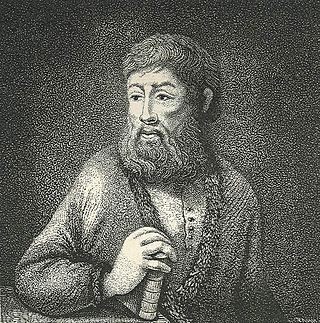

Count Andrey Artamonovich Matveev ( ‹See Tfd› Russian : Андрей Артамонович Матвеев) (1666–1728) was a Russian statesman of the Petrine epoch best remembered as one of the first Russian ambassadors and Peter the Great's agent in London and The Hague.

Andrey Matveyev was the son of the more famous Artamon Matveyev by a Scottish woman, Eudoxia Hamilton. At the age of eight he was granted a rank of chamber stolnik (комнатный стольник) but was exiled together with his father during Feodor III's early reign. The Matveyevs returned to Moscow on 11 May 1682, and four days later Artamon Matveyev was killed by the rebellious Streltsy during the Moscow Uprising of 1682, while Andrey fled the capital again. In 1691–1693 he served as voyevoda in the Dvina Region.

Peter the Great, who had deeply respected Matveyev the elder and whose own mother had been brought up in the Matveyev family, sent him in 1700 as ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary, firstly in the Dutch Republic (1699–1712), afterwards in Austria (1712–1715), where he was granted in 1715 a comital title of the Holy Roman Empire. In 1705, Matveev did not succeed in his Paris mission to treat with France on trade issues. He then settled in London with the purpose of persuading Queen Anne to mediate between Sweden and Russia and not to acknowledge Stanisław Leszczyński as King of Poland.

Just before leaving England, Matveyev was accosted and apprehended by some bailiffs, "a Brutal sort of People", who made his release from the Sponging-house contingent on payment of £50. Having suffered verbal and physical abuse, Matveyev reported to the Russian Foreign Office that the English "have no respect for common law whatsoever". Despite subsequent apologies from the Parliament and the Queen, the diplomatic corps in London raised such an outcry over the incident that it led the Parliament to adopt the Diplomatic Privileges Act 1708 (7 Ann. c. 12), the first-ever act to guarantee diplomatic immunity. [1]

In 1716, Matveyev was recalled to St Petersburg, where he received the rank of Privy Counsellor and was appointed to run a naval academy. Three years later, he became Senator and President of Justice Collegium. For three years before his retirement in 1727 he presided over the senate office in Moscow. His daughter Maria — rumoured to have been the tsar's mistress — was the mother of Field-Marshal Peter Rumyantsev.

In his declining years, presumably influenced by Pyotr Shafirov's research on Russian history, Matveyev described the Moscow Uprising of 1682, appending a summary account of the subsequent events up to 1698. The book is written in florid, antiquated language replete with outlandish spellings. It has a tangible bias: the actions of tsarevna Sofia and her party are painted as evil, while those of the Naryshkins and the author's father are immoderately glorified.