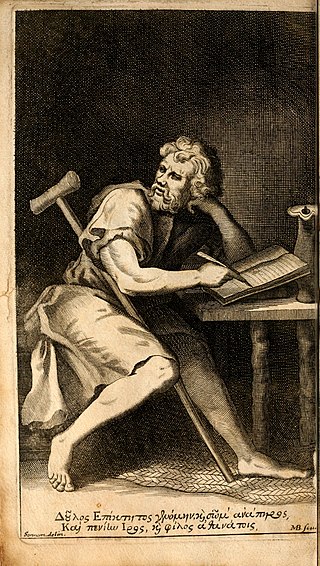

Epictetus was a Greek Stoic philosopher. He was born into slavery at Hierapolis, Phrygia and lived in Rome until his banishment, when he went to Nicopolis in northwestern Greece, where he spent the rest of his life.

The Enchiridion or Handbook of Epictetus is a short manual of Stoic ethical advice compiled by Arrian, a 2nd-century disciple of the Greek philosopher Epictetus. Although the content is mostly derived from the Discourses of Epictetus, it is not a summary of the Discourses but rather a compilation of practical precepts. Eschewing metaphysics, Arrian focuses his attention on Epictetus's work applying philosophy to daily life. Thus, the book is a manual to show the way to achieve mental freedom and happiness in all circumstances.

Zeno of Citium was a Hellenistic philosopher from Citium, Cyprus. He was the founder of the Stoic school of philosophy, which he taught in Athens from about 300 BC. Based on the moral ideas of the Cynics, Stoicism laid great emphasis on goodness and peace of mind gained from living a life of virtue in accordance with nature. It proved very popular, and flourished as one of the major schools of philosophy from the Hellenistic period through to the Roman era, and enjoyed revivals in the Renaissance as Neostoicism and in the current era as Modern Stoicism.

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy founded around 307 BCE based upon the teachings of Epicurus, an ancient Greek philosopher. Epicurus was an atomist and materialist, following in the steps of Democritus. His materialism led him to religious skepticism and a general attack on superstition and divine intervention. Epicureanism was originally a challenge to Platonism, and its main opponent later became Stoicism. It is a form of hedonism insofar as it declares pleasure to be its sole intrinsic goal. However, the concept that the absence of pain and fear constitutes the greatest pleasure, and its advocacy of a simple life, make it very different from hedonism as colloquially understood.

Diogenes Laërtius was a biographer of the Greek philosophers. Little is definitively known about his life, but his surviving Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers is a principal source for the history of ancient Greek philosophy. His reputation is controversial among scholars because he often repeats information from his sources without critically evaluating it. He also frequently focuses on trivial or insignificant details of his subjects' lives while ignoring important details of their philosophical teachings and he sometimes fails to distinguish between earlier and later teachings of specific philosophical schools. However, unlike many other ancient secondary sources, Diogenes Laërtius generally reports philosophical teachings without attempting to reinterpret or expand on them, which means his accounts are often closer to the primary sources. Due to the loss of so many of the primary sources on which Diogenes relied, his work has become the foremost surviving source on the history of Greek philosophy.

Arrian of Nicomedia was a Greek historian, public servant, military commander, and philosopher of the Roman period.

Gaius Musonius Rufus was a Roman Stoic philosopher of the 1st century AD. He taught philosophy in Rome during the reign of Nero and so was sent into exile in 65 AD, returning to Rome only under Galba. He was allowed to stay in Rome when Vespasian banished all other philosophers from the city in 71 AD although he was eventually banished anyway, returning only after Vespasian's death. A collection of extracts from his lectures still survives. He is also remembered for being the teacher of Epictetus and Dio Chrysostom.

Cleanthes, of Assos, was a Greek Stoic philosopher and boxer who was the successor to Zeno of Citium as the second head (scholarch) of the Stoic school in Athens. Originally a boxer, he came to Athens where he took up philosophy, listening to Zeno's lectures. He supported himself by working as a water-carrier at night. After the death of Zeno, c. 262 BC, he became the head of the school, a post he held for the next 32 years. Cleanthes successfully preserved and developed Zeno's doctrines. He originated new ideas in Stoic physics, and developed Stoicism in accordance with the principles of materialism and pantheism. Among the fragments of Cleanthes' writings which have come down to us, the largest is a Hymn to Zeus. His pupil was Chrysippus who became one of the most important Stoic thinkers.

Timon of Phlius was an Ancient Greek philosopher from the Hellenistic period, who was the student of Pyrrho. Unlike Pyrrho, who wrote nothing, Timon wrote satirical philosophical poetry called Silloi (Σίλλοι) as well as a number of prose writings. These have been lost, but the fragments quoted in later authors allow a rough outline of his philosophy to be reconstructed.

