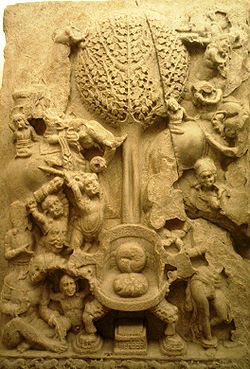

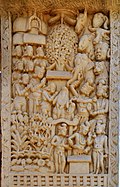

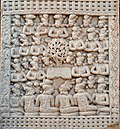

Since the beginning of the serious study of the history of Buddhist art in the 1890s, the earliest phase, lasting until the 1st century CE, has been described as aniconic; the Buddha was only represented through symbols such as an empty throne, Bodhi tree, a riderless horse with a parasol floating above an empty space (at Sanchi), Buddha's footprints, and the dharma wheel. [2]

Contents

This aniconism in relation to the image of the Buddha could be in conformity with an ancient Buddhist prohibition against showing the Buddha himself in human form, known from the Sarvastivada vinaya (rules of the early Buddhist school of the Sarvastivada):

"Since it is not permitted to make an image of the Buddha's body, I pray that the Buddha will grant that I can make an image of the attendant Bodhisattva. Is that acceptable?" The Buddha answered: "You may make an image of the Bodhisattava". [3]

Although there is still some debate, the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha himself are often considered a result of the Greco-Buddhist interaction, in particular in Gandhara, a theory first fully expounded by Alfred A. Foucher, but criticised from the start by Ananda Coomaraswamy. Foucher also accounted for the origins of the aniconic symbols themselves in small souvenirs carried away from the main pilgrimage sites and so becoming recognised and popularized as symbolic of the events associated with the site. Other explanations were that it was inappropriate to represent one who had attained nirvana. [4]

However, in 1990, the notion of aniconism in Buddhism was challenged by Susan Huntington, initiating a vigorous debate among specialists that still continues. [5] She sees many early scenes claimed to be aniconic as in fact not depicting scenes from the life of the Buddha, but worship of cetiya (relics) or re-enactments by devotees at the places where these scenes occurred. Thus the image of the empty throne shows an actual relic-throne at Bodh Gaya or elsewhere. She points out that there is only one indirect reference for a specific aniconic doctrine in Buddhism to be found, and that pertaining to only one sect. [6]

As for the archeological evidence, it shows some anthropomorphic sculptures of the Buddha actually existing during the supposedly aniconic period, which ended during the 1st century CE.[ citation needed ] Huntington also rejects the association of "aniconic" and "iconic" art with an emerging division between Theravada and Mahayana Buddhism. Huntington's views have been challenged by Vidya Dehejia and others. [7] Although some earlier examples have been found in recent years, it is common ground that the large free-standing iconic images of the Buddha so prominent in later Buddhist art are not found in the earliest period; discussion is focused on smaller figures in relief panels, conventionally considered to represent scenes from the life of the Buddha, and now re-interpreted by Huntington and her supporters.

- Pillar with Naga Mucalinda protecting the throne of the Buddha. Railing pillar from Jagannath Tekri, Pauni (Bhandara District). 2nd–1st century BCE. National Museum of India. [8]

- Devotions to the empty throne of the Buddha, Kanaganahalli, 1st–3rd century CE