Related Research Articles

The Cardinal of the Kremlin is an espionage thriller novel, written by Tom Clancy and released on May 20, 1988. A direct sequel to The Hunt for Red October (1984), it features CIA analyst Jack Ryan as he extracts CARDINAL, the agency's highest placed agent in the Soviet government who is being pursued by the KGB, as well as the Soviet intelligence agency's director. The novel also features the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), a real-life missile-defense system developed by the United States during that time, and its Russian counterpart. The book debuted at number one on the New York Times bestseller list.

Cold War espionage describes the intelligence gathering activities during the Cold War between the Western allies and the Eastern Bloc. Both relied on a wide variety of military and civilian agencies in this pursuit.

Robert Philip Hanssen was an American Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) agent who spied for Soviet and Russian intelligence services against the United States from 1979 to 2001. His espionage was described by the Department of Justice as "possibly the worst intelligence disaster in U.S. history".

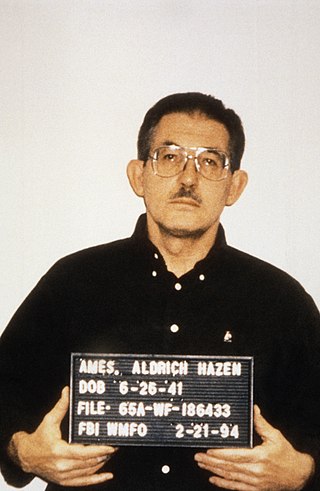

Aldrich Hazen Ames is an American former CIA counterintelligence officer who was convicted of espionage on behalf of the Soviet Union and Russia in 1994. He is serving a life sentence, without the possibility of parole, in the Federal Correctional Institution in Terre Haute, Indiana. Ames was known to have compromised more highly classified CIA assets than any other officer until Robert Hanssen, who was arrested seven years later in 2001.

Oleg Antonovich Gordievsky, CMG is a former colonel of the KGB who became KGB resident-designate (rezident) and bureau chief in London.

Oleg Vladimirovich Penkovsky, codenamed Hero and Yoga was a Soviet military intelligence (GRU) colonel during the late 1950s and early 1960s. Penkovsky informed the United States and the United Kingdom about Soviet military secrets, including the appearance and footprint of Soviet intermediate-range ballistic missile installations and the weakness of the Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program. This information was decisive in allowing the US to recognize that the Soviets were placing missiles in Cuba before most of them were operational. It also gave US President John F. Kennedy, during the Cuban Missile Crisis that followed, valuable information about Soviet weakness that allowed him to face down Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev and resolve the crisis without a nuclear war.

Yuri Vasilevich Krotkov was a Soviet dramatist. Working as a KGB agent, he (allegedly) defected to the West in 1963.

As early as the 1920s, the Soviet Union, through its GRU, OGPU, NKVD, and KGB intelligence agencies, used Russian and foreign-born nationals, as well as Communists of American origin, to perform espionage activities in the United States, forming various spy rings. Particularly during the 1940s, some of these espionage networks had contact with various U.S. government agencies. These Soviet espionage networks illegally transmitted confidential information to Moscow, such as information on the development of the atomic bomb. Soviet spies also participated in propaganda and disinformation operations, known as active measures, and attempted to sabotage diplomatic relationships between the U.S. and its allies.

George Kisevalter was an American operations officer of the CIA, who handled Major Pyotr Popov, the first Soviet GRU officer run by the CIA. He had some involvement with Soviet intelligence Colonel Oleg Penkovsky, active in the 1960s, who had more direct relations with British MI-6.

Yuri Ivanovich Nosenko was a putative KGB officer who ostensibly defected to the United States in 1964. Controversy arose as to whether or not he was a KGB "plant," and he was held in detention by the CIA for over three years. Eventually, he was deemed a true defector. After his release he became an American citizen and worked as a consultant and lecturer for the CIA.

Dmitri Fyodorovich Polyakov was a Major General in the Soviet GRU during the Cold War. According to former high-level KGB officer Sergey Kondrashev, Polyakov acted as a KGB disinformation agent at the FBI's New York City field office when he was posted at United Nations headquarters in 1962. Kondrashev's post-Cold War friend, former high-level CIA counterintelligence officer Tennent H. Bagley, says Polyakov "flipped" and started spying for the CIA when he was reposted to Rangoon, Moscow, and New Delhi. Polyakov was suddenly recalled to Moscow in 1980, arrested, tried, and finally executed in 1988.

