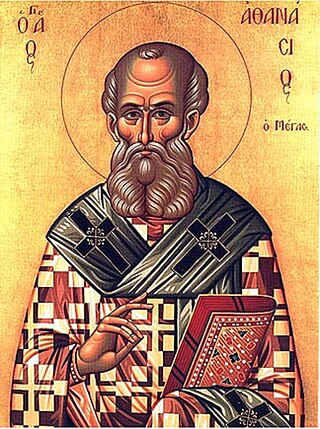

Athanasius I of Alexandria, also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Coptic church father and the 20th pope of Alexandria. His intermittent episcopacy spanned 45 years, of which over 17 encompassed five exiles, when he was replaced on the order of four different Roman emperors. Athanasius was a Christian theologian, a Church Father, the chief defender of Trinitarianism against Arianism, and a noted Egyptian Christian leader of the fourth century.

The Coptic Orthodox Church, also known as the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria, is an Oriental Orthodox Christian church based in Egypt, servicing Africa and the Middle East. The head of the church and the See of Alexandria is the Pope of Alexandria on the Holy Apostolic See of Saint Mark, who also carries the title of Father of fathers, Shepherd of Shepherds, Ecumenical Judge and the thirteenth among the Apostles. The See of Alexandria is titular, and today, the Coptic Pope presides from Saint Mark's Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in the Abbassia District in Cairo. The church follows the Coptic Rite for its liturgy, prayer and devotional patrimony. The church has approximately 25 million members worldwide and is Egypt's largest Christian denomination.

Copts are a Christian ethnoreligious group indigenous to North Africa who have primarily inhabited the area of modern Egypt and Sudan since antiquity. Most ethnic Copts are Coptic Oriental Orthodox Christians. They are the largest Christian denomination in Egypt and the Middle East, as well as in Sudan and Libya. Copts have historically spoken the Coptic language, a direct descendant of the Demotic Egyptian that was spoken in late antiquity.

The Muslim conquest of Egypt, led by the army of 'Amr ibn al-'As, took place between 639 and 646 AD and was overseen by the Rashidun Caliphate. It ended the seven-century-long period of Roman reign over Egypt that began in 30 BC. Byzantine rule in the country had been shaken, as Egypt had been conquered and occupied for a decade by the Sasanian Empire in 618–629, before being recovered by the Byzantine emperor Heraclius. The caliphate took advantage of Byzantines' exhaustion and captured Egypt ten years after its reconquest by Heraclius.

Pope Benjamin I of Alexandria, 38th Pope of Alexandria & Patriarch of the See of St. Mark. He is regarded as one of the greatest patriarchs of the Coptic Church. Benjamin guided the Coptic church through a period of turmoil in Egyptian history that included the fall of Egypt to the Sassanid Empire, followed by Egypt's reconquest under the Byzantines, and finally the Arab Islamic Conquest in 642. After the Arab conquest Pope Benjamin, who was in exile, was allowed to return to Alexandria and resume the patriarchate.

Religion in Egypt controls many aspects of social life and is endorsed by law. The state religion of Egypt is Islam. Although estimates vary greatly in the absence of official statistics. Since the 2006 census religion has been excluded, and thus available statistics are estimates made by religious and non-governmental agencies. The country is majority Sunni Muslim, with the next largest religious group being Coptic Orthodox Christians. The exact numbers are subject to controversy, with Christians alleging that they have been systemically under-counted in existing censuses.

Seeing Islam As Others Saw It: A Survey and Evaluation of Christian, Jewish and Zoroastrian Writings on Early Islam from the Studies in Late Antiquity and Early Islam series is a book by scholar of the Middle East Robert G. Hoyland.

Christianity is the second largest religion in Egypt. The history of Egyptian Christianity dates to the Roman era as Alexandria was an early center of Christianity.

Coptic history is the part of the history of Egypt that begins with the introduction of Christianity in Egypt in the 1st century AD during the Roman period, and covers the history of the Copts to the present day. Many of the historic items related to Coptic Christianity are on display in many museums around the world and a large number is in the Coptic Museum in Coptic Cairo.

