Lucius Septimius Severus was a Roman politician who served as emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through the customary succession of offices under the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and Commodus. Severus was the final contender to seize power after the death of the emperor Pertinax in 193 during the Year of the Five Emperors.

Oea was an ancient city in present-day Tripoli, Libya. It was founded by the Phoenicians in the 7th century BC and later became a Roman–Berber colony. As part of the Roman Africa Nova province, Oea and surrounding Tripolitania were prosperous. It reached its height in the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, when the city experienced a golden age under the Severan dynasty in nearby Leptis Magna. The city was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate with the spread of Islam in the 7th century and came to be known as Tripoli during the 9th century.

Africa was a Roman province on the northern coast of the continent of Africa. It was established in 146 BC, following the Roman Republic's conquest of Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of Algeria, and the coast of western Libya along the Gulf of Sidra. The territory was originally and still is inhabited by Berbers, known in Latin as the Mauri, indigenous to all of North Africa west of Egypt. In the 9th century BC, Semitic-speaking Phoenicians from West Asia built settlements along the coast of the Mediterranean Sea to facilitate shipping. Carthage, rising to prominence in the 8th century BC, became the predominant of these.

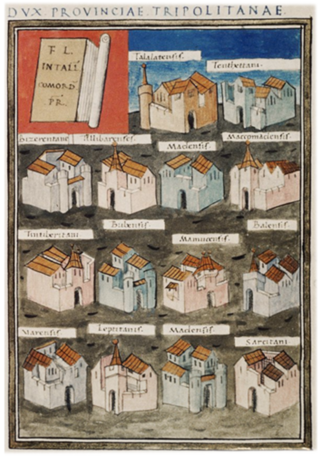

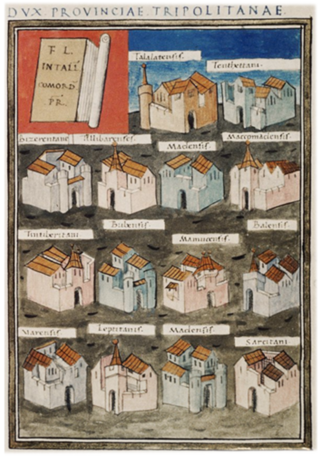

Tripolitania, historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province of Libya.

Sabratha, in the Zawiya District of Libya, was the westernmost of the ancient "three cities" of Roman Tripolis, alongside Oea and Leptis Magna. From 2001 to 2007 it was the capital of the former Sabratha wa Sorman District. It lies on the Mediterranean coast about 70 km (43 mi) west of modern Tripoli. The extant archaeological site was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1982.

Utica was an ancient Phoenician and Carthaginian city located near the outflow of the Medjerda River into the Mediterranean, between Carthage in the south and Hippo Diarrhytus in the north. It is traditionally considered to be the first colony to have been founded by the Phoenicians in North Africa. After Carthage's loss to Rome in the Punic Wars, Utica was an important Roman colony for seven centuries.

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians, were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term Punic, the Latin equivalent of the Greek-derived term Phoenician, is exclusively used to refer to Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean, following the line of the Greek East and Latin West. The largest Punic settlement was Ancient Carthage, but there were 300 other settlements along the North African coast from Leptis Magna in modern Libya to Mogador in southern Morocco, as well as western Sicily, southern Sardinia, the southern and eastern coasts of the Iberian Peninsula, Malta, and Ibiza. Their language, Punic, was a dialect of Phoenician, one of the Northwest Semitic languages originating in the Levant.

Leptis or Lepcis Parva was a Phoenician colony and Carthaginian and Roman port on Africa's Mediterranean coast, corresponding to the modern town Lemta, just south of Monastir, Tunisia. In antiquity, it was one of the wealthiest cities in the region.

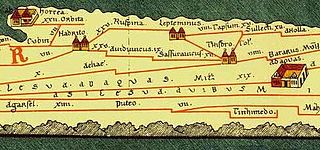

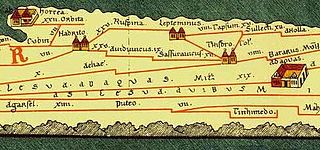

The Limes Tripolitanus was a frontier zone of defence of the Roman Empire, built in the south of what is now Tunisia and the northwest of Libya. It was primarily intended as a protection for the tripolitanian cities of Leptis Magna, Sabratha and Oea in Roman Libya.

Publius Septimius Geta was the father of the emperor Lucius Septimius Severus, father-in-law of the Roman empress Julia Domna and the paternal grandfather of the Roman emperors Caracalla and Geta. Besides mentions in the Historia Augusta, Geta is known from several inscriptions, two of which were found in Leptis Magna, Africa.

Icosium was a Phoenician and Punic settlement in modern-day Algeria. It was part of Numidia and later became an important Roman colony and an early medieval bishopric in the casbah area of modern Algiers.

Tourism in Libya is an industry heavily hit by the Libyan Civil War. Before the war tourism was developing, with 149,000 tourists visiting Libya in 2004, rising to 180,000 in 2007, although this still only contributed less than 1% of the country's GDP. There were 1,000,000 day visitors in the same year. The country is best known for its ancient Greek and Roman ruins and Sahara desert landscapes.

Al-Khums or Khoms is a city, port and the de jure capital of the Murqub District on the Mediterranean coast of Libya with an estimated population of around 202,000. The population at the 1984 census was 38,174. Between 1983 and 1995 it was the administrative center of al-Khums District.

Gerisa, also called Ghirza, was an ancient city of Roman Libya near the Limes Tripolitanus. It was a small village of 300 inhabitants on the pre-desert zone of Tripolitania.

The area of North Africa which has been known as Libya since 1911 was under Roman domination between 146 BC and 672 AD. The Latin name Libya at the time referred to the continent of Africa in general. What is now coastal Libya was known as Tripolitania and Pentapolis, divided between the Africa province in the west, and Crete and Cyrenaica in the east. In 296 AD, the Emperor Diocletian separated the administration of Crete from Cyrenaica and in the latter formed the new provinces of "Upper Libya" and "Lower Libya", using the term Libya as a political state for the first time in history.

A centenarium is a type of Ancient Roman fortified farmhouse in the Limes Tripolitanus. It is called even in the plural centenaria, because in the Limes Tripolitanus there were more than 2000 of these "fortifications", connected to create a defensive system against desert tribe raids.

The Arch of Septimius Severus is a triumphal arch in the ruined Roman city of Leptis Magna, in present-day Libya. It was commissioned by the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus, who was born in the city. The arch was in ruins but was pieced back together by archaeologists after its discovery in 1928.

Roman colonies in North Africa are the cities—populated by Roman citizens—created in North Africa by the Roman Empire, mainly in the period between the reigns of Augustus and Trajan.

The Roman Africans or African Romans were the ancient populations of Roman North Africa that had a Romanized culture, some of whom spoke their own variety of Latin as a result. They existed from the Roman conquest until their language gradually faded out after the Arab conquest of North Africa in the Early Middle Ages.

Tripolitania was a province of the Roman Empire. Between the 2nd century BC and the 3rd century AD it had been known as Syrtica; in the 3rd century it was renamed Tripolitania meaning "region of the three cities", referring to Oea, Sabratha and Leptis Magna.