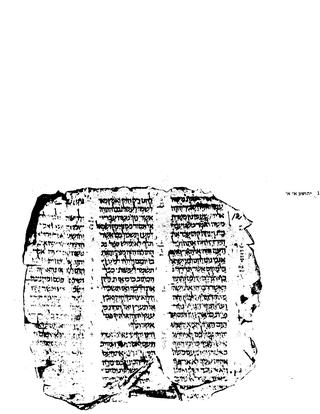

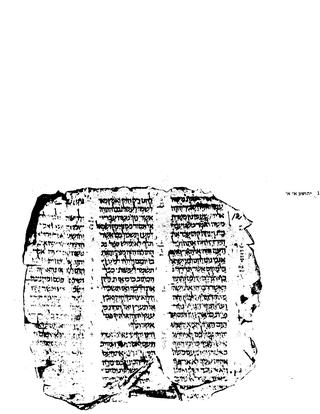

The Masoretic Text is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) in Rabbinic Judaism. The Masoretic Text defines the Jewish canon and its precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas'sora. Referring to the Masoretic Text, masorah specifically means the diacritic markings of the text of the Jewish scriptures and the concise marginal notes in manuscripts of the Tanakh which note textual details, usually about the precise spelling of words. It was primarily copied, edited, and distributed by a group of Jews known as the Masoretes between the 7th and 10th centuries of the Common Era (CE). The oldest known complete copy, the Leningrad Codex, dates from the early 11th century CE.

The Masoretes were groups of Jewish scribe-scholars who worked from around the end of the 5th through 10th centuries CE, based primarily in medieval Palestine in the cities of Tiberias and Jerusalem, as well as in Iraq (Babylonia). Each group compiled a system of pronunciation and grammatical guides in the form of diacritical notes (niqqud) on the external form of the biblical text in an attempt to standardize the pronunciation, paragraph and verse divisions, and cantillation of the Hebrew Bible for the worldwide Jewish community.

The Aleppo Codex is a medieval bound manuscript of the Hebrew Bible. The codex was written in the city of Tiberias in the tenth century CE under the rule of the Abbasid Caliphate, and was endorsed for its accuracy by Maimonides. Together with the Leningrad Codex, it contains the Aaron ben Moses ben Asher Masoretic Text tradition.

Karaite Judaism or Karaism is a Jewish religious movement characterized by the recognition of the written Tanakh alone as its supreme authority in halakha and theology. Karaites believe that all of the divine commandments which were handed down to Moses by God were recorded in the written Torah without any additional Oral Law or explanation. Unlike mainstream Rabbinic Judaism, which regards the Oral Torah, codified in the Talmud and subsequent works, as authoritative interpretations of the Torah, Karaite Jews do not treat the written collections of the oral tradition in the Midrash or the Talmud as binding.

Tiberian Hebrew is the canonical pronunciation of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) committed to writing by Masoretic scholars living in the Jewish community of Tiberias in ancient Galilee c. 750–950 CE under the Abbasid Caliphate. They wrote in the form of Tiberian vocalization, which employed diacritics added to the Hebrew letters: vowel signs and consonant diacritics (nequdot) and the so-called accents. These together with the marginal notes masora magna and masora parva make up the Tiberian apparatus.

The Leningrad Codex is the oldest complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible in Hebrew, using the Masoretic Text and Tiberian vocalization. According to its colophon, it was made in Cairo in AD 1008.

A Mikraot Gedolot, often called the "Rabbinic Bible" in English, is an edition of the Hebrew Bible that generally includes three distinct elements:

Christian David Ginsburg was a Polish-born British Bible scholar and a student of the Masoretic tradition in Judaism. He was born to a Jewish family in Warsaw but converted to Christianity at the age of 15.

Meir ben Todros HaLevi Abulafia, also known as the Ramah, was a major Sephardic Talmudist and Halachic authority in medieval Spain.