Forces of the Rashidun Caliphate seized the major Mediterranean port of Alexandria away from the Eastern Roman Empire in the middle of the 7th century AD. Alexandria had been the capital of the Byzantine province of Egypt. This ended Eastern Roman maritime control and economic dominance of the Eastern Mediterranean and thus continued to shift geopolitical power further in favor of the Rashidun Caliphate.

Oriental Orthodoxy is the communion of Eastern Christian Churches that recognize only three ecumenical councils—the First Council of Nicaea, the First Council of Constantinople and the Council of Ephesus. They reject the dogmatic definitions of the Council of Chalcedon. Hence, these Churches are also called Old Oriental Churches or Non-Chalcedonian Churches.

The Oriental Orthodox Churches are Eastern Christian churches adhering to Miaphysite Christology, with approximately 60 million members worldwide. The Oriental Orthodox Churches are part of the Nicene Christian tradition, and represent one of its oldest branches.

The Islamization of Egypt occurred as a result of the Muslim conquest of Egypt by the Arabs led by the prominent Muslim general Amr ibn al-As, the military governor of the Holy Land. The masses of locals in Egypt and the rest of the Middle East underwent a large scale gradual conversion from Christianity to Islam, accompanied by jizya for those who refused to convert. This is attested to by John of Nikiû, a coptic bishop who wrote about the conquest, and who was a near contemporary of the events he described. The process of Islamization was accompanied by a simultaneous wave of Arabization. These factors resulted in Islam becoming the dominant faith in Egypt between 10th and 12th century, Egyptians acculturating into an Islamic identity and then replacing Coptic and Greek languages, which were spoken as a result of the Greek and Roman occupation of Egypt, with Arabic as their sole vernacular which became the language of the nation by law.

Athanasius I Gammolo was the Patriarch of Antioch and head of the Syriac Orthodox Church from 594/595 or 603 until his death in 631. He is commemorated as a saint by the Syriac Orthodox Church in the Martyrology of Rabban Sliba, and his feast day is 3 January.

The Apocalypse of Pseudo-Athanasius is an apocalyptic sermon authored between 715 and 744 during the Umayyad Caliphate. Very popular, the work was found in multiple Coptic manuscripts and in Arabic translations. The text most likely served as an influence for both Coptic and Copto-Arabic writings and is also a rare witness to the reaction of Copts towards the Muslim conquest of Egypt. Though Islamic practices of faith are absent from the text, it still provides the author's Coptic perspective to the fundamental historic changes in their country and the everyday-lives of the inhabitants.

The Apocalypse of Shenute is a short Coptic apocalyptic text which purports to be a prophecy of Shenute from Christ about the eschaton. The Coptic Apocalypse of Elijah greatly influenced the text. It is the oldest miaphysite Coptic apocalypse to survive from the Islamic period, a rare contemporary witness to Coptic–Muslim relations in the earliest period, one of the earliest miaphysite Coptic sources to mention the Islamic rejection of the crucifixion of Christ, and a response to the Islamic conversion of Copts.

The Passion of the Sixty Martyrs of Gaza is a hagiography text pertaining to the martyrdom of sixty Byzantine soldiers at Gaza. Contrary to many hagiographies which martyrs were killed for religious reasons, martyrs had also died for either military, political, or non-religious reasons such as in the Passion of the Sixty Martyrs of Gaza. Palestine 's history during Muslim conquest in the Greek original Passion of the Sixty Martyrs of Gaza contains unique details of significant events along with Jerusalem's early occupation by the Muslims. The text is also an early witness to many of these events predating Theophilus of Edessa, even contradicting him such as Gaza's surrender on a different date and Sophronius's circumstances leading to his death.

The Apocalypse of Peter or Vision of Peter, also known as the Book of the Rolls and other titles, is a Miaphysite Christian work probably written in the 10th century; the late 9th century and 11th century are also considered plausible. Around 40 manuscripts of it have been preserved and found. It is pseudepigraphically attributed to Clement of Rome, relating a vision experienced by the Apostle Peter of the resurrected Jesus; the actual author is unknown. The work was originally written in Arabic; many Ethiopic manuscripts exist as well, with the reworked Ethiopic version in the work Clement along with other stories of Clementine literature.

Copto-Arabic literature is the literature of the Copts written in Arabic. It is distinct from Coptic literature, which is literature written in the Coptic language.