 church court case, Oxford admitted the marriage ceremony with Davenport had been a sham.

References

- ↑ A. H. Bullen, ed., The Works of Robert Davenport, Old English Plays, New Series, London 1890; reprinted New York, Benjamin Blom, 1968.

- ↑ Felix Emmanuel Schelling, Elizabethan Drama 1558–1642, 2 Volumes, Boston, Houghton Mifflin, 1908; Vol. 2, pp. 259–61.

- ↑ Bullen, p. xii.

- ↑ Alan R. Young, The English Prodigal Son Plays: A Theatrical Fashion of the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, Salzburg, Austria, Institut fur Anglistik und Amerikanistik, University of Salzburg, 1979.

- ↑ John D. Cox, The Devil and the Sacred in English Drama, 1350–1642, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- ↑ Jan Frans van Dijkhuizen, Devil Theatre: Demonic Possession and Exorcism in English Renaissance Drama, Rochester, NY, D. S. Brewer, 2007.

- ↑ W. J. Olive, "Shakespeare Parody in Davenport's A New Tricke to Cheat the Divell," Modern Language Notes Vol. 66 (1951), pp. 478–80.