The Codex Cairensis is a Hebrew manuscript containing the complete text of the Hebrew Bible's Nevi'im (Prophets). It has traditionally been described as "the oldest dated Hebrew Codex of the Bible which has come down to us", but modern research seems to indicate an 11th-century date rather than the 895 CE date written into its colophon. It contains the books of the Former Prophets and Latter Prophets. It comprises 575 pages including 13 carpet pages.

Ben Naphtali was a rabbi and Masorete who flourished around 890-940 CE, probably in Tiberias. Of his life little is known.

Jewish printers were quick to take advantages of the printing press in publishing the Hebrew Bible. While for synagogue services written scrolls were used, the printing press was very soon called into service to provide copies of the Hebrew Bible for private use. All the editions published before the Complutensian Polyglot were edited by Jews; but afterwards, and because of the increased interest excited in the Bible by the Reformation, the work was taken up by Christian scholars and printers; and the editions published by Jews after this time were largely influenced by these Christian publications. It is not possible in the present article to enumerate all the editions, whole or partial, of the Hebrew text. This account is devoted mainly to the incunabula.

The Jerusalem Crown is a printed edition of the Tanakh printed in Jerusalem in 2001, and based on a manuscript commonly known as the Aleppo Crown). The printed text consists of 874 pages of the Hebrew Bible, two pages setting forth both appearances of the Ten Commandments each showing the two different cantillations—for private and for public recitation, 23 pages briefly describing the research background and listing alternative readings, a page of the blessings—the Ashkenazic, Sephardic and Yemenite versions—used before and after reading the Haftarah, a 9-page list of the annual schedule of the Haftarot readings according to the three traditions.

Seligman (Isaac) Baer (1825–1897) was a Masoretic scholar, and an editor of the Hebrew Bible and of the Jewish liturgy. He was born in Mosbach, the northern district of Biebrich, on 18 September 1825 and died at Biebrich-on-the-Rhine in March 1897.

Biblical grammarians were linguists whose understanding of the Bible at least partially related to the science of Hebrew language. Tannaitic and Ammoraic exegesis rarely toiled in grammatical problems; grammar was a borrowed science from the Arab world in the medieval period. Despite its foreign influence, however, Hebrew grammar was a strongly Jewish product and developed independently. Scholars have continued to study grammar throughout the ages, until the present. Those mentioned in this article are a few of the most eminent grammarians.

The Damascus Pentateuch or Codex Sassoon 507 is a 10th-century Hebrew Bible codex, consisting of the almost complete Pentateuch, the Five Books of Moses. The codex was copied by an unknown scribe, replete with Masoretic annotations. The beginning of the manuscript is damaged: it starts with Genesis 9:26, and Exodus 18:1–23 is also missing. In 1975 it was acquired by the Jewish National and University Library, Jerusalem. The codex was published in a large, two-volume facsimile edition in 1978.

Yemenite scrolls of the Law containing the Five Books of Moses represent one of three authoritative scribal traditions for the transmission of the Torah, the other two being the Ashkenazi and Sephardic traditions that slightly differ. While all three traditions purport to follow the Masoretic traditions of Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, slight differences between the three major traditions have developed over the years. Biblical texts proofread by ben Asher survive in two extant codices, the latter said to have only been patterned after texts proofread by Ben Asher. The former work, although more precise, was partially lost following its removal from Aleppo in 1947.

The Constantinopolitan Karaites or Greco-Karaites are a Karaite community with a specific historical development and a distinct cultural, linguistic, and literary heritage stemming from their residency in the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire. There are numerous commonalities between the community and the Rabbinical Romaniote Jews.

Codex S1 is a Masoretic codex comprising all 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, dated to the 10th century CE. It is considered as old as the Aleppo Codex and a century older than the Leningrad Codex, the earliest known complete Hebrew Bible manuscript. Alternatively, it might be dated to the late 9th century. The Aleppo Codex was missing 40% of its leaves when it resurfaced in Israel in 1958, while in Codex S1 only twelve leaves are completely missing and hundreds more are partially lost. The scribe of S1 was unusually sloppy, frequently forgetting punctuation, diacritical marks, and vowels; he also errs in his consonantal spelling on dozens of occasions.