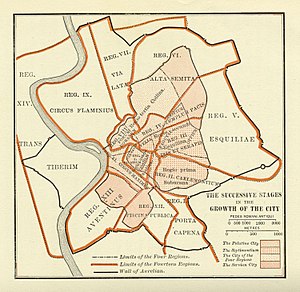

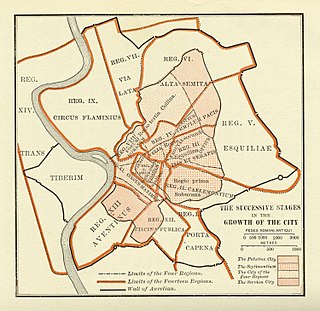

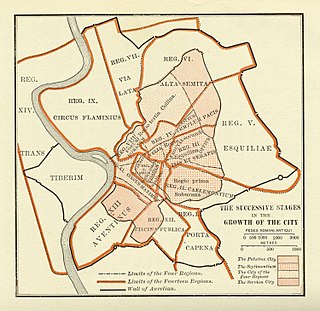

The Roman Kingdom, also referred to as the Roman monarchy or the regal period of ancient Rome, was the earliest period of Roman history when the city and its territory were ruled by kings. According to tradition, the Roman Kingdom began with the city's founding c. 753 BC, with settlements around the Palatine Hill along the river Tiber in central Italy, and ended with the overthrow of the kings and the establishment of the Republic c. 509 BC.

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of Roman laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation of alliances. Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the people held the ultimate source of sovereignty.

The Conflictof the Orders, sometimes referred to as the Struggle of the Orders, was a political struggle between the plebeians (commoners) and patricians (aristocrats) of the ancient Roman Republic lasting from 500 BC to 287 BC in which the plebeians sought political equality with the patricians. It played a major role in the development of the Constitution of the Roman Republic. Shortly after the founding of the Republic, this conflict led to a secession from Rome by the Plebeians to the Sacred Mount at a time of war. The result of this first secession was the creation of the office of plebeian tribune, and with it the first acquisition of real power by the plebeians.

The Concilium Plebis was the principal assembly of the common people of the ancient Roman Republic. It functioned as a legislative/judicial assembly, through which the plebeians (commoners) could pass legislation, elect plebeian tribunes and plebeian aediles, and try judicial cases. The Plebeian Council was originally organized on the basis of the Curia but in 471 BC adopted an organizational system based on residential districts or tribes. The Plebeian Council usually met in the well of the Comitium and could only be convoked by the tribune of the plebs. The patricians were excluded from the Council.

The Curiate Assembly was the principal assembly that evolved in shape and form over the course of the Roman Kingdom until the Comitia Centuriata organized by Servius Tullius. During these first decades, the people of Rome were organized into thirty units called "Curiae". The Curiae were ethnic in nature, and thus were organized on the basis of the early Roman family, or, more specifically, on the basis of the thirty original patrician (aristocratic) clans. The Curiae formed an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Curiate Assembly passed laws, elected Consuls, and tried judicial cases. Consuls always presided over the assembly. While plebeians (commoners) could participate in this assembly, only the patricians could vote.

A tribus, or tribe, was a division of the Roman people for military, censorial, and voting purposes. When constituted in the comitia tributa, the tribes were the voting units of a legislative assembly of the Roman Republic.

The king of Rome was the ruler of the Roman Kingdom. According to legend, the first king of Rome was Romulus, who founded the city in 753 BC upon the Palatine Hill. Seven legendary kings are said to have ruled Rome until 509 BC, when the last king was overthrown. These kings ruled for an average of 35 years.

The Roman magistrates were elected officials in Ancient Rome. During the period of the Roman Kingdom, the King of Rome was the principal executive magistrate. His power, in practice, was absolute. He was the chief priest, lawgiver, judge, and the sole commander of the army. When the king died, his power reverted to the Roman Senate, which then chose an Interrex to facilitate the election of a new king.

The Roman Constitution was an uncodified set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. The Roman constitution was not formal or even official, largely unwritten and constantly evolving. Having those characteristics, it was therefore more like the British and United States common law system than a sovereign law system like the English Constitutions of Clarendon and Great Charter or the United States Constitution, even though the constitution's evolution through the years was often directed by passage of new laws and repeal of older ones.

The Roman Senate was the highest and constituting assembly of ancient Rome and its aristocracy. With different powers throughout its existence it lasted from the first days of the city of Rome as the Senate of the Roman Kingdom, to the Senate of the Roman Republic and Senate of the Roman Empire and eventually the Byzantine Senate of the Eastern Roman Empire, existing well into the post-classical era and Middle Ages.

The Roman Assemblies were institutions in ancient Rome. They functioned as the machinery of the Roman legislative branch, and thus passed all legislation. Since the assemblies operated on the basis of a direct democracy, ordinary citizens, and not elected representatives, would cast all ballots. The assemblies were subject to strong checks on their power by the executive branch and by the Roman Senate. Laws were passed by Curia, Tribes, and century.

The History of the Roman Constitution is a study of Ancient Rome that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the city of Rome in 753 BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in 476 AD. The constitution of the Roman Kingdom vested the sovereign power in the King of Rome. The king did have two rudimentary checks on his authority, which took the form of a board of elders and a popular assembly. The arrangement was similar to the constitutional arrangements found in contemporary Greek city-states. These Greek constitutional principles probably came to Rome through the Greek colonies of Magna Graecia in southern Italy. The Roman Kingdom was overthrown in 510 BC, according to legend, and in its place the Roman Republic was founded.

