Related Research Articles

The 1967 Detroit Riot, also known as the 12th Street Riot or Detroit Rebellion, was the bloodiest of the urban riots in the United States during the "Long, hot summer of 1967". Composed mainly of confrontations between black residents and the Detroit Police Department, it began in the early morning hours of Sunday July 23, 1967, in Detroit, Michigan.

The history of Atlanta dates back to 1836, when Georgia decided to build a railroad to the U.S. Midwest and a location was chosen to be the line's terminus. The stake marking the founding of "Terminus" was driven into the ground in 1837. In 1839, homes and a store were built there and the settlement grew. Between 1845 and 1854, rail lines arrived from four different directions, and the rapidly growing town quickly became the rail hub for the entire Southern United States. During the American Civil War, Atlanta, as a distribution hub, became the target of a major Union campaign, and in 1864, Union William Sherman's troops set on fire and destroyed the city's assets and buildings, save churches and hospitals. After the war, the population grew rapidly, as did manufacturing, while the city retained its role as a rail hub. Coca-Cola was launched here in 1886 and grew into an Atlanta-based world empire. Electric streetcars arrived in 1889, and the city added new "streetcar suburbs".

John Hope, born in Augusta, Georgia, was an American educator and political activist, the first African-descended president of both Morehouse College in 1906 and of Atlanta University in 1929, where he worked to develop graduate programs. Both are historically Black colleges.

Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began on the evening of September 22, 1906, and lasted through September 24. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

The Commission on Interracial Cooperation (1918–1944) was an organization founded in Atlanta, Georgia, December 18, 1918, and officially incorporated in 1929. Will W. Alexander, pastor of a local white Methodist church, was head of the organization. It was formed in the aftermath of violent race riots that occurred in 1917 in several southern cities. In 1944 it merged with the Southern Regional Council.

Lugenia Burns Hope, was a social reformer whose Neighborhood Union and other community service organizations improved the quality of life for African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, and served as a model for the future Civil Rights Movement.

Floyd Bixler McKissick was an American lawyer and civil rights activist. He became the first African-American student at the University of North Carolina School of Law. In 1966 he became leader of CORE, the Congress of Racial Equality, taking over from James Farmer. A supporter of Black Power, he turned CORE into a more radical movement. In 1968, McKissick left CORE to found Soul City in Warren County, North Carolina. He endorsed Richard Nixon for president that year, and the federal government, under President Nixon, supported Soul City. He became a state district court judge in 1990 and died on April 28, 1991. He was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha fraternity.

African-American neighborhoods or black neighborhoods are types of ethnic enclaves found in many cities in the United States. Generally, an African American neighborhood is one where the majority of the people who live there are African American. Some of the earliest African-American neighborhoods were in New Orleans, Mobile, Atlanta, and other cities throughout the American South, as well as in New York City. In 1830, there were 14,000 "Free negroes" living in New York City.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

William Fitzhugh Brundage is an American historian, and William Umstead Distinguished Professor, at University of North Carolina. His works focus on white and black historical memory in the American South since the Civil War.

The Cincinnati Riots of 1836 were caused by racial tensions at a time when African Americans, some of whom had escaped from slavery in the Southern United States, were competing with whites for jobs. The racial riots occurred in Cincinnati, Ohio, United States in April and July 1836 by a mob of whites against black residents. These were part of a pattern of violence at that time. A severe riot had occurred in 1829, led by ethnic Irish, and another riot against blacks broke out in 1841. After the Cincinnati riots of 1829, in which many African Americans lost their homes and property, a growing number of whites, such as the "Lane rebels" who withdrew from the Cincinnati Lane Seminary en masse in 1834 over the issue of abolition, became sympathetic to their plight. The anti-abolitionist rioters of 1836, worried about their jobs if they had to compete with more blacks, attacked both the blacks and white supporters.

Jacqueline Anne Rouse (1950-2020) was an American scholar of African American women’s history. She is most widely known for her work on Southern black women and their activism from the turn of the twentieth century to the Civil Rights Movement.

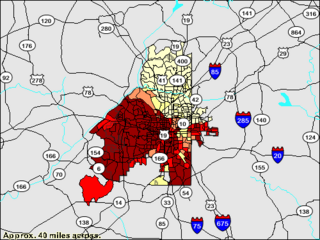

Black Atlantans are residents of the city Atlanta who are of African American ancestry. Atlanta has long been known as a center of black wealth, higher education, political power and culture; a cradle of the Civil Rights Movement and the home of Martin Luther King Jr. It has often been called a "black mecca". Atlanta is also home to many African and Caribbean immigrants. Atlanta’s black population is increasingly foreign-born.

