The politics of Iran takes place in the framework of an Islamic theocracy which was formed following the overthrow of Iran's millennia-long monarchy by the 1979 Revolution. Iran's system of government (nezam) was described by Juan José Linz in 2000 as combining "the ideological bent of totalitarianism with the limited pluralism of authoritarianism". Although it "holds regular elections in which candidates who advocate different policies and incumbents are frequently defeated", Iran scored lower than Saudi Arabia in the 2021 Democracy Index, determined by the Economist Intelligence Unit.

Iran has a mixed, centrally planned economy with a large public sector. It consists of hydrocarbon, agricultural and service sectors, in addition to manufacturing and financial services, with over 40 industries traded on the Tehran Stock Exchange. With 10% of the world's proven oil reserves and 15% of its gas reserves, Iran is considered an "energy superpower". Nevertheless, since 2024 Iran is suffering from an energy crisis. Also, some allegation were made that Iran manipulates its economic data.

Education in Iran is centralized and divided into K-12 education plus higher education. Elementary and secondary education is supervised by the Ministry of Education and higher education is under the supervision of Ministry of Science, Research and Technology and Ministry of Health and Medical Education for medical sciences. As of 2016, around 94% of the Iranian adult population is literate. This rate increases to 97% among young adults ages between 15 and 24 without any gender consideration. By 2007, Iran had a student-to-workforce population ratio of 10.2%, standing among the countries with the highest ratio in the world.

The Tehran Stock Exchange (TSE) is Iran's largest stock exchange, which first opened in 1967. The TSE is based in Tehran. As of October 2024, 663 companies with a combined market capitalization of US$ 94 billion were listed on TSE. TSE, which is a founding member of the Federation of Euro-Asian Stock Exchanges, has been one of the world's best performing stock exchanges in the years 2002 through 2013. TSE is an emerging or "frontier" market.

The Central Bank of the Islamic Republic of Iran, also known as Bank Markazi, was established under the Iranian Banking and Monetary Act in 1960, it serves as the banker to the Iranian government and has the exclusive right of issuing banknote and coinage. CBI is tasked with maintaining the value of Iranian rial and supervision of banks and credit institutions. It acts as custodian of the National Jewels, as well as foreign exchange and gold reserves of Iran. It is also a founding member of the Asian Clearing Union, controls gold and capital flows overseas, represents Iran in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and internationally concludes payment agreements between Iran and other countries.

The economy of the Middle East is very diverse, with national economies ranging from hydrocarbon-exporting rentiers to centralized socialist economies and free-market economies. The region is best known for oil production and export, which significantly impacts the entire region through the wealth it generates and through labor utilization. In recent years, many of the countries in the region have undertaken efforts to diversify their economies.

The National Petrochemical Company (NPC), a subsidiary to the Iranian Petroleum Ministry, is owned by the government of the Islamic Republic of Iran. It is responsible for the development and operation of the country's petrochemical sector. Founded in 1964, NPC began its activities by operating a small fertilizer plant in Shiraz.

For health issues in Iran see Health in Iran.

The construction industry of Iran is divided into two main sections. The first is government infrastructure projects, which are central for the cement industry. The second is the housing industry. In recent years, the construction industry has been thriving due to an increase in national and international investment to the extent that it is now the largest in the Middle East region. The Central Bank of Iran indicate that 70 percent of the Iranians own homes, with huge amounts of idle money entering the housing market. Iran has three shopping malls among the largest shopping malls in the world. Iran Mall is the largest shopping mall in the world, located in Tehran. The annual turnover in the construction industry amounts to US$38.4 billion. The real estate sector contributed to 5% of GDP in 2008. Statistics from March 2004 to March 2005 put the number of total Iranian households at 15.1 million and the total number of dwelling units at 13.5 million, signifying a demand for at least 5.1 million dwelling units. Every year there is a need for 750,000 additional units as young couples embark on married life. At present, 2000 units are being built every day although this needs to increase to 2740 units. Iran's construction market will expand to $154.4 billion in 2016 from $88.7 billion in 2013.