The Senate of the Roman Kingdom was a political institution in the ancient Roman Kingdom. The word senate derives from the Latin word senex, which means "old man". Therefore, senate literally means "board of old men" and translates as "Council of Elders". The prehistoric Indo-Europeans who settled Rome in the centuries before the legendary founding of Rome in 753 BC were structured into tribal communities. These tribal communities often included an aristocratic board of tribal elders, who were vested with supreme authority over their tribe. The early tribes that had settled along the banks of the Tiber eventually aggregated into a loose confederation, and later formed an alliance for protection against invaders.

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Kingdom were political institutions in the ancient Roman Kingdom. While one assembly, the Curiate Assembly, had some legislative powers, these powers involved nothing more than a right to symbolically ratify decrees issued by the king. The functions of the other assembly, the Calate Assembly, was purely religious. During the years of the kingdom, the People of Rome were organized on the basis of units called curiae. All of the People of Rome were divided amongst a total of thirty curia, and membership in an individual curia was hereditary. Each member of a particular family belonged to the same curia. Each curia had an organization similar to that of the early Roman family, including specific religious rites and common festivals. These curia were the basic units of division in the two popular assemblies. The members in each curia would vote, and the majority in each curia would determine how that curia voted before the assembly. Thus, a majority of the curia was needed during any vote before either the Curiate Assembly or the Calate Assembly.

The executive magistrates of the Roman Kingdom were elected officials of the ancient Roman Kingdom. During the period of the Roman Kingdom, the Roman King was the principal executive magistrate. His power, in practice, was absolute. He was the chief executive, chief priest, chief lawgiver, chief judge, and the sole commander-in-chief of the army. He had the sole power to select his own assistants, and to grant them their powers. Unlike most other ancient monarchs, his powers rested on law and legal precedent, through a type of statutory authorization known as "Imperium". He could only receive these powers through the political process of a democratic election, and could theoretically be removed from office. As such, he could not pass his powers to an heir upon his death, and he typically received no divine honors or recognitions. When the king died, his power reverted to the Roman Senate, which then chose an Interrex to facilitate the election of a new king. The new king was then formally elected by the People of Rome, and, upon the acquiescence of the Roman Senate, he was granted his Imperium by the people through the popular assembly.

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Empire were political institutions in the ancient Roman Empire. During the reign of the second Roman Emperor, Tiberius, the powers that had been held by the Roman assemblies were transferred to the senate. The neutering of the assemblies had become inevitable for reasons beyond the fact that they were composed of the rabble of Rome. The electors were, in general, ignorant as to the merits of the important questions that were laid before them, and often willing to sell their votes to the highest bidder.

The executive magistrates of the Roman Empire were elected individuals of the ancient Roman Empire. During the transition from monarchy to republic, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the executive to the Roman Senate. During the transition from republic to empire, the constitutional balance of power shifted back to the executive. Theoretically, the senate elected each new emperor, although in practice, it was the army which made the choice. The powers of an emperor, existed, in theory at least, by virtue of his legal standing. The two most significant components to an emperor's imperium were the "tribunician powers" and the "proconsular powers". In theory at least, the tribunician powers gave the emperor authority over Rome's civil government, while the proconsular powers gave him authority over the Roman army. While these distinctions were clearly defined during the early empire, eventually they were lost, and the emperor's powers became less constitutional and more monarchical.

The history of the Constitution of the Roman Republic is a study of the ancient Roman Republic that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC until the founding of the Roman Empire in 27 BC. The constitutional history of the Roman Republic can be divided into five phases. The first phase began with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Kingdom in 509 BC, and the final phase ended with the revolution which overthrew the Roman Republic, and thus created the Roman Empire, in 27 BC. Throughout the history of the Republic, the constitutional evolution was driven by the struggle between the aristocracy and the ordinary citizens.

The history of the Constitution of the Roman Kingdom is a study of the ancient Roman Kingdom that traces the progression of Roman political development from the founding of the city of Rome in 753 BC to the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom in 510 BC. The constitution of the Roman Kingdom vested the sovereign power in the King of Rome. The king did have two rudimentary checks on his authority, which took the form of a board of elders and a popular assembly. The arrangement was similar to the constitutional arrangements found in contemporary Greek city-states. These Greek constitutional principles probably came to Rome through the Greek colonies of Magna Graecia in southern Italy. In the centuries before the legendary founding of the city of Rome, Greek settlers had colonized much of the Mediterranean world. These settlers carried Greek ideals with them, and often kept in contact with the Greek mainland. Thus, the superstructure of the Roman constitution was ultimately of Greek origin.

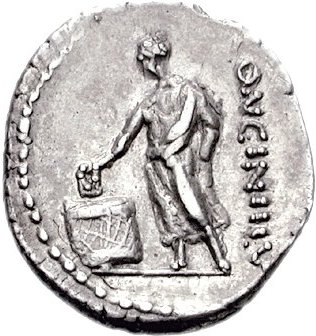

The curio maximus was an obscure priesthood in ancient Rome that had oversight of the curiae, groups of citizens loosely affiliated within what was originally a tribe. Each curia was led by a curio, who was admitted only after the age of 50 and held his office for life. The curiones were required to be in good health and without physical defect, and could not hold any other civil or military office; the pool of willing candidates was thus neither large nor eager. In the early Republic, the curio maximus was always a patrician, and officiated as the senior interrex. The earliest curio maximus identified as such is Servius Sulpicius, who held the office in 463. The first plebeian to hold the office was elected in 209 BC.