Clandestine HUMINT asset recruiting refers to the recruitment of human agents, commonly known as spies, who work for a foreign government, or within a host country's government or other target of intelligence interest for the gathering of human intelligence. The work of detecting and "doubling" spies who betray their oaths to work on behalf of a foreign intelligence agency is an important part of counterintelligence.

Fedora was the codename for Aleksey Kulak (1923–1983), a KGB-agent who infiltrated the United Nations during the Cold War. One afternoon in March 1962, Kulak walked into the FBI's NYC field office in broad daylight and offered his services. Kulak told his American handlers there was a KGB mole working at the FBI, leading to a decades-long mole hunt that seriously disrupted the agency. Although the FBI's official position for a few years in the late 1970s and early 1980s was that Fedora had been Kremlin-loyal all along, that position was reversed to its original one in the mid-1980s, and Fedora is now said by the Bureau to have been spying faithfully for the FBI from when he "walked in" in March 1962 until he returned to Moscow for good in 1977.

David Emanuel Hoffman is an American writer and journalist, a contributing editor to The Washington Post. He won a Pulitzer Prize in 2010 for a book about the legacy of the nuclear arms race and in 2024 for articles on new technologies and the tactics authoritarian regimes use to repress dissent.

George Sadil is a former Russian analyst and translator who worked with the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) for nearly 25 years including during the height of the Cold War. After it had been revealed the ASIO had been compromised by a Russian KGB 'mole', investigations were held and after internal audits conducted by both ASIO (Jabaroo) and the Australian Federal Police, Sadil was accused of being the mole. After raids on the homes of many of their analysts and translators, the authorities found highly classified documents in Sadil's home, he was then charged with possessing classified federal documents under the Crimes Act 1914. In 1994 the case against him collapsed. Sadil's profile did not match that of the mole in question, and prosecutors were unable to establish any kind of money trail between Sadil and the KGB.

In 1995 it was revealed that the Central Intelligence Agency had delivered intelligence reports to the U.S. government between 1986 and 1994 which were based on agent reporting from confirmed or suspected Soviet operatives. From 1985 to his arrest in February 1994, CIA officer and KGB mole Aldrich Ames compromised Agency sources and operations in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, leading to the arrest of many CIA agents and the execution of at least ten of them. This allowed the KGB to replace the CIA agents with its own operatives or to force them to cooperate, and the double agents then funneled a mixture of disinformation and true material to U.S. intelligence. Although the CIA's Soviet-East European (SE) and Central Eurasian divisions knew or suspected the sources to be Soviet double agents, they nevertheless disseminated this "feed" material within the government. Some of these intelligence reports even reached Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush, as well as President-elect Bill Clinton.

David Henry Blee served in the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) from its founding in 1947 until his 1985 retirement. During World War II in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), he had worked in Southeast Asia. In the CIA, he served as Chief of Station (COS) in Asia and Africa, starting in the 1950s. He then led the CIA's Near East Division.

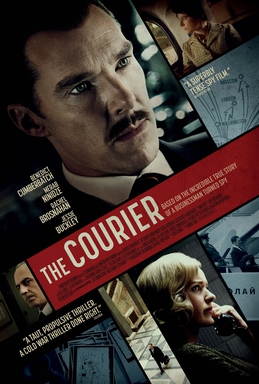

The Courier is a 2020 historical spy film directed by Dominic Cooke and written by Tom O'Connor. The film stars Benedict Cumberbatch as Greville Wynne, and is based on the true story of a British businessman who was recruited by the Secret Intelligence Service to be a message conduit with Russian spy source Oleg Penkovsky in the 1960s. Rachel Brosnahan, Jessie Buckley, and Angus Wright also star.

The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal is a non-fiction history book by David E. Hoffman.

Tennent Harrington Bagley was a high-level CIA counterintelligence officer who worked against the KGB during the Cold War. He is best known for having been the case officer and principal interrogator of controversial KGB defector Yuri Nosenko who claimed a couple of months after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy that the KGB had nothing to do with the accused assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, during the two-and-one-half years Oswald lived in the USSR.

References

- Fischer, Benjamin (2008). "The Spy Who Came in for the Gold: A Skeptical View of the GTVANQUISH Case". Journal of Intelligence History. 8 (1): 29–54. doi:10.1080/16161262.2008.10555148. S2CID 155965016.

- Hoffman, David (2015). The Billion Dollar Spy: A True Story of Cold War Espionage and Betrayal. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-38553760-5.

- Royden, Barry (2003). "Tolkachev, A Worthy Successor to Penkovsky" (PDF). Studies in Intelligence. 47 (3).