English Renaissance theatre, also known as Renaissance English theatre and Elizabethan theatre, refers to the theatre of England between 1558 and 1642.

Benjamin Jonson was an English playwright and poet. Jonson's artistry exerted a lasting influence on English poetry and stage comedy. He popularised the comedy of humours; he is best known for the satirical plays Every Man in His Humour (1598), Volpone, or The Fox, The Alchemist (1610) and Bartholomew Fair (1614) and for his lyric and epigrammatic poetry. He is regarded as "the second most important English dramatist, after William Shakespeare, during the reign of James I."

The masque was a form of festive courtly entertainment that flourished in 16th- and early 17th-century Europe, though it was developed earlier in Italy, in forms including the intermedio. A masque involved music, dancing, singing and acting, within an elaborate stage design, in which the architectural framing and costumes might be designed by a renowned architect, to present a deferential allegory flattering to the patron. Professional actors and musicians were hired for the speaking and singing parts. Masquers who did not speak or sing were often courtiers: the English queen Anne of Denmark frequently danced with her ladies in masques between 1603 and 1611, and Henry VIII and Charles I of England performed in the masques at their courts. In the tradition of masque, Louis XIV of France danced in ballets at Versailles with music by Jean-Baptiste Lully.

The Master of the Revels was the holder of a position within the English, and later the British, royal household, heading the "Revels Office" or "Office of the Revels". The Master of the Revels was an executive officer under the Lord Chamberlain. Originally he was responsible for overseeing royal festivities, known as revels, and he later also became responsible for stage censorship, until this function was transferred to the Lord Chamberlain in 1624. However, Henry Herbert, the deputy Master of the Revels and later the Master, continued to perform the function on behalf of the Lord Chamberlain until the English Civil War in 1642, when stage plays were prohibited. The office continued almost until the end of the 18th century, although with rather reduced status.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1613.

The English Renaissance was a cultural and artistic movement in England during the late 15th, 16th and early 17th centuries. It is associated with the pan-European Renaissance that is usually regarded as beginning in Italy in the late 14th century. As in most of the rest of Northern Europe, England saw little of these developments until more than a century later within the Northern Renaissance. Renaissance style and ideas were slow to penetrate England, and the Elizabethan era in the second half of the 16th century is usually regarded as the height of the English Renaissance. Many scholars see its beginnings in the early 16th century during the reign of Henry VIII. Others argue the Renaissance was already present in England in the late 15th century.

John Fletcher was an English playwright. Following William Shakespeare as house playwright for the King's Men, he was among the most prolific and influential dramatists of his day; during his lifetime and in the Stuart Restoration, his fame rivalled Shakespeare's. Fletcher collaborated in writing plays, chiefly with Francis Beaumont or Philip Massinger, but also with Shakespeare and others.

David Martin Bevington was an American literary scholar. He was the Phyllis Fay Horton Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus in the Humanities and in English Language & Literature, Comparative Literature, and the college at the University of Chicago, where he taught since 1967, as well as chair of Theatre and Performance Studies. "One of the most learned and devoted of Shakespeareans," so called by Harold Bloom, he specialized in British drama of the Renaissance, and edited and introduced the complete works of William Shakespeare in both the 29-volume, Bantam Classics paperback editions and the single-volume Longman edition. After accomplishing this feat, Bevington was often cited as the only living scholar to have personally edited Shakespeare's complete corpus.

Frederick Samuel Boas, was an English scholar of early modern drama.

The Masque of Beauty was a courtly masque written by Ben Jonson, and performed in London's Whitehall Palace on 10 January 1608. It inaugurated the refurbished banquesting hall of the palace. It was a sequel to the preceding Masque of Blackness, which had been performed three years earlier, on 6 January 1605. In The Masque of Beauty, the "daughters of Niger" of the earlier piece were shown cleansed of the black pigment they had worn on the prior occasion.

The Triumph of Peace was a Caroline era masque, "invented and written" by James Shirley, performed on 3 February 1634 and published the same year. The production was designed by Inigo Jones.

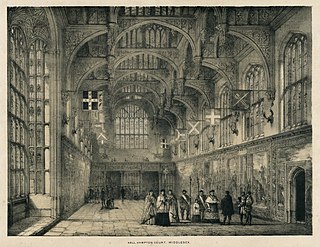

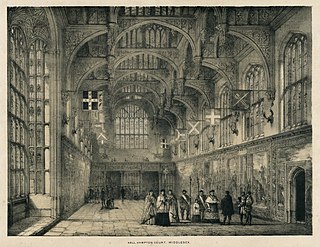

The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses was an early Jacobean-era masque, written by Samuel Daniel and performed in the Great Hall of Hampton Court Palace on the evening of Sunday, 8 January 1604. One of the earliest of the Stuart Court masques, staged when the new dynasty had been in power less than a year and was closely engaged in peace negotiations with Spain, The Vision of the Twelve Goddesses stood as a precedent and a pattern for the many masques that followed during the next four decades.

