Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, commonly known as Vitruvius, was a Roman author, architect, civil and military engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work entitled De architectura. His discussion of perfect proportion in architecture and the human body led to the famous Renaissance drawing by Leonardo da Vinci of Vitruvian Man. He was also the one who, in 40 BC, invented the idea that all buildings should have three attributes: firmitas, utilitas, and venustas, meaning: strength, utility, and beauty. These principles were later adopted by the Romans.

Ancient Roman architecture adopted the external language of classical Greek architecture for the purposes of the ancient Romans, but was different from Greek buildings, becoming a new architectural style. The two styles are often considered one body of classical architecture. Roman architecture flourished in the Roman Republic and even more so under the Empire, when the great majority of surviving buildings were constructed. It used new materials, particularly Roman concrete, and newer technologies such as the arch and the dome to make buildings that were typically strong and well-engineered. Large numbers remain in some form across the empire, sometimes complete and still in use to this day.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to ancient Rome:

Sextus Julius Frontinus was a prominent Roman civil engineer, author, soldier and senator of the late 1st century AD. He was a successful general under Domitian, commanding forces in Roman Britain, and on the Rhine and Danube frontiers. A novus homo, he was consul three times. Frontinus ably discharged several important administrative duties for Nerva and Trajan. However, he is best known to the post-Classical world as an author of technical treatises, especially De aquaeductu, dealing with the aqueducts of Rome.

Hispania Tarraconensis was one of three Roman provinces in Hispania. It encompassed much of the northern, eastern and central territories of modern Spain along with the Norte Region of modern Portugal. Southern Spain, the region now called Andalusia, was the province of Hispania Baetica. On the Atlantic west laid the province of Lusitania, partially coincident with modern-day Portugal.

The Dolaucothi Gold Mines, also known as the Ogofau Gold Mine, are ancient Roman surface and underground mines located in the valley of the River Cothi, near Pumsaint, Carmarthenshire, Wales. The gold mines are located within the Dolaucothi Estate which is now owned by the National Trust.

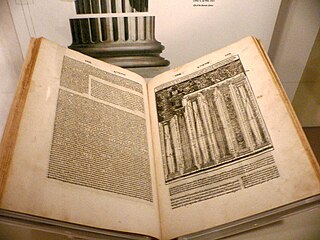

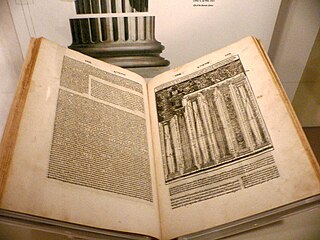

De architectura is a treatise on architecture written by the Roman architect and military engineer Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesar Augustus, as a guide for building projects. As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissance as the first book on architectural theory, as well as a major source on the canon of classical architecture. It contains a variety of information on Greek and Roman buildings, as well as prescriptions for the planning and design of military camps, cities, and structures both large and small. Since Vitruvius published before the development of cross vaulting, domes, concrete, and other innovations associated with Imperial Roman architecture, his ten books give no information on these hallmarks of Roman building design and technology.

During the growth of the ancient civilizations, ancient technology was the result from advances in engineering in ancient times. These advances in the history of technology stimulated societies to adopt new ways of living and governance.

The ancient Romans were famous for their advanced engineering accomplishments. Technology for bringing running water into cities was developed in the east, but transformed by the Romans into a technology inconceivable in Greece. The architecture used in Rome was strongly influenced by Greek and Etruscan sources.

The Aqua Appia was the first Roman aqueduct, constructed in 312 BC by the co-censors Gaius Plautius Venox and Appius Claudius Caecus, the same Roman censor who also built the important Via Appia.

The Romans constructed aqueducts throughout their Republic and later Empire, to bring water from outside sources into cities and towns. Aqueduct water supplied public baths, latrines, fountains, and private households; it also supported mining operations, milling, farms, and gardens.

Las Médulas is a historic gold-mining site near the town of Ponferrada in the comarca of El Bierzo. It was the most important gold mine, as well as the largest open-pit gold mine, in the entire Roman Empire. Las Médulas Cultural Landscape is listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. Advanced aerial surveys conducted in 2014 using LIDAR have confirmed the wide extent of the Roman-era works.

The military engineering of Ancient Rome's armed forces was of a scale and frequency far beyond that of any of its contemporaries. Indeed, military engineering was in many ways institutionally endemic in Roman military culture, as demonstrated by the fact that each Roman legionary had as part of his equipment a shovel, alongside his gladius (sword) and pila (spears).

The Barbegal aqueduct and mills is a Roman watermill complex located on the territory of the commune of Fontvieille, near the town of Arles, in southern France. The complex has been referred to as "the greatest known concentration of mechanical power in the ancient world" and the sixteen overshot wheels are considered the biggest ancient mill complex.

Mining was one of the most prosperous activities in Roman Britain. Britain was rich in resources such as copper, gold, iron, lead, salt, silver, and tin, materials in high demand in the Roman Empire. The Romans started panning and puddling for gold. The abundance of mineral resources in the British Isles was probably one of the reasons for the Roman conquest of Britain. They were able to use advanced technology to find, develop and extract valuable minerals on a scale unequaled until the Middle ages.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to classical studies:

Roman technology is the collection of techniques, skills, methods, processes, and engineering practices utilized and developed by the civilization of ancient Rome .The Roman Empire was a technologically advanced civilization of antiquity. The Romans incorporated technologies from the Greeks, Etruscans, and Celts. The technology developed by a civilization is limited by the available sources of energy, and the Romans were no different in this sense. Accessible sources of energy determine the ways in which power is generated. The main types of power accessed by the ancient Romans were human, animal, and water.

Frequently used in mines and probably elsewhere, the reverse overshot water wheel was a Roman innovation to help remove water from the lowest levels of underground workings. It is described by Vitruvius in his work De architectura published circa 25 BC. The remains of such systems found in Roman mines by later mining operations show that they were used in sequences so as to lift water a considerable height.

Hushing is an ancient and historic mining method using a flood or torrent of water to reveal mineral veins. The method was applied in several ways, both in prospecting for ores, and for their exploitation. Mineral veins are often hidden below soil and sub-soil, which must be stripped away to discover the ore veins. A flood of water is very effective in moving soil as well as working the ore deposits when combined with other methods such as fire-setting.

Metals and metal working had been known to the people of modern Italy since the Bronze Age. By 53 BC, Rome had expanded to control an immense expanse of the Mediterranean. This included Italy and its islands, Spain, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor, Syria and Greece; by the end of the Emperor Trajan's reign, the Roman Empire had grown further to encompass parts of Britain, Egypt, all of modern Germany west of the Rhine, Dacia, Noricum, Judea, Armenia, Illyria, and Thrace. As the empire grew, so did its need for metals.