Related Research Articles

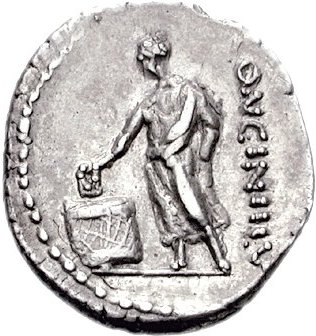

The censor was a magistrate in ancient Rome who was responsible for maintaining the census, supervising public morality, and overseeing certain aspects of the government's finances.

The Solonian constitution was created by Solon in the early 6th century BC. At the time of Solon, the Athenian State was almost falling to pieces in consequence of dissensions between the parties into which the population was divided. Solon wanted to revise or abolish the older laws of Draco. He promulgated a code of laws embracing the whole of public and private life, the salutary effects of which lasted long after the end of his constitution.

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not patricians, as determined by the census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of Roman laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation of alliances. Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the people held the ultimate source of sovereignty.

The equites constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an eques.

Aerarium, from aes + -ārium, was the name given in Ancient Rome to the public treasury, and in a secondary sense to the public finances.

Social class in ancient Rome was hierarchical, with multiple and overlapping social hierarchies. An individual's relative position in one might be higher or lower than in another, which complicated the social composition of Rome.

A tribus, or tribe, was a division of the Roman people for military, censorial, and voting purposes. When constituted in the comitia tributa, the tribes were the voting units of a legislative assembly of the Roman Republic.

The structural history of the Roman military concerns the major transformations in the organization and constitution of ancient Rome's armed forces, "the most effective and long-lived military institution known to history." At the highest level of structure, the forces were split into the Roman army and the Roman navy, although these two branches were less distinct than in many modern national defense forces. Within the top levels of both army and navy, structural changes occurred as a result of both positive military reform and organic structural evolution. These changes can be divided into four distinct phases.

In the early Roman Empire, from 30 BC to AD 212, a peregrinus was a free provincial subject of the Empire who was not a Roman citizen. Peregrini constituted the vast majority of the Empire's inhabitants in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. In AD 212, all free inhabitants of the Empire were granted citizenship by the Constitutio Antoniniana, with the exception of the dediticii, people who had become subject to Rome through surrender in war, and freed slaves.

Ius or Jus in ancient Rome was a right to which a citizen (civis) was entitled by virtue of his citizenship (civitas). The iura were specified by laws, so ius sometimes meant law. As one went to the law courts to sue for one's rights, ius also meant justice and the place where justice was sought.

The socii or foederati were confederates of Rome and formed one of the three legal denominations in Roman Italy (Italia) along with the core Roman citizens and the extended Latini. The Latini, who were simultaneously special confederates and semi-citizens, derived their name from the Italic people of which Rome was part but did not coincide with the region of Latium in central Italy as they were located in colonies throughout the peninsula. This tripartite organisation lasted from the Roman expansion in Italy to the Social War, when all peninsular inhabitants south of the Po river were awarded Roman citizenship.

The Roman Assemblies were institutions in ancient Rome. They functioned as the machinery of the Roman legislative branch, and thus passed all legislation. Since the assemblies operated on the basis of a direct democracy, ordinary citizens, and not elected representatives, would cast all ballots. The assemblies were subject to strong checks on their power by the executive branch and by the Roman Senate. Laws were passed by Curia, Tribes, and century.

The executive magistrates of the Roman Republic were officials of the ancient Roman Republic, elected by the People of Rome. Ordinary magistrates (magistratus) were divided into several ranks according to their role and the power they wielded: censors, consuls, praetors, curule aediles, and finally quaestor. Any magistrate could obstruct (veto) an action that was being taken by a magistrate with an equal or lower degree of magisterial powers. By definition, plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles were technically not magistrates as they were elected only by the plebeians, but no ordinary magistrate could veto any of their actions. Dictator was an extraordinary magistrate normally elected in times of emergency for a short period. During this period, the dictator's power over the Roman government was absolute, as they were not checked by any institution or magistrate.

The history of the Constitution of the Roman Republic is a study of the ancient Roman Republic that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC until the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BC. The constitutional history of the Roman Republic can be divided into five phases. The first phase began with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Kingdom in 509 BC, and the final phase ended with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Republic, and thus created the Roman Empire, in 27 BC. Throughout the history of the Republic, the constitutional evolution was driven by the struggle between the aristocracy and the ordinary citizens.

The Tribal Assembly was an assembly consisting of all Roman citizens convened by tribes (tribus).

The Centuriate Assembly of the Roman Republic was one of the three voting assemblies in the Roman constitution. It was named the Centuriate Assembly as it originally divided Roman citizens into groups of one hundred men by classes. The centuries initially reflected military status, but were later based on the wealth of their members. The centuries gathered into the Centuriate Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The majority of votes in any century decided how that century voted. Each century received one vote, regardless of how many electors each Century held. Once a majority of centuries voted in the same way on a given measure, the voting ended, and the matter was decided. Only the Centuriate Assembly could declare war or elect the highest-ranking Roman magistrates: consuls, praetors and censors. In addition, the Centuriate Assembly served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases, and ratified the results of a Census.

The nationality law of Bangladesh governs the issues of citizenship and nationality of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The law regulates the nationality and citizenship status of all people who live in Bangladesh as well as all people who are of Bangladeshi descent. It allows the children of expatriates, foreigners as well as residents in Bangladesh to examine their citizenship status and if necessary, apply for and obtain citizenship of Bangladesh.

Roman colonies in North Africa are the cities—populated by Roman citizens—created in North Africa by the Roman Empire, mainly in the period between the reigns of Augustus and Trajan.

In Ancient Rome, Tributum was a tax imposed on the citizenry to fund the costs of war. The Tributum was one of the central reasons for the conducting of the census on assets, as it rose with wealth. It included cash assets, land, property and moveable goods. Several types of tributum have been attested to, including tributum in capita, tributum temerarium, and tributum ex censu.

References

- 1 2 3 One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Aerarii". Encyclopædia Britannica . Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 259.