The Tempest is a play by William Shakespeare, probably written in 1610–1611, and thought to be one of the last plays that he wrote alone. After the first scene, which takes place on a ship at sea during a tempest, the rest of the story is set on a remote island, where Prospero, a complex and contradictory character, lives with his daughter Miranda, and his two servants: Caliban, a savage monster figure, and Ariel, an airy spirit. The play contains music and songs that evoke the spirit of enchantment on the island. It explores many themes, including magic, betrayal, revenge, and family. In Act IV, a wedding masque serves as a play-within-a-play, and contributes spectacle, allegory, and elevated language.

Fulgens and Lucrece is a late 15th-century interlude by Henry Medwall. It is the earliest purely secular English play that survives. Since John Cardinal Morton, for whom Medwall wrote the play, died in 1500, the work must have been written before that date. It was probably first performed at Lambeth Palace in 1497, while Cardinal Morton was entertaining ambassadors from Spain and Flanders. The play is based on a Latin novella by Buonaccorso da Montemagno that had been translated into English by John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester and published in 1481 by William Caxton. The play was printed in 1512–1516 by John Rastell, and was later only available as a fragment until a copy showed up in an auction of books from Lord Mostyn's collection in 1919. Henry E. Huntington acquired this copy, and arranged the printing of a facsimile. The play is an example of a dramatised débat.

History is one of the three main genres in Western theatre alongside tragedy and comedy, although it originated, in its modern form, thousands of years later than the other primary genres. For this reason, it is often treated as a subset of tragedy. A play in this genre is known as a history play and is based on a historical narrative, often set in the medieval or early modern past. History emerged as a distinct genre from tragedy in Renaissance England. The best known examples of the genre are the history plays written by William Shakespeare, whose plays still serve to define the genre. History plays also appear elsewhere in British and Western literature, such as Thomas Heywood's Edward IV, Schiller's Mary Stuart or the Dutch play Gijsbrecht van Aemstel.

Literature in early modern Scotland is literature written in Scotland or by Scottish writers between the Renaissance in the early sixteenth century and the beginnings of the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution in mid-eighteenth century. By the beginning of this era Gaelic had been in geographical decline for three centuries and had begun to be a second class language, confined to the Highlands and Islands, but the tradition of Classic Gaelic Poetry survived. Middle Scots became the language of both the nobility and the majority population. The establishment of a printing press in 1507 made it easier to disseminate Scottish literature and was probably aimed at bolstering Scottish national identity.

The revels were a traditional period of merrymaking and entertainment held at the Inns of Court, the professional associations, training centres and residences of barristers in London, England. The revels were held annually from the early 15th to the early 18th centuries and were an extension of a general nationwide period of entertainment running from All Saints' Eve to Candlemas, though in some years they lasted as late as Lent. The inns elected a "prince" to lead the festivities and put on a sequence of elaborate entertainments and wild parties. The events included singing, dancing, feasting, the holding of mock trials and the performance of plays and masques. The revels played an important part in encouraging early English theatre and provided William Shakespeare with one of his most distinguished audiences in his early career. Several plays were written specifically for the revels and legal scenes in many plays from this era may have been written with this audience in mind. The revels declined in the 17th century and they last appear to have been held in 1733. The inns revived the revels in the mid 20th-century and they now comprise a seasonal offering of entertainment in the form of sketches, songs and jokes.

Enid Elder Hancock Welsford was an English literary scholar, a Fellow of Newnham College, Cambridge, and twice winner of the Rose Mary Crawshay Prize – in 1928 and 1967. She is best known for her book The Fool: his Social and Literary History, published in 1935.

The Masque of Indian and China Knights was performed at Hampton Court in Richmond, England on 1 January 1604. The masque was not published, and no text survives. It was described in a letter written by Dudley Carleton. The historian Leeds Barroll prefers the title, Masque of the Orient Knights.

Marie Axton (1937–2014), birth name Marie Horine, was an American scholar of Elizabethan drama, who made her academic career in the United Kingdom. She married Richard Axton of Christ's College, Cambridge in 1962. In 1979 she became the first woman appointed a junior proctor by the University of Cambridge.