Related Research Articles

The Ku Klux Klan, commonly shortened to the KKK or the Klan, is the name of several historical and current American white supremacist, far-right terrorist organizations and hate groups. According to historian Fergus Bordewich, the Klan was "the first organized terror movement in American history." Their primary targets, at various times and places, have been African Americans, Jews, and Catholics.

Harrison County is a county on the eastern border of the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2020 United States census, its population was 68,839. The county seat is Marshall. The county was created in 1839 and organized in 1842. It is named for Jonas Harrison, a lawyer and Texas revolutionary.

Rebecca Ann Felton was an American writer, politician, and slave owner who was the first woman to serve in the United States Senate, serving for only one day. She was a prominent member of the Georgia upper class who advocated for prison reform, women's suffrage and education reform. Her husband, William Harrell Felton, served in both the United States House of Representatives and the Georgia House of Representatives, and she helped organize his political campaigns. Historian Numan Bartley wrote that by 1915 Felton "was championing a lengthy feminist program that ranged from prohibition to equal pay for equal work yet never accomplished any feat because she held her role because of her husband."

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett was an American investigative journalist, educator, and early leader in the civil rights movement. She was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Wells dedicated her career to combating prejudice and violence, and advocating for African-American equality—especially that of women.

The civil rights movement (1896–1954) was a long, primarily nonviolent action to bring full civil rights and equality under the law to all Americans. The era has had a lasting impact on American society – in its tactics, the increased social and legal acceptance of civil rights, and in its exposure of the prevalence and cost of racism.

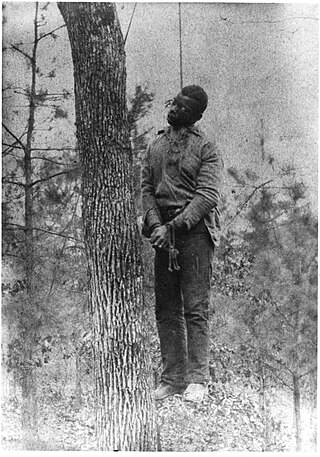

Lynching was the widespread occurrence of extrajudicial killings which began in the United States' pre–Civil War South in the 1830s and ended during the civil rights movement in the 1950s and 1960s. Although the victims of lynchings were members of various ethnicities, after roughly 4 million enslaved African Americans were emancipated, they became the primary targets of white Southerners. Lynchings in the U.S. reached their height from the 1890s to the 1920s, and they primarily victimized ethnic minorities. Most of the lynchings occurred in the American South, as the majority of African Americans lived there, but racially motivated lynchings also occurred in the Midwest and border states. In 1891, the largest single mass lynching in American history was perpetrated in New Orleans against Italian immigrants.

Jesse Washington was a seventeen-year-old African American farmhand who was lynched in the county seat of Waco, Texas, on May 15, 1916, in what became a well-known example of lynching. Washington was convicted of raping and murdering Lucy Fryer, the wife of his white employer in rural Robinson, Texas. He was chained by his neck and dragged out of the county court by observers. He was then paraded through the street, all while being stabbed and beaten, before being held down and castrated. He was then lynched in front of Waco's city hall.

The 1906 Atlanta Race Massacre, also known as the 1906 Atlanta Race Riot, was an episode of mass racial violence against African Americans in the United States in September 1906. Violent attacks by armed mobs of White Americans against African Americans in Atlanta, Georgia, began after newspapers, on the evening of September 22, 1906, published several unsubstantiated and luridly detailed reports of the alleged rapes of 4 local women by black men. The violence lasted through September 24, 1906. The events were reported by newspapers around the world, including the French Le Petit Journal which described the "lynchings in the USA" and the "massacre of Negroes in Atlanta," the Scottish Aberdeen Press & Journal under the headline "Race Riots in Georgia," and the London Evening Standard under the headlines "Anti-Negro Riots" and "Outrages in Georgia." The final death toll of the conflict is unknown and disputed, but officially at least 25 African Americans and two whites died. Unofficial reports ranged from 10–100 black Americans killed during the massacre. According to the Atlanta History Center, some black Americans were hanged from lampposts; others were shot, beaten or stabbed to death. They were pulled from street cars and attacked on the street; white mobs invaded black neighborhoods, destroying homes and businesses.

