Related Research Articles

Race is a categorization of humans based on shared physical or social qualities into groups generally viewed as distinct within a given society. The term came into common usage during the 16th century, when it was used to refer to groups of various kinds, including those characterized by close kinship relations. By the 17th century, the term began to refer to physical (phenotypical) traits, and then later to national affiliations. Modern science regards race as a social construct, an identity which is assigned based on rules made by society. While partly based on physical similarities within groups, race does not have an inherent physical or biological meaning. The concept of race is foundational to racism, the belief that humans can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another.

The human genome is a complete set of nucleic acid sequences for humans, encoded as the DNA within each of the 24 distinct chromosomes in the cell nucleus. A small DNA molecule is found within individual mitochondria. These are usually treated separately as the nuclear genome and the mitochondrial genome. Human genomes include both protein-coding DNA sequences and various types of DNA that does not encode proteins. The latter is a diverse category that includes DNA coding for non-translated RNA, such as that for ribosomal RNA, transfer RNA, ribozymes, small nuclear RNAs, and several types of regulatory RNAs. It also includes promoters and their associated gene-regulatory elements, DNA playing structural and replicatory roles, such as scaffolding regions, telomeres, centromeres, and origins of replication, plus large numbers of transposable elements, inserted viral DNA, non-functional pseudogenes and simple, highly repetitive sequences. Introns make up a large percentage of non-coding DNA. Some of this non-coding DNA is non-functional junk DNA, such as pseudogenes, but there is no firm consensus on the total amount of junk DNA.

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, three-dimensional structural configuration. In contrast to genetics, which refers to the study of individual genes and their roles in inheritance, genomics aims at the collective characterization and quantification of all of an organism's genes, their interrelations and influence on the organism. Genes may direct the production of proteins with the assistance of enzymes and messenger molecules. In turn, proteins make up body structures such as organs and tissues as well as control chemical reactions and carry signals between cells. Genomics also involves the sequencing and analysis of genomes through uses of high throughput DNA sequencing and bioinformatics to assemble and analyze the function and structure of entire genomes. Advances in genomics have triggered a revolution in discovery-based research and systems biology to facilitate understanding of even the most complex biological systems such as the brain.

In human genetics, the Mitochondrial Eve is the matrilineal most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of all living humans. In other words, she is defined as the most recent woman from whom all living humans descend in an unbroken line purely through their mothers and through the mothers of those mothers, back until all lines converge on one woman.

A population bottleneck or genetic bottleneck is a sharp reduction in the size of a population due to environmental events such as famines, earthquakes, floods, fires, disease, and droughts; or human activities such as genocide, speciocide, widespread violence or intentional culling. Such events can reduce the variation in the gene pool of a population; thereafter, a smaller population, with a smaller genetic diversity, remains to pass on genes to future generations of offspring. Genetic diversity remains lower, increasing only when gene flow from another population occurs or very slowly increasing with time as random mutations occur. This results in a reduction in the robustness of the population and in its ability to adapt to and survive selecting environmental changes, such as climate change or a shift in available resources. Alternatively, if survivors of the bottleneck are the individuals with the greatest genetic fitness, the frequency of the fitter genes within the gene pool is increased, while the pool itself is reduced.

The branches of science known informally as omics are various disciplines in biology whose names end in the suffix -omics, such as genomics, proteomics, metabolomics, metagenomics, phenomics and transcriptomics. Omics aims at the collective characterization and quantification of pools of biological molecules that translate into the structure, function, and dynamics of an organism or organisms.

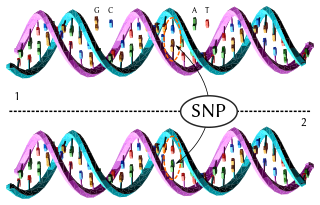

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in a sufficiently large fraction of the population, many publications do not apply such a frequency threshold.

Comparative genomics is a branch of biological research that examines genome sequences across a spectrum of species, spanning from humans and mice to a diverse array of organisms from bacteria to chimpanzees. This large-scale holistic approach compares two or more genomes to discover the similarities and differences between the genomes and to study the biology of the individual genomes. Comparison of whole genome sequences provides a highly detailed view of how organisms are related to each other at the gene level. By comparing whole genome sequences, researchers gain insights into genetic relationships between organisms and study evolutionary changes. The major principle of comparative genomics is that common features of two organisms will often be encoded within the DNA that is evolutionarily conserved between them. Therefore, Comparative genomics provides a powerful tool for studying evolutionary changes among organisms, helping to identify genes that are conserved or common among species, as well as genes that give unique characteristics of each organism. Moreover, these studies can be performed at different levels of the genomes to obtain multiple perspectives about the organisms.