One of the most dramatic changes in government in Iran's history was seen with the 1979 Iranian Revolution where Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi was overthrown and replaced by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. The authoritarian monarchy was replaced by a long-lasting Shiite Islamic republic based on the principle of guardianship of Islamic jurists,, where Shiite jurists serve as head of state and in many powerful governmental roles. A pro-Western, pro-American foreign policy was exchanged for one of "neither east nor west", said to rest on the three "pillars" of mandatory veil (hijab) for women, and opposition to the United States and Israel. A rapidly modernizing capitalist economy was replaced by a populist and Islamic economy and culture.

Energy in Iran is characterized by vast reserves of fossil fuels, positioning the country as a global energy powerhouse. Iran holds the world's third-largest proved oil reserves and the second-largest natural gas reserves as of 2021, accounting for 24% of the Middle East's oil reserves and 12% of the global total.

The 2007 gasoline rationing plan in Iran was launched by president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's cabinet to reduce that country's fuel consumption. Although Iran is one of the world's largest producers of petroleum, rapid increases in demand and limited refining capacity have forced the country to import about 40% of its gasoline, at an annual cost of up to USD $7 billion.

Following the Iranian Revolution, Iran's banking system was transformed to be run on an Islamic interest-free basis. As of 2010 there were seven large government-run commercial banks. As of March 2014, Iran's banking assets made up over a third of the estimated total of Islamic banking assets globally. They totaled 17,344 trillion rials, or US$523 billion at the free market exchange rate, using central bank data, according to Reuters.

Prior to 1979, Iran's economic development was rapid. Traditionally an agrarian society, by the 1970s the country had undergone significant industrialization and economic modernization. This pace of growth had slowed dramatically by 1978 as capital flight reached $30 to $40 billion 1980 US dollars just before the revolution.

The economy of Iran includes a lot of subsidies. Food items, such as flour and cooking oil, are subsidized, along with fuels such as gasoline. However cutting subsidies can cause civil unrest.

Corruption in Iran is widespread, especially in the government. According to a report in 2024, Iran ranks close to the bottom on the Corruption Perception Index of Transparency International. While Ali Khamenei claims corruption in the country is "occasional rather than systemic," corruption in Iran is an instrument of national strategy and a core feature of the political order.

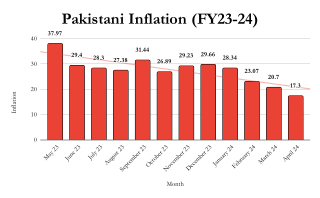

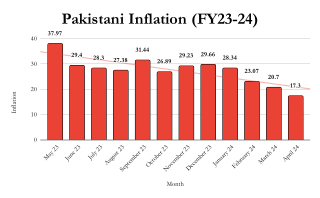

Pakistan has experienced an economic crisis as part of the 2022 political unrest. It has caused severe economic challenges for months due to which food, gas and oil prices have risen. As of 1 January 2025 Pakistan inflation rate was 4.1% lowest in 6.75 years.

As of December 2024 Iran was experiencing its deepest and longest economic crisis in its modern history. The ministry of social welfare last year announced that 57 percent of Iranians are having some level of malnourishment. Thirty percent live below the poverty line. Iranian Rial became world's least valuable currency.

The political slogans against the Islamic Republic of Iran are a series of slogans and expressions used by the Iranian public to voice opposition to the Islamic regime and its government. These slogans have developed over the years as a response to widespread discontent with the country's socio-political environment. Many Iranians say that the 1979 revolution, which overthrew the Shah's monarchy, initially promised democracy and freedom, but resulted in the establishment of a theocratic regime under the leadership of Ayatollah Khomeini. Over time, these political slogans have become a significant tool for expressing dissent, reflecting the aspirations of millions seeking freedom, justice, and systemic change in Iran.

Salaries in Iran were considerably devaluated in recent years the as Iran struggles with economic sanctions and rising inflation rates. The result is a decrease in the purchasing power of salaries. The result is that more and more citizens cannot provide themselves with the most basic needs as were defined by the government.