The Commission on Interracial Cooperation (1918–1944) was an organization founded in Atlanta, Georgia, December 18, 1918, and officially incorporated in 1929. Will W. Alexander, pastor of a local white Methodist church, was head of the organization. It was formed in the aftermath of violent race riots that occurred in 1917 in several southern cities. In 1944 it merged with the Southern Regional Council.

Hatton William Sumners was a Democratic Congressman from the Dallas, Texas, area, serving from 1913 to 1947. He rose to become Chairman of the powerful House Judiciary Committee.

Jessie Daniel Ames was a suffragist and civil rights leader from Texas who helped create the anti-lynching movement in the American South. She was one of the first Southern white women to speak out and work publicly against lynching of African Americans, murders which white men claimed to commit in an effort to protect women's "virtue." Despite risks to her personal safety, Ames stood up to these men and led organized efforts by white women to protest lynchings. She gained 40,000 signatures of Southern white women to oppose lynching, helping change attitudes and bring about a decline in these murders in the 1930s and 1940s.

The civil rights movement (1865–1896) aimed to eliminate racial discrimination against African Americans, improve their educational and employment opportunities, and establish their electoral power, just after the abolition of slavery in the United States. The period from 1865 to 1895 saw a tremendous change in the fortunes of the Black community following the elimination of slavery in the South.

Daisy Elizabeth Adams Lampkin was an American suffragist, civil rights activist, organization executive, and community practitioner whose career spanned over half a century. Lampkin’s effective skills as an orator, fundraiser, organizer, and political activist guided the work being conducted by the National Association of Colored Women (NACW); National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); National Council of Negro Women and other leading civil rights organizations of the Progressive Era.

Jacquelyn Dowd Hall is an American historian and Julia Cherry Spruill Professor Emerita at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her scholarship and teaching forwarded the emergence of U.S. women's history in the 1960s and 1970s, helped to inspire new research on Southern labor history and the long civil rights movement, and encouraged the use of oral history sources in historical research. She is the author of Revolt Against Chivalry: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women’s Campaign Against Lynching;Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World and Sisters and Rebels: The Struggle for the Soul of America.

The Phoenix election riot occurred on November 8, 1898, near Greenwood County, South Carolina, when a group of local white Democrats attempted to stop a Republican election official from taking the affidavits of African Americans who had been denied the ability to vote. The race-based riot was part of numerous efforts by white conservative Democrats to suppress voting by blacks, as they had largely supported the Republican Party since the Reconstruction era. Beginning with Mississippi in 1890, and South Carolina in 1895, southern states were passing new constitutions and laws designed to disenfranchise blacks by making voter registration and voting more difficult.

In Forsyth County, Georgia, in September 1912, two separate alleged attacks on white women in the Cumming area resulted in black men being accused as suspects. First, a white woman reportedly awoke to find a black man in her bedroom; then days later, a white teenage girl was beaten and raped, later dying of her injuries.

Press Women of Texas (PWT) is an association of Texas women journalists which was founded in 1893. PWT is an affiliate of the National Federation of Press Women (NFPW). PWT was involved in more than just supporting women in journalism; the organization advocated many causes, including education, preservation of library and archive materials and supporting scholarships. They also supported women's suffrage in Texas in 1915. Angela Smith is the current president of PWT.

Austin Callaway, also known as Austin Brown, was a young African-American man who was taken from jail by a group of six white men and lynched on September 8, 1940, in LaGrange, Georgia. The day before, Callaway had been arrested as a suspect in an assault of a white woman. The gang carried out extrajudicial punishment and prevented the youth from ever receiving a trial. They shot him numerous times, fatally wounding him and leaving him for dead. Found by a motorist, Callaway was taken to a hospital, where he died of his wounds.