Researchers have investigated the relationship between race and genetics as part of efforts to understand how biology may or may not contribute to human racial categorization. Today, the consensus among scientists is that race is a social construct, and that using it as a proxy for genetic differences among populations is misleading.

Haplogroup K or K-M9 is a genetic lineage within human Y-chromosome DNA haplogroup. A sublineage of haplogroup IJK, K-M9, and its descendant clades represent a geographically widespread and diverse haplogroup. The lineages have long been found among males on every continent except Antarctica.

Human genetic variation is the genetic differences in and among populations. There may be multiple variants of any given gene in the human population (alleles), a situation called polymorphism.

The Human Genome Project (HGP) was an international scientific research project with the goal of determining the base pairs that make up human DNA, and of identifying, mapping and sequencing all of the genes of the human genome from both a physical and a functional standpoint. It started in 1990 and was completed in 2003. It remains the world's largest collaborative biological project. Planning for the project began in 1984 by the US government, and it officially launched in 1990. It was declared complete on April 14, 2003, and included about 92% of the genome. Level "complete genome" was achieved in May 2021, with only 0.3% of the bases covered by potential issues. The final gapless assembly was finished in January 2022.

Masatoshi Nei was a Japanese-born American evolutionary biologist.

Xq28 is a chromosome band and genetic marker situated at the tip of the X chromosome which has been studied since at least 1980. The band contains three distinct regions, totaling about 8 Mbp of genetic information. The marker came to the public eye in 1993 when studies by Dean Hamer and others indicated a link between the Xq28 marker and male sexual orientation.

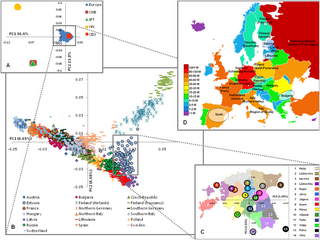

The genetic history of Europe includes information around the formation, ethnogenesis, and other DNA-specific information about populations indigenous, or living in Europe.

David Haussler is an American bioinformatician known for his work leading the team that assembled the first human genome sequence in the race to complete the Human Genome Project and subsequently for comparative genome analysis that deepens understanding the molecular function and evolution of the genome.

The multiregional hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis, is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the more widely accepted "Out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the pattern of human evolution.

A reference genome is a digital nucleic acid sequence database, assembled by scientists as a representative example of the set of genes in one idealized individual organism of a species. As they are assembled from the sequencing of DNA from a number of individual donors, reference genomes do not accurately represent the set of genes of any single individual organism. Instead, a reference provides a haploid mosaic of different DNA sequences from each donor. For example, one of the most recent human reference genomes, assembly GRCh38/hg38, is derived from >60 genomic clone libraries. There are reference genomes for multiple species of viruses, bacteria, fungus, plants, and animals. Reference genomes are typically used as a guide on which new genomes are built, enabling them to be assembled much more quickly and cheaply than the initial Human Genome Project. Reference genomes can be accessed online at several locations, using dedicated browsers such as Ensembl or UCSC Genome Browser.

The ancestry of modern Iberians is consistent with the geographical situation of the Iberian Peninsula in the South-west corner of Europe, showing characteristics that are largely typical in Southern and Western Europeans. As is the case for most of the rest of Southern Europe, the principal ancestral origin of modern Iberians are Early European Farmers who arrived during the Neolithic. The large predominance of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup R1b, common throughout Western Europe, is also testimony to a sizeable input from various waves of Western Steppe Herders that originated in the Pontic-Caspian Steppe during the Bronze Age.

The genetic history of Egypt reflects its geographical location at the crossroads of several major biocultural areas: North Africa, the Sahara, the Middle East, the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa.

References

- ↑ "Washington University in St. Louis Department of Biology Faculty".

- ↑ "Alan Templeton Curriculum Vitae". Washington University in St. Louis. Retrieved 2022-01-12.

- 1 2 Templeton, Alan R. (September 2013). "Biological races in humans". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part C: Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 44 (3): 262–271. doi:10.1016/j.shpsc.2013.04.010. PMC 3737365 . PMID 23684745.

- ↑ Templeton, A. R. (2002). "Out of Africa again and again" (PDF). Nature . 416 (6876): 45–51. Bibcode:2002Natur.416...45T. doi:10.1038/416045a. PMID 11882887. S2CID 4397398. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-12. Retrieved 2017-11-17.

- ↑ A plea to lose the race The Age, July 15, 2004

- ↑ "Big data allows computer engineers to find genetic clues in humans". March 27, 2015.

- ↑ Climer, Sharlee; Templeton, Alan R.; Zhang, Weixiong (March 27, 2015). "Human gephyrin is encompassed within giant functional noncoding yin–yang sequences". Nature Communications. 6: 6534. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.6534C. doi:10.1038/ncomms7534. PMC 4380243 . PMID 25813846.