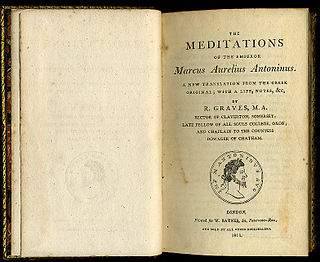

Meditations is a series of personal writings by Marcus Aurelius, Roman Emperor from 161-180 C.E., recording his private notes to himself and ideas on Stoic philosophy.

Diodorus Cronus was a Greek philosopher and dialectician connected to the Megarian school. He was most notable for logic innovations, including his master argument formulated in response to Aristotle's discussion of future contingents.

Prohairesis or proairesis is a fundamental concept in the Stoic philosophy of Epictetus. It represents the choice involved in giving or withholding assent to impressions (phantasiai). The use of this Greek word was first introduced into philosophy by Aristotle in the Nicomachean Ethics. To Epictetus, it is the faculty that distinguishes human beings from all other creatures. The concept of prohairesis plays a cardinal role in the Discourses and in the Manual: the terms "prohairesis", "prohairetic", and "aprohairetic" appear some 168 times.

Amor fati is a Latin phrase that may be translated as "love of fate" or "love of one's fate". It is used to describe an attitude in which one sees everything that happens in one's life, including suffering and loss, as good or, at the very least, necessary.

Crinis was a Stoic philosopher who lived in the 2nd and 1st centuries BC, who was contemporary with and likely a pupil of Archedemus of Tarsus. He seems to have founded an independent school within the boundaries of the Stoic system, since the authority of his followers is sometimes quoted. He is mentioned also by Arrian.

Quintus Junius Rusticus, was a Roman teacher and politician. He was probably a grandson of Arulenus Rusticus, who was a prominent member of the Stoic Opposition. He was a Stoic philosopher and was one of the teachers of the emperor Marcus Aurelius, whom Aurelius treated with the utmost respect and honour.

Panthoides was a dialectician and philosopher of the Megarian school. He concerned himself with "the logical part of philosophy", and at some point taught the Peripatetic philosopher Lyco of Troas. He wrote a book called On Ambiguities, against which the Stoic philosopher Chrysippus wrote a treatise.

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in Ancient Greece and Ancient Rome. The Stoics believed that the practice of virtue is enough to achieve eudaimonia: a well-lived life. The Stoics identified the path to achieving it with a life spent practicing the four cardinal virtues in everyday life — prudence, fortitude, temperance, and justice — as well as living in accordance with nature. It was founded in the ancient Agora of Athens by Zeno of Citium around 300 BCE.

The Boy and the Filberts is a fable related to greed and appears as Aarne-Thompson type 68A. The story is credited to Aesop but there is no evidence to support this. It is not included in either the Perry Index or in Laura Gibbs' inclusive collection (2002).

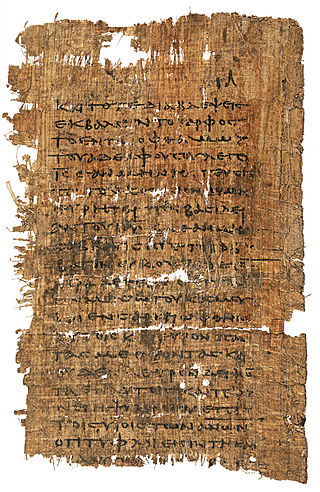

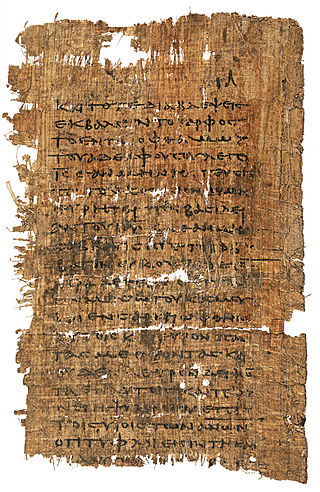

Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1 is a papyrus fragment of the logia of Jesus written in Greek. It was among the first of the Oxyrhynchus Papyri discovered by Grenfell and Hunt. It was discovered on the second day of excavation, 12 January 1897, in the garbage mounds in the Egyptian town of Oxyrhynchus. The fragment is dated to the early half of the 3rd century. Grenfell and Hunt originally dated the fragment between 150 and 300, but "probably not written much later than the year 200." It was later discovered to be the oldest manuscript of the Gospel of Thomas.

The Galilean faith is a term used by some people of the ancient world to designate Christianity. The town of Nazareth is located in Galilee. Christ's followers were thus called Galileans. Galilee was part of the province of Judea. The reason for this term was to marginalize Christianity and to indicate that it came from a small area, a religion of only local significance.