In the United States, black genocide is the characterization that the mistreatment of African Americans by both the United States government and white Americans, both in the past and the present, amounts to genocide. The decades of lynchings and long-term racial discrimination were first formally described as genocide by a now defunct organization, the Civil Rights Congress, in a petition which it submitted to the United Nations in 1951. In the 1960s, Malcolm X accused the US government of engaging in genocide against black people, citing long-term injustice, cruelty, and violence against blacks by whites.

William Jefferson White was a civil rights leader, minister, educator, and journalist in Augusta, Georgia. He was the founder of Harmony Baptist Church in Augusta, Georgia in 1869 as well as other churches. He also was a co-founder of the Augusta Institute in 1867, which would become Morehouse College. He also helped found Atlanta University and was a trustee of both schools. He was a founder in 1880 and the managing editor of the Georgia Baptist, a leading African American newspaper for many years. He was an outspoken civil rights leader.

The Bogalusa saw mill killings was a racial attack that killed four labor organizers on November 22, 1919. It was mounted by the white paramilitary group the Self-Preservation and Loyalty League (SPLL) in Thibodaux, Louisiana. They were supported by the owners of Great Southern Lumber Company, a giant logging corporation, that hoped to prevent union organization and the Black and White labor organizations from merging.

Gregory Lamont Mixon is an American author and professor of history. He is the associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina Charlotte.

Atlanta's Berlin Wall, also known as the Peyton Road Affair or the Peyton Wall, refers to an event during the civil rights movement in Atlanta, Georgia, United States, in 1962. On December 17 of that year, the government of Atlanta, led by Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr., erected a barricade in the Cascade Heights neighborhood, mostly along Peyton Road, for the purposes of dissuading African Americans from moving into the neighborhood. The act was criticized by many African American leaders and civil rights groups in the city, and on March 1 of the following year the barricade was ruled unconstitutional and removed. The incident is seen as one of the most public examples of white Americans fears of racial integration in Atlanta.

Eugene Muse Mitchell was an American lawyer, politician, and historian. He served as the President of the Atlanta Board of Education from 1911 to 1912, during which time he eliminated the use of corporal punishment in city schools. He owned a law firm in Atlanta, and was a co-founder of the Atlanta Historical Society. He was married to the prominent Catholic activist and suffragist Maybelle Stephens Mitchell and was the father of Margaret Mitchell, who wrote the novel Gone With the Wind.

Georgia Baptist College was a private grade school and college in Macon, Georgia, United States. It was founded in 1899 as Central City College and was renamed in 1938. It closed due to financial difficulties in 1956.

References

- ↑ Friedman, Jean E. (1990). The Enclosed Garden: Women and Community in the Evangelical South, 1830-1900. UNC Press Books. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-8078-4281-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Mjagkij, Nina (2001). Organizing Black America: an encyclopedia of African American associations. Taylor & Francis. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-8153-2309-9.

- ↑ Godshalk, David Fort (2005). Veiled visions: the 1906 Atlanta race riot and the reshaping of American race relations. UNC Press. p. 210. ISBN 978-0-8078-5626-0.

- ↑ Rouse, Jacqueline Anne (1999). "The Atlanta Neighborhood Union, 1908-1924". In Paul D. Escott; David R. Goldfield; Sally Gregory McMillen (eds.). Major Problems in the History of the American South: The new South. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 271ff. ISBN 978-0-395-87140-9.

- 1 2 Lerner, Gerda; Linda K. Kerber (2005). The majority finds its past: placing women in history. UNC Press. pp. 68–69. ISBN 978-0-8078-5606-2 . Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Godshalk, David Fort (2005). Veiled visions: the 1906 Atlanta race riot and the reshaping of American race relations. UNC Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-8078-5626-0.

- 1 2 3 Tierney, Helen (1999). Women's studies encyclopedia, Volume 2. Greenwood. p. 604. ISBN 978-0-313-31072-0.

- 1 2 Neverdon-Morton, Cynthia (1997). "The Black Woman's Struggle for Equality in the South, 1895-1925". In Sharon Harley; Rosalyn Terborg-Penn (eds.). The Afro-American woman: struggles and images. Black Classic Press. pp. 43–57. ISBN 978-1-57478-026-0 . Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ↑ Ferguson, Karen Jane (2002). Black politics in New Deal Atlanta. UNC Press. pp. 49–51. ISBN 978-0-8078-5370-2.

- ↑ Ferguson 279.

- ↑ Scott, Anne Firor (1990). "Most Invisible of All: Black Women's Voluntary Associations". The Journal of Southern History . 56 (1): 3–22. doi:10.2307/2210662.

- ↑ Godshalk, David Fort (2005). Veiled visions: the 1906 Atlanta race riot and the reshaping of American race relations. UNC Press. p. 315. ISBN 978-0-8078-5626-0.