Related Research Articles

Perthshire, officially the County of Perth, is a historic county and registration county in central Scotland. Geographically it extends from Strathmore in the east, to the Pass of Drumochter in the north, Rannoch Moor and Ben Lui in the west, and Aberfoyle in the south; it borders the counties of Inverness-shire and Aberdeenshire to the north, Angus to the east, Fife, Kinross-shire, Clackmannanshire, Stirlingshire and Dunbartonshire to the south and Argyllshire to the west.

Cromartyshire was a county in the Highlands of Scotland, comprising the medieval "old shire" around the county town of Cromarty and 22 enclaves and exclaves transferred from Ross-shire in the late 17th century. The largest part, six times the size of the old shire, was Coigach, containing Ullapool and the area north-west of it. In 1889, Cromartyshire was merged with Ross-shire to become a new county called Ross and Cromarty, which in 1975 was merged into the new council area of Highland.

The Lord President of the Court of Session and Lord Justice General is the most senior judge in Scotland, the head of the judiciary, and the presiding judge of the College of Justice, the Court of Session, and the High Court of Justiciary. The Lord President holds the title of Lord Justice General of Scotland and the head of the High Court of Justiciary ex officio, as the two offices were combined in 1836. The Lord President has authority over any court established under Scots law, except for the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom and the Court of the Lord Lyon.

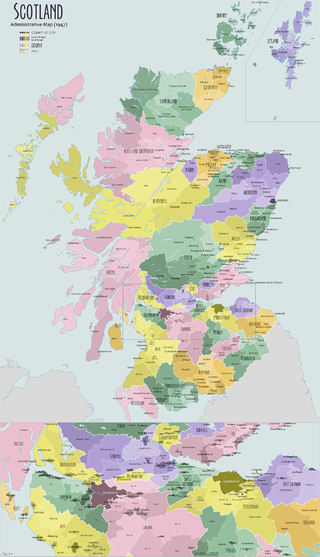

The Shires of Scotland, or Counties of Scotland, were historic subdivisions of Scotland.

Ross and Cromarty, is an area in the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. In modern usage, it is a registration county and a lieutenancy area. Between 1889 and 1975 it was a county.

The High Court of Justiciary is the supreme criminal court in Scotland. The High Court is both a trial court and a court of appeal. As a trial court, the High Court sits on circuit at Parliament House or in the adjacent former Sheriff Court building in the Old Town in Edinburgh, or in dedicated buildings in Glasgow and Aberdeen. The High Court sometimes sits in various smaller towns in Scotland, where it uses the local sheriff court building. As an appeal court, the High Court sits only in Edinburgh. On one occasion the High Court of Justiciary sat outside Scotland, at Zeist in the Netherlands during the Pan Am Flight 103 bombing trial, as the Scottish Court in the Netherlands. At Zeist the High Court sat both as a trial court, and an appeal court for the initial appeal by Abdelbaset al-Megrahi.

A sheriff court is the principal local civil and criminal court in Scotland, with exclusive jurisdiction over all civil cases with a monetary value up to £100,000, and with the jurisdiction to hear any criminal case except treason, murder, and rape, which are in the exclusive jurisdiction of the High Court of Justiciary. Though the sheriff courts have concurrent jurisdiction with the High Court over armed robbery, drug trafficking, and sexual offences involving children, the vast majority of these cases are heard by the High Court. Each court serves a sheriff court district within one of the six sheriffdoms of Scotland. Each sheriff court is presided over by a sheriff, who is a legally qualified judge, and part of the judiciary of Scotland.

In Scotland a sheriff principal is a judge in charge of a sheriffdom with judicial, quasi-judicial, and administrative responsibilities. Sheriffs principal have been part of the judiciary of Scotland since the 11th century. Sheriffs principal were originally appointed by the monarch of Scotland, and evolved into a heritable jurisdiction before appointment was again vested in the Crown and the monarch of the United Kingdom following the passage of the Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746.

The Church of Scotland was one of the first national churches to accept the ordination of women. In Presbyterianism, ordination is understood to be an ordinance rather than a sacrament; ministers and elders are ordained; until recently deacons were "commissioned" but now they too are ordained to their office in the Church of Scotland.

A sheriffdom is a judicial district in Scotland, led by a sheriff principal. Since 1 January 1975, there have been six sheriffdoms. Each sheriffdom is divided into a series of sheriff court districts, and each sheriff court is presided over by a resident or floating sheriff. Sheriffs principal and resident or floating sheriffs are all members of the judiciary of Scotland.

Holders of the office of Lord Chamberlain of Scotland are known from about 1124. It was ranked by King Malcolm as the third great Officer of State, called Camerarius Domini Regis, and had a salary of £200 per annum allotted to him. He anciently collected the revenues of the Crown, at least before Scotland had a Treasurer, of which office there is no vestige until the restoration of King James I when he disbursed the money necessary for the maintenance of the King's Household.

The Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746 or the Sheriffs Act 1747 was an act of Parliament passed in the aftermath of the Jacobite rising of 1745 abolishing judicial rights held by Scots heritors. These were a significant source of power, especially for clan chiefs since it gave them a large measure of control over their tenants.

