Related Research Articles

In Norse mythology, Ullr is a god associated with skiing. Although literary attestations of Ullr are sparse, evidence including relatively ancient place-name evidence from Scandinavia suggests that he was a major god in earlier Germanic paganism. Proto-Germanic *wulþuz ('glory') appears to have been an important concept of which his name is a reflex. The word appears as owlþu- on the 3rd-century Thorsberg chape.

Gamla Uppsala is a parish and a village outside Uppsala in Sweden. It had 17,973 inhabitants in 2016.

Józef Ignacy Kraszewski was a Polish novelist, journalist, historian, publisher, painter, and musician.

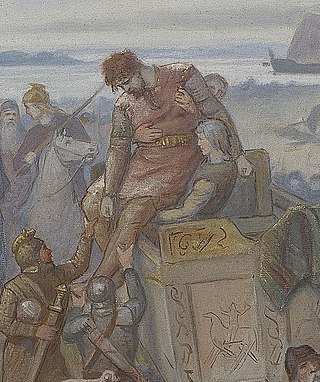

The Battle of Svolder was a large naval battle during the Viking age, fought in September 1000 in the western Baltic Sea between King Olaf of Norway and an alliance of the Kings of Denmark and Sweden and Olaf's enemies in Norway. The backdrop of the battle was the unification of Norway into a single independent state after longstanding Danish efforts to control the country, combined with the spread of Christianity in Scandinavia.

John I Albert was King of Poland from 1492 to his death and Duke of Głogów from 1491 to 1498. He was the fourth Polish sovereign from the Jagiellonian dynasty and the son of Casimir IV and Elizabeth of Austria.

The Livonian Chronicle of Henry is a Latin narrative of events in Livonia and surrounding areas from 1180 to 1227. It was written c. 1229 by a priest named Henry. Apart from some references in Gesta Danorum – a patriotic work by the 12th-century Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus – and few mentions in the Primary Chronicle compiled in Kievan Rus', the Chronicle of Henry is the oldest known written document about the history of Estonia and Latvia.

Vytautas, also known as Vytautas the Great, was a ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He was also the prince of Grodno (1370–1382), prince of Lutsk (1387–1389), and the postulated king of the Hussites.

Various gods and men appear as sons of Odin in Old Norse and Old English texts.

Harald Wartooth or Harold Hiltertooth was a semi-legendary king of Denmark who is mentioned in several traditional sources. He is held to have (indirectly) succeeded his father as king of Zealand and to have expanded his realm. According to different sources, he may have ruled over Jutland, part of Sweden and the historical northern German province of Wendland. He is said to have been finally defeated and killed at the legendary Battle of Bråvalla.

Styrbjörn the Strong according to late Norse sagas was a son of the Swedish king Olof, and a nephew of Olof's co-ruler and successor Eric the Victorious, who defeated and killed Styrbjörn at the Battle of Fyrisvellir. As with many figures in the sagas, doubts have been cast on his existence, but he is mentioned in a roughly contemporaneous skaldic poem about the battle. According to legend, his original name was Björn, and Styr-, which was added when he had grown up, was an epithet meaning that he was restless, controversially forceful and violent.

Starkad was either an eight-armed giant or the human grandson of the aforementioned giant in Norse mythology.

The blood eagle was a method of ritual execution as detailed in late skaldic poetry. According to the two instances mentioned in the Christian sagas, the victims were placed in a prone position, their ribs severed from the spine with a sharp tool, and their lungs pulled through the opening to create a pair of "wings". There has been continuing debate about whether the rite was a literary invention of the original texts, a mistranslation of the texts themselves, or an authentic historical practice.

Pilėnai was a hill fort in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Its location is unknown and is subject to academic debates, but it is well known in the history of Lithuania due to its heroic defense against the Teutonic Order in 1336. Attacked by a large Teutonic force, the fortress, commanded by Duke Margiris, tried in vain to organize a defense against the larger and stronger invader. Losing hope, the defenders decided to burn their property and commit mass suicide to deprive the Order of prisoners and loot. This dramatic episode from the Lithuanian Crusade has caught the public imagination, inspired many works of fiction, and became a symbol of Lithuanian struggles and resistance.

