The Roman Republic was a state of the classical Roman civilization, run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom and ending in 27 BC with the establishment of the Roman Empire, Rome's control rapidly expanded during this period—from the city's immediate surroundings to hegemony over the entire Mediterranean world.

The Roman Kingdom was the earliest period of Roman history when the city and its territory were ruled by kings. According to oral accounts, the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding c. 753 BC, with settlements around the Palatine Hill along the river Tiber in central Italy, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic c. 509 BC.

Servius Tullius was the legendary sixth king of Rome, and the second of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned from 578 to 535 BC. Roman and Greek sources describe his servile origins and later marriage to a daughter of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus, Rome's first Etruscan king, who was assassinated in 579 BC. The constitutional basis for his accession is unclear; he is variously described as the first Roman king to accede without election by the Senate, having gained the throne by popular and royal support; and as the first to be elected by the Senate alone, with support of the reigning queen but without recourse to a popular vote.

Tribune was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs acted as a check on the authority of the senate and the annual magistrates, holding the power of ius intercessionis to intervene on behalf of the plebeians, and veto unfavourable legislation. There were also military tribunes, who commanded portions of the Roman army, subordinate to higher magistrates, such as the consuls and praetors, promagistrates, and their legates. Various officers within the Roman army were also known as tribunes. The title was also used for several other positions and classes in the course of Roman history.

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of Roman laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation of alliances. Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the people held the ultimate source of sovereignty.

In ancient Roman religion, the rex sacrorum was a senatorial priesthood reserved for patricians. Although in the historical era, the pontifex maximus was the head of Roman state religion, Festus says that in the ranking of the highest Roman priests, the rex sacrorum was of highest prestige, followed by the flamines maiores and the pontifex maximus. The rex sacrorum was based in the Regia.

The equites constituted the second of the property-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an eques.

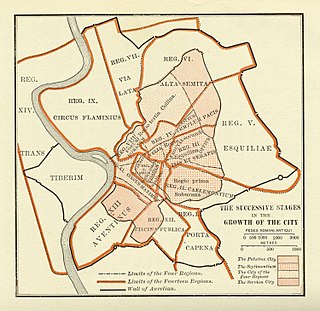

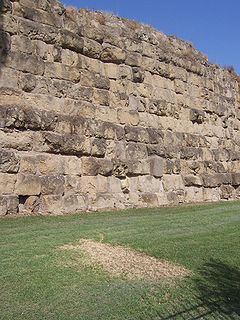

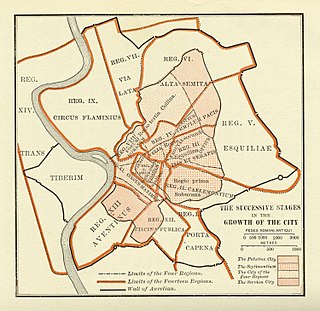

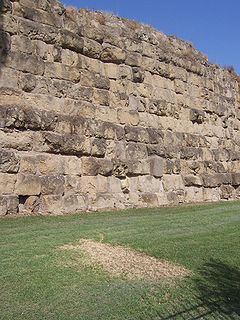

The Servian Wall was an ancient Roman defensive barrier constructed around the city of Rome in the early 4th century BC. The wall was built of volcanic tuff and was up to 10 m (33 ft) in height in places, 3.6 m (12 ft) wide at its base, 11 km (6.8 mi) long, and is believed to have had 16 main gates, of which only one or two have survived, and enclosed a total area of 246 hectares. In the 3rd century AD it was superseded by the construction of the larger Aurelian Walls as the city of Rome grew beyond the boundary of the Servian Wall.

The Concilium Plebis was the principal assembly of the common people of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative/judicial assembly, through which the plebeians (commoners) could pass legislation, elect plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian Council was originally organized on the basis of the Curia but in 471 BC adopted an organizational system based on residential districts or tribes. The Plebeian Council usually met in the well of the Comitium and could only be convoked by the Tribune of the Plebs. The patricians were excluded from the Council.

The Curiate Assembly was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome were organized into thirty units called "Curiae". The Curiae were ethnic in nature, and thus were organized on the basis of the early Roman family, or, more specifically, on the basis of the thirty original patrician (aristocratic) clans. The Curiae formed an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Curiate Assembly passed laws, elected Consuls, and tried judicial cases. Consuls always presided over the assembly. While plebeians (commoners) could participate in this assembly, only the patricians could vote.

A consul held the highest elected political office of the Roman Republic, and ancient Romans considered the consulship the second-highest level of the cursus honorum after that of the censor. Each year, the Centuriate Assembly elected two consuls to serve jointly for a one-year term. The consuls alternated in holding fasces – taking turns leading – each month when both were in Rome and a consul's imperium extended over Rome and all its provinces.

A tribus, or tribe, was a division of the Roman people, constituting the voting units of a legislative assembly of the Roman Republic. The word is probably derived from tribuere, to divide or distribute; the traditional derivation from tres, three, is doubtful.

The constitution of the Roman Republic was a set of uncodified norms and customs which, together with various written laws, guided the procedural governance of the Roman Republic. The constitution emerged from that of the Roman kingdom, evolved substantively and significantly—almost to the point of unrecognisability—over the almost five hundred years of the republic. The collapse of republican government and norms from 133 BC would lead to the rise of Augustus and his principate.

The socii or foederati were confederates of Rome and formed one of the three legal denominations in Roman Italy (Italia) along with the Roman citizens (Cives) and the Latini. The Latini, who were simultaneously special confederates and semi-citizens, should not be equated with the homonymous Italic people of which Rome was part. This tripartite organisation lasted from the Roman expansion in Italy to the Social War, when all peninsular inhabitants were awarded Roman citizenship.

The Roman Assemblies were institutions in ancient Rome. They functioned as the machinery of the Roman legislative branch, and thus passed all legislation. Since the assemblies operated on the basis of a direct democracy, ordinary citizens, and not elected representatives, would cast all ballots. The assemblies were subject to strong checks on their power by the executive branch and by the Roman Senate. Laws were passed by Curia, Tribes, and century.

The Centuriate Assembly of the Roman Republic was one of the three voting assemblies in the Roman constitution. It was named the Centuriate Assembly as it originally divided Roman citizens into groups of one hundred men by classes. The centuries initially reflected military status, but were later based on the wealth of their members. The centuries gathered into the Centuriate Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The majority of votes in any century decided how that century voted. Each century received one vote, regardless of how many electors each Century held. Once a majority of centuries voted in the same way on a given measure, the voting ended, and the matter was decided. Only the Centuriate Assembly could declare war or elect the highest-ranking Roman magistrates: consuls, praetors and censors. The Centuriate Assembly could also pass a law that granted constitutional command authority, or "Imperium", to Consuls and Praetors, and Censorial powers to Censors. In addition, the Centuriate Assembly served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases, and ratified the results of a Census.

The Early Roman army was deployed by ancient Rome during its Regal Era and into the early Republic around 300 BC, when the so-called "Polybian" or manipular legion was introduced.

The lex Publilia, also known as the Publilian Rogation, was a law traditionally passed in 471 BC, transferring the election of the tribunes of the plebs to the comitia tributa, thereby freeing their election from the direct influence of the Senate and patrician magistrates.

The proletariat is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power. A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philosophy considers the proletariat to be exploited under capitalism, forced to accept meager wages in return for operating the means of production, which belong to the class of business owners, the bourgeoisie.

Publilian Laws refers to a set of laws meant to increase the amount of political power the plebeian class held in the Roman Republic. The laws are named for Volero Publilius and Quintus Publilius Philo, the two tribunes responsible for the law's passing.