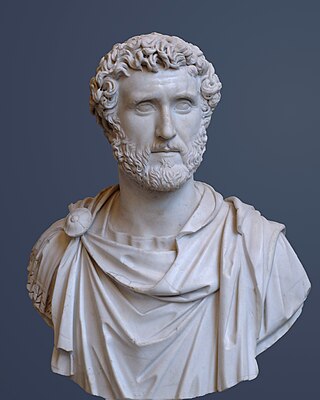

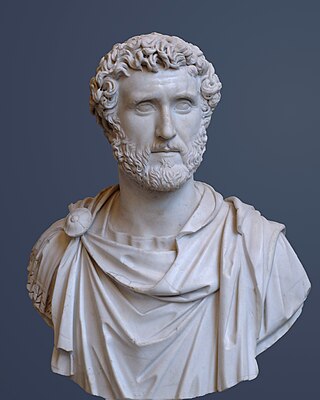

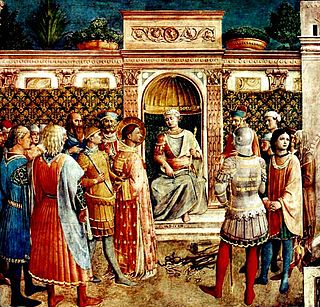

Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius was Roman emperor from AD 138 to 161. He was the fourth of the Five Good Emperors from the Nerva–Antonine dynasty.

Alcuin of York – also called Ealhwine, Alhwin, or Alchoin – was a scholar, clergyman, poet, and teacher from York, Northumbria. He was born around 735 and became the student of Archbishop Ecgbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure in the 780s and 790s. Before that, he was also a court chancellor in Aachen. "The most learned man anywhere to be found", according to Einhard's Life of Charlemagne, he is considered among the most important intellectual architects of the Carolingian Renaissance. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era.

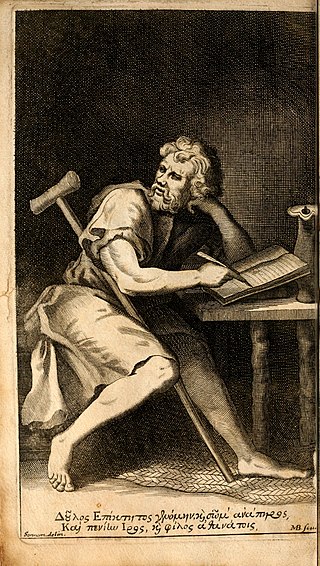

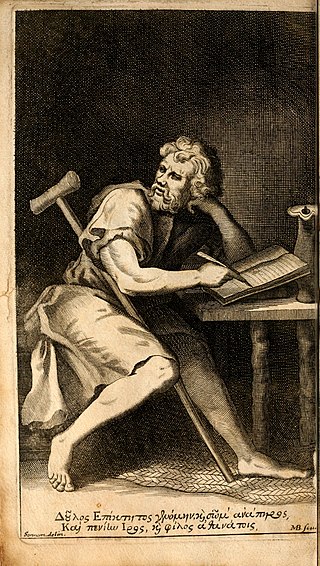

Epictetus was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia and lived in Rome until his banishment, when he went to Nicopolis in northwestern Greece, where he spent the rest of his life. His teachings were written down and published by his pupil Arrian in his Discourses and Enchiridion.

Hadrian was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, the Aeli Hadriani, came from the town of Hadria in eastern Italy. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors and the last emperor of the Pax Romana, an age of relative peace, calm, and stability for the Roman Empire lasting from 27 BC to 180 AD. He served as Roman consul in 140, 145, and 161.

The Socratic method is a form of argumentative dialogue between individuals, based on asking and answering questions.

Favorinus was a Roman sophist and skeptic philosopher who flourished during the reign of Hadrian and the Second Sophistic.

Arrian of Nicomedia was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander, and philosopher of the Roman period.

Dialogue is a written or spoken conversational exchange between two or more people, and a literary and theatrical form that depicts such an exchange. As a philosophical or didactic device, it is chiefly associated in the West with the Socratic dialogue as developed by Plato, but antecedents are also found in other traditions including Indian literature.

The Historia Augusta is a late Roman collection of biographies, written in Latin, of the Roman emperors, their junior colleagues, designated heirs and usurpers from 117 to 284. Supposedly modeled on the similar work of Suetonius, The Twelve Caesars, it presents itself as a compilation of works by six different authors, collectively known as the Scriptores Historiae Augustae, written during the reigns of Diocletian and Constantine I and addressed to those emperors or other important personages in Ancient Rome. The collection, as extant, comprises thirty biographies, most of which contain the life of a single emperor, but some include a group of two or more, grouped together merely because these emperors were either similar or contemporaneous.

