Arno Ros (born 18 December 1942 in Hamburg) is a German philosopher and Professor of Theoretical Philosophy at the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg in Magdeburg, Germany.

Arno Ros (born 18 December 1942 in Hamburg) is a German philosopher and Professor of Theoretical Philosophy at the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg in Magdeburg, Germany.

Ros studied Ibero-Romance languages, sociology, literature and philosophy in Hamburg, Madrid (Spain) and Coimbra (Portugal). He received his doctorate in 1971 for the dissertation On the theory of literary narrative. He earned his habilitation in Saarbrücken as an assistant of Kuno Lorenz. The title of his habilitation thesis was Philosophy as a methodological critique of meaning. In subsequent years, Ros was a visiting professor in Hamburg, Saarbrücken and Campinas (Brazil).

Since 1994 he is professor for Theoretical Philosophy at the Otto-von-Guericke University Magdeburg. His main focus is concentrated on systematic and historical problems of argumentation theory with special attention to the theory of concepts (the concept of concept) as well as systematic and historical questions of philosophy of biology and psychology, with particular reference to the philosophical aspects of the mind-matter problem.

Among his students, he is best known and appreciated for his conceptually accurate argumentation and teaching. In his lectures he takes particular care to examine complicated problems by clearly distinguishing between their logical-methodological and historical components.

Ros is known (also because of his activities as a former assistant of Kuno Lorenz) as an expert in argumentation theory and in this field he has researched the concepts of concept, of foundation, of explanation as well as of a typology of explanations (which are distinguished by the different types of causes that they provide). From 1989 to 1990, Ros published Foundation and Concept, a three volume monograph on the concept of concept that spans the history of philosophy from its beginnings in ancient Greece to contemporary Analytical Philosophy.

The term 'concept' is understood by Ros along lines suggested by Ludwig Wittgenstein's later work, that is, as a linguistic classificatory ability or habit. The epistemological starting point is that we as subjects can only acquire knowledge about parts of the world by classifying objects (entities), that is, by making use of our classificatory abilities. The problem lies in the fact that our classificatory abilities may be learned, dependent on culture, or biologically conditioned, whereby the possibility of objective justification can be called into question. From this arises the task of philosophy, which, unlike the sciences, does not use or apply our classificatory abilities to interpret reality, but rather reflects upon these very conceptual abilities, that is, investigates whether they are meaningful or reasonable.

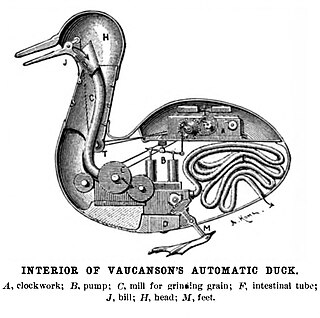

As an argumentation theorist, Ros especially emphasizes that within the philosophy of mind it is critical to first of all specify the problem as exactly as possible. Physical processes have to be distinguished from biological processes because the latter, in contrast to the former, when related to the activities of an organism, are purposeful and are meant as a response to a stimulus. From the concept of organism Ros progresses to the concept of the agent or acting subject, and from this to the concept of person, which is characterized by the criterion of possessing psychological phenomena. In the case of humans, an additional stage is reached, because they are also able to guide themselves by rules.

In Matter and Spirit (2005), Ros presented a thorough analysis of the mind-matter problem. In 2008, he published the essay "Mental Causation and Mereological Explanations", in which he tries to solve the problem of mental causation by means of mereological explanations.

In addition, he has recently published the following papers on the philosophy of mind:

Ros speaks in the philosophy of mind expressly of psychological (German, psychische) phenomena instead of mental (German, mentale) or spiritual (German, geistige) states (as is common in the current debate). For him, only higher cognitive functions (such as problem solving, use of abstract concepts, etc.) qualify as mental or spiritual, while psychological phenomena must include states such as temper tantrums. Ros therefore avoids using the terms mental and spiritual. After all, the German word Geist is merely a corresponding term for the Greek concept of psyche.

This is a selection of the works of Arno Ros. The full list of publications can be found in the external links below.

Concepts are defined as abstract ideas or general notions that occur in the mind, in speech, or in thought. They are understood to be the fundamental building blocks of thoughts and beliefs. They play an important role in all aspects of cognition. As such, concepts are studied by several disciplines, such as linguistics, psychology, and philosophy, and these disciplines are interested in the logical and psychological structure of concepts, and how they are put together to form thoughts and sentences. The study of concepts has served as an important flagship of an emerging interdisciplinary approach called cognitive science.

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substance" view of the nature of reality as opposed to a "two-substance" (dualism) or "many-substance" (pluralism) view. Both the definition of "physical" and the meaning of physicalism have been debated.

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas regarding the associations between phenomena, which can be described in terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena. It is also described as an intellectual and philosophical position that interprets a complex system as the sum of its parts.

Solipsism is the philosophical idea that only one's mind is sure to exist. As an epistemological position, solipsism holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure; the external world and other minds cannot be known and might not exist outside the mind.

In the philosophy of mind, mind–body dualism denotes either the view that mental phenomena are non-physical, or that the mind and body are distinct and separable. Thus, it encompasses a set of views about the relationship between mind and matter, as well as between subject and object, and is contrasted with other positions, such as physicalism and enactivism, in the mind–body problem.

In philosophy of mind, functionalism is the thesis that mental states are constituted solely by their functional role, which means, their causal relations with other mental states, sensory inputs and behavioral outputs. Functionalism developed largely as an alternative to the identity theory of mind and behaviorism.