In the Courts of Scotland, a sheriff-substitute was the historical name for the judges who sit in the local sheriff courts under the direction of the sheriffs principal; from 1971 the sheriffs substitute were renamed simply as sheriff. When researching the history of the sheriffs and sheriffs principal of Scotland there is much confusion over the use of different names to refer to sheriffs in Scotland. Sheriffs principal are those sheriffs who have held office over a sheriffdom, whether through inheritance or through direct appointment by the Crown. Thus, hereditary sheriff and sheriff-depute are the precursors to the modern office of sheriff principal.

The judiciary of Scotland are the judicial office holders who sit in the courts of Scotland and make decisions in both civil and criminal cases. Judges make sure that cases and verdicts are within the parameters set by Scots law, and they must hand down appropriate judgments and sentences. Judicial independence is guaranteed in law, with a legal duty on Scottish Ministers, the Lord Advocate and the Members of the Scottish Parliament to uphold judicial independence, and barring them from influencing the judges through any form of special access.

The Sheriff of Edinburgh was historically the royal official responsible for enforcing law and order and bringing criminals to justice in the shire of Edinburgh in Scotland. In 1482 the burgh of Edinburgh itself was given the right to appoint its own sheriff, and thereafter the sheriff of Edinburgh's authority applied in the area of Midlothian outside the city, whilst still being called the sheriff of Edinburgh. Prior to 1748 most sheriffdoms were held on a hereditary basis. From that date, following the Jacobite uprising of 1745, they were replaced by salaried sheriff-deputes, qualified advocates who were members of the Scottish Bar.

Perth Sheriff Court is an historic building on Tay Street in Perth, Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The structure, which is used as the main courthouse for the area, is a Category A listed building.

County Buildings is a municipal structure in Ettrick Terrace, Selkirk, Scottish Borders, Scotland. The complex, which was the headquarters of Selkirkshire County Council and was also used as a courthouse, is a Category B listed building.

County Offices is a former municipal building on Main Street in Golspie in Scotland. The building, which used to be the headquarters of Sutherland County Council, is now divided into seven residential properties known as 1-7 The Old Post Office.

Dornoch Sheriff Court, also known as County Buildings, is a former judicial building on Castle Street in Dornoch in Scotland. The building, which is now used as a restaurant, is a Category B listed building.

References

- ↑ Burrill. A Law Dictionary and Glossary. 2nd Ed. 1859. vol 1. p 49.

- ↑ Brewer. Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. New Edition. 1895. p 13.

- ↑ Wood. Dictionary of Quotations. 1893. p 4

- ↑ "National Education" in "Monthly Retrospect" (1868) 12 United Presbyterian Magazine (New Series) 96 (February 1868). "The Retirement of Professors in the Scottish Universities" (1895) 2 British Medical Journal 1386 at 1387 (30 November 1895). Stevenson, Fulfilling a Vision, Pickwick Publications, 2012, p 132.

- ↑ Robertson and others v Keillor (1864) 3 Sheriff Court Reports (New Series) 108; Trustees of the Woodside Institution v Keillor (1865) 4 Session Cases 9, Scots Revised Reports (Macpherson IV) 68; Murray v Morton (1878) 6 Session Cases (Fourth Series) 26 at 30.

- ↑ "National Education" (1867) 4 Museum and English Journal of Education 138. Bell, "Alexander Monro primus and the ad vitam aut culpam principle" (1965) 10 Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons Edinburgh 324. John McGowan, Policing the Metropolis of Scotland, 2nd Ed, Turlough Publishers, 2012, p 62.

- ↑ For sources that speak of "ad vitam aut culpam appointment(s)", see for example Irons, The Burgh Police (Scotland) Act, 1892, William Green and Sons, 1893, p 135; (1887) 15 Poor Law Magazine and Parochial Journal 122.

- ↑ Bradley and Christie. The Scotland Act 1978. W Green & Son. 1979. p 51/54. (1913) 13 The Nation 17 (5 April 1913).

- ↑ Watson. Bell's Dictionary and Digest of the Law of Scotland. 7th Ed. 1890. p 26. See further pages 79, 603, 1007 and 1131.

- ↑ The Statutes: Second Revised Edition, 1889, vol 2, p 208

- ↑ The Statutes: Second Revised Edition, 1889, vol 2, p 300

- ↑ Heritable Jurisdictions (Scotland) Act 1746 "Stewart v. Secretary of State for Scotland". Office of Public Sector Information. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007.

- ↑ Hay Shennan. "Ad vitam aut culpam". Green's Encyclopaedia of the Law of Scotland. 1896. vol 1. p 140.

- ↑ Hay Shennan. "Ad vitam aut culpam". Green's Encyclopaedia of the Law of Scotland. vol 1. p 140.

- ↑ Hay Shennan. "Ad vitam aut culpam". Green's Encyclopaedia of the Law of Scotland. vol 1. p 141.

- ↑ Hay Shennan. "Ad vitam aut culpam". Green's Encyclopaedia of the Law of Scotland. vol 1. p 141.

- ↑ Hay Shennan. "Ad vitam aut culpam". Green's Encyclopaedia of the Law of Scotland. vol 1. p 141.

- ↑ Hay Shennan. "Ad vitam aut culpam". Green's Encyclopaedia of the Law of Scotland. vol 1. p 141.