Josephine Mathewson Wilkins was an American social activist, president of the Georgia State League of Women Voters. She is a 2022 inductee into the Georgia Women of Achievement.

The lynching of George Hughes, which led to what is called the Sherman Riot, took place in Sherman, Texas, in 1930. An African-American man accused of rape and who was tried in court died on May 9 when the Grayson County Courthouse was set on fire by a White mob, who subsequently burned and looted local Black-owned businesses. Martial law was declared on May 10, but by that time many of Sherman's Black-owned businesses had been burnt to the ground. Thirty-nine people were arrested, eight of whom were charged, and later, a grand jury indicted 14 men, none for lynching. By October 1931, one man received a short prison term for arson and inciting a riot. The outbreak of violence was followed by two more lynchings in Texas, one in Oklahoma, and several lynching attempts.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nancy Baker Jones, ASSOCIATION OF SOUTHERN WOMEN FOR THE PREVENTION OF LYNCHING, Handbook of Texas Online. Uploaded on June 9, 2010. Published by the Texas State Historical Association.

- ↑ Barnes, Rhae Lynn. "A Man Was Lynched Yesterday". U.S. History Scene. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Spearman, Walter (27 May 1979). "The Literary Lantern" . Burlington Daily Times News. Retrieved 24 December 2015– via Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ McGovern, James R. (1982). Anatomy of a Lynching: The Killing of Claude Neal (Updated ed.). Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 9780807154274.

- ↑ Aaronson, Ely (2014). From Slave Abuse to Hate Crime: The Criminalization of Racial Violence in American History. Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 9781107026896.

- ↑ Mwamba, Jay (6 February 2015). "Black History Month 2015: Grim Struggle to End the Nightmare of Lynching". New York Daily News. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ↑ Freedman, Estelle B. (2013). Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674724846.

- 1 2 Barber, Henry E. (1994). "The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, 1930-1942". In Cott, Nancy F. (ed.). History of Women in the United States: Social and Moral Reform. Part 2. Vol. 17. Munich: Die Deutsche Bibliothek. pp. 635–636. ISBN 3598416954.

- 1 2 3 4 Barber, Henry E. (1973-12-01). "The Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, 1930-1942". Phylon. 34 (4): 378–389. doi:10.2307/274253. JSTOR 274253.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Dykeman, Wilma; Stokely, James (November 1957). "The Plight of Southern White Women" . Ebony. 13 (1): 32–42. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- 1 2 Wormser, Richard (2002). "Jessie Daniel Ames". Jim Crow Stories. PBS. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Hall, Jacquelyn (8 March 2013). "From the Southern Exposure Archives: Women and Lynching". Facing South. The Institute for Southern Studies. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 O'Dea Schenken, Suzanne (1999). From Suffrage to the Senate: An Encyclopedia of American Women in Politics. Vol. 1. ABC-CLIO. pp. 45–46. ISBN 0874369606.

- 1 2 3 "South Completes a Year Without Lynching" . Hattiesburg American. 10 May 1940. Retrieved 24 December 2015– via Newspaper Archive.

- 1 2 "Seek to End Lynching" . Madison Wisconsin State Journal. 17 May 1940. Retrieved 24 December 2015– via Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ Arneson, Pat (2014). "Jessie Daniel Ames". Communicative Engagement and Social Liberation: Justice Will Be Made. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9781611476514.

- ↑ Markovitz, Jonathan (2004). Legacies of Lynching: Racial Violence and Memory . University of Minnesota Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 0816639949.

Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching.

- ↑ "Southern Women May Try News Reporting In Fresh Attempt To Stamp Out Lynching" . Corpus Christi Times. 2 February 1940. Retrieved 24 December 2015– via Newspaper Archive.

- ↑ "Blytheville Courier News" . Women Demand Inquiry Into Lepanto Lynching. 5 May 1936. Retrieved 23 December 2015– via Newspaper Archive.