Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus, also known as Octavian, was the founder of the Roman Empire. He reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in AD 14. The reign of Augustus initiated an imperial cult, as well as an era of imperial peace in which the Roman world was largely free of armed conflict. The Principate system of government was established during his reign and lasted until the Crisis of the Third Century.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient Rome:

Gallia Lugdunensis was a province of the Roman Empire in what is now the modern country of France, part of the Celtic territory of Gaul formerly known as Celtica. It is named after its capital Lugdunum, possibly Roman Europe's major city west of Italy, and a major imperial mint. Outside Lugdunum was the Sanctuary of the Three Gauls, where representatives met to celebrate the cult of Rome and Augustus.

Praetor, also pretor, was the title granted by the government of ancient Rome to a man acting in one of two official capacities: (i) the commander of an army, and (ii) as an elected magistratus (magistrate), assigned to discharge various duties. The functions of the magistracy, the praetura (praetorship), are described by the adjective itself: the praetoria potestas, the praetorium imperium, and the praetorium ius, the legal precedents established by the praetores (praetors). Praetorium, as a substantive, denoted the location from which the praetor exercised his authority, either the headquarters of his castra, the courthouse (tribunal) of his judiciary, or the city hall of his provincial governorship. The minimum age for holding the praetorship was 39 during the Roman Republic, but it was later changed to 30 in the early Empire.

Gallia Aquitania, also known as Aquitaine or Aquitaine Gaul, was a province of the Roman Empire. It lies in present-day southwest France and the comarca of Val d'Aran in northeast Spain, where it gives its name to the modern region of Aquitaine. It was bordered by the provinces of Gallia Lugdunensis, Gallia Narbonensis, and Hispania Tarraconensis.

In ancient Rome, a promagistrate was a person who was granted the power via prorogation to act in place of an ordinary magistrate in the field. This was normally pro consule or pro praetore, that is, in place of a consul or praetor, respectively. This was an expedient development, starting in 327 BC and becoming regular by 241 BC, that was meant to allow consuls and praetors to continue their activities in the field without disruption.

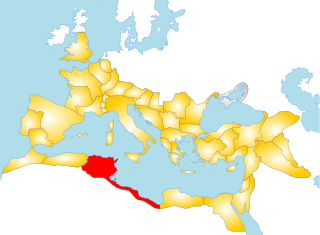

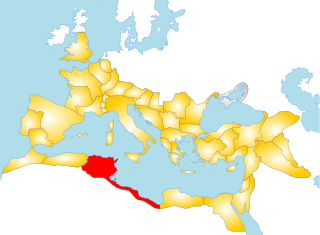

Gallia Narbonensis was a Roman province located in what is now Occitania and Provence, in Southern France. It was also known as Provincia Nostra, because it was the first Roman province north of the Alps, and as Gallia Transalpina, distinguishing it from Cisalpine Gaul in Northern Italy. It became a Roman province in the late 2nd century BC. Gallia Narbonensis was bordered by the Pyrenees Mountains on the west, the Cévennes to the north, the Alps on the east, and the Gulf of Lion on the south; the province included the majority of the Rhone catchment. The western region of Gallia Narbonensis was known as Septimania. The province was a valuable part of the Roman Empire, owing to the Greek colony and later Roman Civitas of Massalia, its location between the Spanish provinces and Rome, and its financial output.

A proconsul was an official of ancient Rome who acted on behalf of a consul. A proconsul was typically a former consul. The term is also used in recent history for officials with delegated authority.

A Roman governor was an official either elected or appointed to be the chief administrator of Roman law throughout one or more of the many provinces constituting the Roman Empire.

This is a historical timeline of Portugal.

Macedonia was a province of ancient Rome, encompassing the territory of the former Antigonid Kingdom of Macedonia, which had been conquered by the Roman Republic in 168 BC at the conclusion of the Third Macedonian War. The province was created in 146 BC, after the Roman general Quintus Caecilius Metellus defeated Andriscus of Macedon, the last self-styled King of Macedonia in the Fourth Macedonian War. The province incorporated the former Kingdom of Macedonia with the addition of Epirus, Thessaly, and parts of Illyria, Paeonia and Thrace.

The Constitution of the Roman Empire was an unwritten set of guidelines and principles passed down mainly through precedent. After the fall of the Roman Republic, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the Roman Senate to the Roman Emperor. Beginning with the first emperor, Augustus, the emperor and the Senate were theoretically two co-equal branches of government. In practice, however, the actual authority of the imperial Senate was negligible, as the emperor held the true power of the state. During the reign of the second emperor, Tiberius, many of the powers that had been held by the Roman assemblies were transferred to the Senate.

The executive magistrates of the Roman Empire were elected individuals of the ancient Roman Empire. During the transition from monarchy to republic, the constitutional balance of power shifted from the executive to the Roman Senate. During the transition from republic to empire, the constitutional balance of power shifted back to the executive. Theoretically, the senate elected each new emperor, although in practice, it was the army which made the choice. The powers of an emperor, existed, in theory at least, by virtue of his legal standing. The two most significant components to an emperor's imperium were the "tribunician powers" and the "proconsular powers". In theory at least, the tribunician powers gave the emperor authority over Rome's civil government, while the proconsular powers gave him authority over the Roman army. While these distinctions were clearly defined during the early empire, eventually they were lost, and the emperor's powers became less constitutional and more monarchical.

The history of the constitution of the Roman Empire begins with the establishment of the Principate in 27 BC and is considered to conclude with the abolition of that constitutional structure in favour of the Dominate at Diocletian's accession in AD 284.

A legatus Augusti pro praetore was the official title of the governor or general of some Imperial provinces of the Roman Empire during the Principate era, normally the larger ones or those where legions were based. Provinces were denoted imperial if their governor was selected by the emperor, in contrast to senatorial provinces, whose governors were elected by the Roman Senate.

Marcus Baebius Tamphilus was a consul of the Roman Republic in 181 BC along with P. Cornelius Cethegus. Baebius is credited with reform legislation pertaining to campaigns for political offices and electoral bribery (ambitus). The Lex Baebia was the first bribery law in Rome and had long-term impact on Roman administrative practices in the provinces.

This section of the timeline of Hispania concerns Spanish and Portuguese history events from the Carthaginian conquests to before the barbarian invasions.

Roman Republican governors of Gaul were assigned to the province of Cisalpine Gaul or to Transalpine Gaul, the Mediterranean region of present-day France also called the Narbonensis, though the latter term is sometimes reserved for a more strictly defined area administered from Narbonne. Latin Gallia can also refer in this period to greater Gaul independent of Roman control, covering the remainder of France, Belgium, and parts of the Netherlands and Switzerland, often distinguished as Gallia Comata and including regions also known as Celtica, Aquitania, Belgica, and Armorica (Brittany). To the Romans, Gallia was a vast and vague geographical entity distinguished by predominately Celtic inhabitants, with "Celticity" a matter of culture as much as speaking gallice.

The Terentii Varrones were a branch of the gens Terentia in ancient Rome.

Tenagino Probus was a Roman soldier and procuratorial official whose career reached its peak at the end of the sixth decade of the third century AD. A poverty of primary sources means that nothing is known for certain of his origins or early career. However, in later years he served successively as Praeses (governor) of the province of Numidia and of Egypt,. These were both very senior procuratorial offices, the latter in particular traditionally considered one of the pinnacles of an equestrian career. In these roles he exercised military skills in addition to administrative ones; as Praefectus Aegypti he led military operations outside his province. He died resisting the invasion of Egypt by the forces of Zenobia of Palmyra in the troubled interregnum between Emperors Claudius II and Aurelian.