Eliminative materialism is the claim that certain types of mental states that most people believe in do not exist. It is a materialist position in the philosophy of mind. Some supporters of eliminativism argue that no coherent neural basis will be found for many everyday psychological concepts such as belief or desire, since they are poorly defined. Rather, they argue that psychological concepts of behaviour and experience should be judged by how well they reduce to the biological level. Other versions entail the non-existence of conscious mental states such as pain and visual perceptions.

In the philosophy of mind, emergentmaterialism is a theory which asserts that the mind is irreducibly existent in some sense. However, the mind does not exist in the sense of being an ontological simple. Further, the study of mental phenomena is independent of other sciences. The theory primarily maintains that the human mind's evolution is a product of material nature and that it cannot exist without material basis.

The hard problem of consciousness is the problem of explaining why and how we have qualia or phenomenal experiences. That is to say, it is the problem of why we have personal, first-person experiences, often described as experiences that feel "like something." In comparison, we assume there are no such experiences for inanimate things like, for instance, a thermostat, toaster, computer, or a sophisticated form of artificial intelligence. The philosopher David Chalmers, who introduced the term "hard problem of consciousness," contrasts this with the "easy problems" of explaining the physical systems that give us and other animals the ability to discriminate, integrate information, report mental states, focus attention, and so forth. Easy problems are (relatively) easy because all that is required for their solution is to specify a mechanism that can perform the function. That is, even though we have yet to solve most of the easy problems, these questions can probably eventually be understood by relying entirely on standard scientific methods. Chalmers claims that even once we have solved such problems about the brain and experience, the hard problem will "persist even when the performance of all the relevant functions is explained".

A philosophical zombie or p-zombie argument is a thought experiment in philosophy of mind that imagines a hypothetical being that is physically identical to and indistinguishable from a normal person but does not have conscious experience, qualia, or sentience. For example, if a philosophical zombie were poked with a sharp object it would not inwardly feel any pain, yet it would outwardly behave exactly as if it did feel pain, including verbally expressing pain. Relatedly, a zombie world is a hypothetical world indistinguishable from our world but in which all beings lack conscious experience.

In philosophy, emergentism is the belief in emergence, particularly as it involves consciousness and the philosophy of mind, and as it contrasts with and also does not contrast with reductionism. A property of a system is said to be emergent if it is a new outcome of some other properties of the system and their interaction, while it is itself different from them.

Frank Cameron JacksonFBA is an Australian analytic philosopher and Emeritus Professor in the School of Philosophy at Australian National University (ANU). Jackson spent much of his career at ANU (1986–2014) and he was a regular visiting professor of philosophy at Princeton University (2007–14). His research focuses primarily on the philosophy of mind, epistemology, metaphysics, and meta-ethics.

Jaegwon Kim was a Korean-American philosopher. At the time of his death, Kim was an emeritus professor of philosophy at Brown University. He also taught at several other leading American universities during his lifetime, including the University of Michigan, Cornell University, the University of Notre Dame, Johns Hopkins University, and Swarthmore College. He is best known for his work on mental causation, the mind-body problem and the metaphysics of supervenience and events. Key themes in his work include: a rejection of Cartesian metaphysics, the limitations of strict psychophysical identity, supervenience, and the individuation of events. Kim's work on these and other contemporary metaphysical and epistemological issues is well represented by the papers collected in Supervenience and Mind: Selected Philosophical Essays (1993).

Type physicalism is a physicalist theory in the philosophy of mind. It asserts that mental events can be grouped into types, and can then be correlated with types of physical events in the brain. For example, one type of mental event, such as "mental pains" will, presumably, turn out to be describing one type of physical event.

Physical causal closure is a metaphysical theory about the nature of causation in the physical realm with significant ramifications in the study of metaphysics and the mind. In a strongly stated version, physical causal closure says that "all physical states have pure physical causes" — Jaegwon Kim, or that "physical effects have only physical causes" — Agustin Vincente, p. 150.

The problem of mental causation is a conceptual issue in the philosophy of mind. That problem, in short, is how to account for the common-sense idea that intentional thoughts or intentional mental states are causes of intentional actions. The problem divides into several distinct sub-problems, including the problem of causal exclusion, the problem of anomalism, and the problem of externalism. However, the sub-problem which has attracted most attention in the philosophical literature is arguably the exclusion problem.

Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that studies the ontology and nature of the mind and its relationship with the body. The mind–body problem is a paradigmatic issue in philosophy of mind, although a number of other issues are addressed, such as the hard problem of consciousness and the nature of particular mental states. Aspects of the mind that are studied include mental events, mental functions, mental properties, consciousness, the ontology of the mind, the nature of thought, and the relationship of the mind to the body.

The mind–body problem is a debate concerning the relationship between thought and consciousness in the human mind, and the brain as part of the physical body. It is distinct from the question of how mind and body function chemically and physiologically, as that question presupposes an interactionist account of mind–body relations. This question arises when mind and body are considered as distinct, based on the premise that the mind and the body are fundamentally different in nature.

Interactionism or interactionist dualism is the theory in the philosophy of mind which holds that matter and mind are two distinct and independent substances that exert causal effects on one another. It is one type of dualism, traditionally a type of substance dualism though more recently also sometimes a form of property dualism.

The study of the mind in Eastern philosophy has parallels to the Western study of the Philosophy of mind as a branch of philosophy that studies the nature of the mind. Dualism and monism are the two central schools of thought on the mind–body problem in the Western tradition, although nuanced views have arisen that do not fit one or the other category neatly. Dualism is found in both Eastern and Western traditions but its entry into Western philosophy was thanks to René Descartes in the 17th century. This article on mind in eastern philosophy deals with this subject from the standpoint of eastern philosophy which is historically strongly separated from the Western tradition and its approach to the Western philosophy of mind.