Hadrian was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, the Aeli Hadriani, came from the town of Hadria in eastern Italy. He was a member of the Nerva-Antonine dynasty.

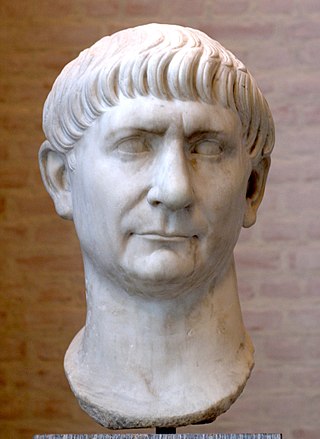

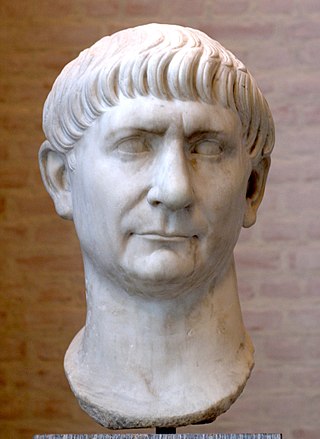

Trajan was a Roman emperor from AD 98 to 117, remembered as the second of the Five Good Emperors of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty. He was a philanthropic ruler and a successful soldier-emperor who presided over one of the greatest military expansions in Roman history, during which, by the time of his death, the Roman Empire reached its maximum territorial extent. He was given the title of Optimus by the Roman Senate.

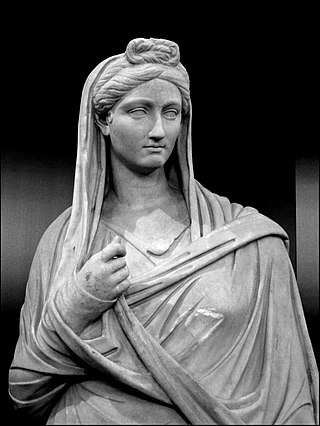

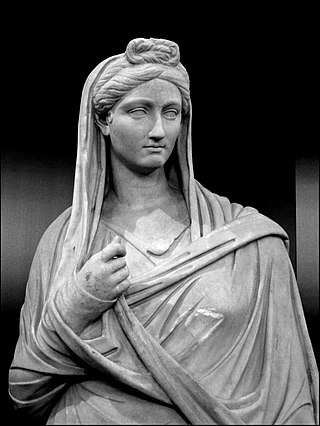

Annia Galeria Faustina the Elder, sometimes referred to as Faustina I or Faustina Major, was a Roman empress and wife of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius. The emperor Marcus Aurelius was her nephew and later became her adopted son, along with Emperor Lucius Verus. She died early in the principate of Antoninus Pius, but continued to be prominently commemorated as a diva, posthumously playing a prominent symbolic role during his reign.

Junia Calvina was a Roman noblewoman who lived in the 1st century AD.

Claudia Marcella was the name of several women of ancient Rome of the Marcelli branch of the Claudia gens. By the late Republican period girls from this branch were often called "Clodia".

Vibia Sabina (83–136/137) was a Roman Empress, wife and second cousin once removed to the Roman Emperor Hadrian. She was the daughter of Matidia and suffect consul Lucius Vibius Sabinus.

Salonia Matidia was the daughter and only child of Ulpia Marciana and wealthy praetor Gaius Salonius Matidius Patruinus. Her maternal uncle was the Roman emperor Trajan. Trajan had no children and treated her like his daughter. Her father died in 78 and Matidia went with her mother to live with Trajan and his wife, Pompeia Plotina.

Ulpia Marciana was the beloved elder sister of Roman Emperor Trajan and grandmother of empress Vibia Sabina the wife of Hadrian. Upon her death, her brother had her deified.

Livia Orestilla, alternately Cornelia Orestilla or Orestina, was the second wife of the Roman emperor Caligula in AD 37 or 38.

The gens Pompeia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome, first appearing in history during the second century BC, and frequently occupying the highest offices of the Roman state from then until imperial times. The first of the Pompeii to obtain the consulship was Quintus Pompeius in 141 BC, but by far the most illustrious of the gens was Gnaeus Pompeius, surnamed Magnus, a distinguished general under the dictator Sulla, who became a member of the First Triumvirate, together with Caesar and Crassus. After the death of Crassus, the rivalry between Caesar and Pompeius led to the Civil War, one of the defining events of the final years of the Roman Republic.

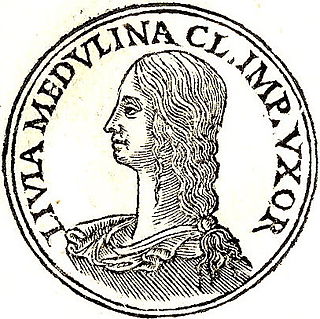

FuriaLivia Medullina Camilla was the second fiancee of the future Emperor Claudius.

Octavia the Younger was the elder sister of the first Roman emperor, Augustus, the half-sister of Octavia the Elder, and the fourth wife of Mark Antony. She was also the great-grandmother of the Emperor Caligula and Empress Agrippina the Younger, maternal grandmother of the Emperor Claudius, and paternal great-grandmother and maternal great-great-grandmother of the Emperor Nero.

Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer was a distinguished and wealthy Roman senator and soldier who lived in the Roman Empire during the 1st century. Hadrianus Afer was originally from Hispania and was of Roman descent. He was born and raised in the city of Italica in the Roman province of Hispania Baetica. He came from a well-established, wealthy and aristocratic family of Praetorian rank. He was the son of the noble Roman woman Ulpia and his father was the Roman senator, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Marullinus. Hadrianus Afer's maternal uncle was the Roman general and senator Marcus Ulpius Traianus, the father of Ulpia Marciana and her younger brother Emperor Trajan. Ulpia Marciana and Trajan were his maternal cousins.

Publius Acilius Attianus was a powerful Roman official who played a significant, though obscured, role in the transfer of power from Trajan to Hadrian.

Marcia was a Roman noblewoman and the mother of the Roman emperor Trajan.

Marcus Livius Drusus Libo was an ancient Roman consul of the early Roman Empire. He was the son of Lucius Scribonius Libo and adopted brother of the empress Livia. His natural paternal aunt was Scribonia, the second wife of Augustus, as a consequence of which he was a maternal first cousin of Julia the Elder.

Gaius Salonius Matidius Patruinus was a Roman Senator who lived in the Roman Empire during the 1st century during the reign of Vespasian.

Ulpia was a noble Roman woman from the gens Ulpia settled in Spain during the 1st century CE. She was the paternal aunt of the Roman emperor Trajan and the paternal grandmother of the emperor Hadrian.

The gens Ulpia was a Roman family that rose to prominence during the first century AD. The gens is best known from the emperor Marcus Ulpius Trajanus, who reigned from AD 98 to 117. The Thirtieth Legion took its name, Ulpia, in his honor. The city of Serdica, modern day Sofia, was renamed as Ulpia Serdica.

Decimus Terentius Scaurianus was a Roman senator and general active in the late 1st and early 2nd centuries AD. He was suffect consul in either the year 102 or 104. He worked his way up through increasingly responsible positions. He commanded a legion from 96 to 98 and again during the Second Dacian War. After the war he was military governor of the newly conquered province from 106 to 111. He is known to have been decorated for his military service.