Teodor Narbutt was a Polish–Lithuanian romantic historian and military engineer in service of the Russian Empire. He is best remembered as the author of a nine-volume Polish-language history of Lithuania from the early Middle Ages to the Union of Lublin.

Oeselians or Osilians is a historical name for the people who prior to the Northern Crusades in the 13th century lived in the Estonian island of Saaremaa (Ösel) – the Baltic Sea island was also referred as Oeselia or Osilia in written records dating from around that time. In Viking Age literature, the inhabitants were often included under the name "Vikings from Estonia", as written by Saxo Grammaticus in the late 12th century. The earliest known use of the word in the (Latinised) form of "Oeselians" in writing was by Henry of Livonia in the 13th century. The inhabitants of Saaremaa (Ösel) are also mentioned in a number of historic written sources dating from the Estonian Viking Age.

Milda, in the Lithuanian mythology, is the goddess of love. However, her authenticity is debated by scholars. Despite the uncertainty, Milda became a popular female given name in Lithuania. Neo-pagan societies and communities, including Romuva, organize various events in honor of goddess Milda in May. The Milda Mons, a mountain on Venus, is named after her.

Nijolė is a Lithuanian feminine given name. It is one of the numerous pseudomythological names invented in the 19th century by Lithuanian writer Teodor Narbutt for Lithuanian pagan mythology. See List of Lithuanian gods and mythological figures for more.

Šventaragis' Valley is a valley at the confluence of Neris and Vilnia Rivers in Vilnius, Lithuania. According to a legend recorded in the Lithuanian Chronicles, it was where Lithuanian rulers were cremated before the Christianization of Lithuania in 1387. Maciej Stryjkowski further recorded that it was the location of a pagan temple dedicated to Perkūnas, the god of thunder. While the legends are generally dismissed as fiction by historians, they have been studied and analysed from the perspective of pre-Christian Lithuanian mythology by Vladimir Toporov, Gintaras Beresnevičius, Norbertas Vėlius, Vykintas Vaitkevičius, and others.

A zhrets is a priest in the Slavic religion whose name is reconstructed to mean "one who makes sacrifices". The name appears mainly in the East and South Slavic vocabulary, while in the West Slavs it is attested only in Polish. Most information about the Slavic priesthood comes from Latin texts about the paganism of the Polabian Slavs. The descriptions show that they were engaged in offering sacrifices to the gods, divination and determining the dates of festivals. They possessed cosmological knowledge and were a major source of resistance against Christianity.

References

- 1 2 "Anapilis", Universal Lithuanian Encyclopedia

- 1 2 3 4 Justyna Prusinowska, "Anafielas i Walhalla przeglądają się w Niemnie. Wędrówka w zaświaty litewskie i skandynawskie", Science Journals . Folk Architecture Museum and Ethnographic Park in Olwsztynek, vol. 1, no. 1, 2010, pp. 47-63

- ↑ "Ar vartotinas pasakymas „išėjo anapilin (Anapilin)“, didžiąja ar mažąja raide reikėtų rašyti žodį „anapilis“?", State commission of the Lithuanian language. Consultation Bank

- ↑ Bronys Savukynas, "Mitologizuota pseudomitinių vardų vartosena: Anapilis", Gimtoji kalba, 2000, no. 7–9, pp. 17–19)

- ↑ Bronys Savukynas, Mažųjų "Kasdienybės mitų" atšvaitai Lietuvių vardyne, Naujasis Židinys - Aidai, 2000, No. 7-8, pp. 369-372

- ↑ Theodor Narbutt, Dzieje starożytne narodu litewskiego, vol. 1, 1835, pp.384-385

- ↑ Saxo Grammaticus: Gesta Danorum: 6.5

- ↑ Museum-archives