Ancient Roman philosophy is philosophy as it was practiced in the Roman Republic and its successor state, the Roman Empire. Roman philosophy includes not only philosophy written in Latin, but also philosophy written in Greek in the late Republic and Roman Empire. Important early Latin-language writers include Lucretius, Cicero, and Seneca the Younger. Greek was a popular language for writing about philosophy, so much so that the Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius chose to write his Meditations in Greek.

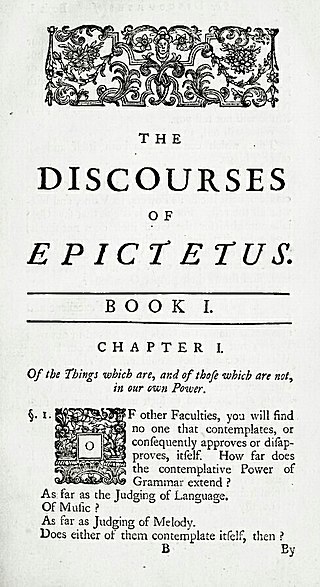

The Discourses of Epictetus are a series of informal lectures by the Stoic philosopher Epictetus written down by his pupil Arrian around 108 AD. Four books out of an original eight are still extant. The philosophy of Epictetus is intensely practical. He directs his students to focus attention on their opinions, anxieties, passions, and desires, so that "they may never fail to get what they desire, nor fall into what they avoid." True education lies in learning to distinguish what is our own from what does not belong to us, and in learning to correctly assent or dissent to external impressions. The purpose of his teaching was to make people free and happy.

Quintus Junius Rusticus, was a Roman teacher and politician. He was probably a grandson of Arulenus Rusticus, who was a prominent member of the Stoic Opposition. He was a Stoic philosopher and was one of the teachers of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, whom Aurelius treated with the utmost respect and honour.

Lucius Octavius Cornelius Publius Salvius Iulianus Aemilianus, generally referred to as Salvius Julianus, or Julian the Jurist, or simply Julianus, was a well known and respected jurist, public official, and politician who served in the Roman imperial state. Of north African origin, he was active during the long reigns of the emperors Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius, as well as the shorter reign of Marcus Aurelius' first co-Emperor, Lucius Verus.

Secundus the Silent was a philosopher who lived in Athens in the early 2nd century, who had taken a vow of silence. An anonymous text entitled Life of Secundus purports to give details of his life as well as answers to philosophical questions posed to him by the emperor Hadrian. The work enjoyed great popularity in the Middle Ages.

The early life of Marcus Aurelius spans the time from his birth on 26 April 121 until his accession as Roman emperor on 8 March 161.

The Roman–Parthian War of 161–166 was fought between the Roman and Parthian Empires over Armenia and Upper Mesopotamia. It concluded in 166 after the Romans made successful campaigns into Lower Mesopotamia and Media and sacked Ctesiphon, the Parthian capital.

The reign of Marcus Aurelius began with his accession on 7 March 161 following the death of his adoptive father, Antoninus Pius, and ended with his own death on 17 March 180. Marcus first ruled jointly with his adoptive brother, Lucius Verus. They shared the throne until Lucius' death in 169. Marcus was succeeded by his son Commodus, who had been made co-emperor in 177.

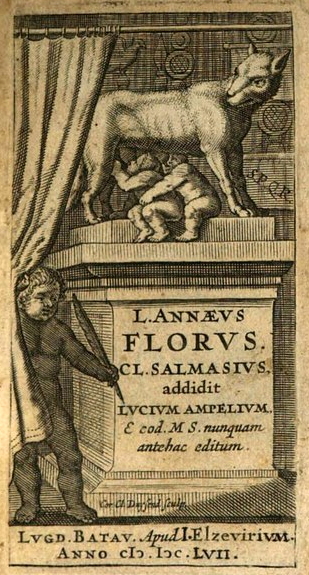

Three main sets of works are attributed to Florus : Virgilius orator an poeta, the Epitome of Roman History and a collection of 14 short poems. As to whether these were composed by the same person, or set of people, is unclear, but the works are variously attributed to:

The ioca (or joca) monachorum, meaning "monks' pastimes" or "monks' jokes", was a genre of short questions and answers for use by Christian monks. These were often on biblical subjects, but could also deal with literary, philosophical or historical matters. Although they could be straightforward, they were often riddles or jokes. They were probably used to stimulate thought and aid memory.