A pidgin, or pidgin language, is a grammatically simplified means of communication that develops between two or more groups of people that do not have a language in common: typically, its vocabulary and grammar are limited and often drawn from several languages. It is most commonly employed in situations such as trade, or where both groups speak languages different from the language of the country in which they reside. Linguists do not typically consider pidgins as full or complete languages.

Linguistic typology is a field of linguistics that studies and classifies languages according to their structural features to allow mass comparisons of the cross-linguistic data. Its aim is to describe and explain the structural diversity and the common properties of the world's languages. Its subdisciplines include, but are not limited to phonological typology, which deals with sound features; syntactic typology, which deals with word order and form; lexical typology, which deals with language vocabulary; and theoretical typology, which aims to explain the universal tendencies.

A creole language, or simply creole, is a stable natural language that develops from the simplifying and mixing of different languages into a new one within a fairly brief period of time: often, a pidgin evolved into a full-fledged language. While the concept is similar to that of a mixed or hybrid language, creoles are often characterized by a tendency to systematize their inherited grammar. Like any language, creoles are characterized by a consistent system of grammar, possess large stable vocabularies, and are acquired by children as their native language. These three features distinguish a creole language from a pidgin. Creolistics, or creology, is the study of creole languages and, as such, is a subfield of linguistics. Someone who engages in this study is called a creolist.

Norfuk or Norf'k is the language spoken on Norfolk Island by the local residents. It is a blend of 18th-century English and Tahitian, originally introduced by Pitkern-speaking settlers from the Pitcairn Islands. Along with English, it is the co-official language of Norfolk Island.

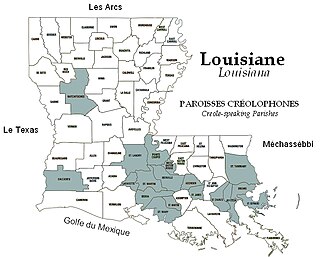

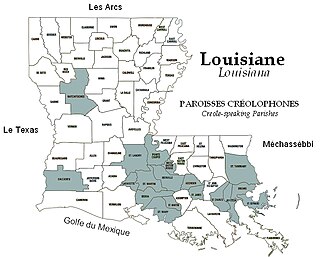

Louisiana Creole is a French-based creole language spoken by fewer than 10,000 people, mostly in the state of Louisiana. It is spoken today by people who racially identify as White, Black, mixed, and Native American, as well as Cajun and Louisiana Creole. It should not be confused with its sister language, Louisiana French, a dialect of the French language.

A mixed language is a language that arises among a bilingual group combining aspects of two or more languages but not clearly deriving primarily from any single language. It differs from a creole or pidgin language in that, whereas creoles/pidgins arise where speakers of many languages acquire a common language, a mixed language typically arises in a population that is fluent in both of the source languages.

Unserdeutsch, or Rabaul Creole German, is a German-based creole language that originated in Papua New Guinea as a lingua franca. The substrate language is assumed to be Tok Pisin, while the majority of the lexicon is from German.

Belizean Creole is an English-based creole language spoken by the Belizean Creole people. It is closely related to Miskito Coastal Creole, San Andrés-Providencia Creole, and Jamaican Patois.

The subject-side parameter, also called the specifier–head parameter, is a proposed parameter within generative linguistics which states that the position of the subject may precede or follow the head. In the world's languages, Specifier-first order is more common than Specifier-final order. For example, in the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures (WALS), 76% of the languages in their sample Specifier-first. In this respect, the subject-side parameter contrasts with the head-directionality parameter. The latter, which classifies languages according to whether the head precedes or follows its complement, shows a roughly 50-50 split: in languages that have a fixed word order, about half have a Head-Complement order, and half have a Complement-Head order.

Juba Arabic, also known since 2011 as South Sudanese Arabic, is a lingua franca spoken mainly in Equatoria Province in South Sudan, and derives its name from the South Sudanese capital, Juba. It is also spoken among communities of people from South Sudan living in towns in Sudan. The pidgin developed in the 19th century, among descendants of Sudanese soldiers, many of whom were recruited from southern Sudan. Residents of other large towns in South Sudan, notably Malakal and Wau, do not generally speak Juba Arabic, tending towards the use of Arabic closer to Sudanese Arabic, in addition to local languages. Reportedly, it is the most spoken language in South Sudan despite government attempts to discourage its use due to its association with past Arab colonization.

Gurindji Kriol is a mixed language which is spoken by Gurindji people in the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory (Australia). It is mostly spoken at Kalkaringi and Daguragu which are Aboriginal communities located on the traditional lands of the Gurindji. Related mixed varieties are spoken to the north by Ngarinyman and Bilinarra people at Yarralin and Pigeon Hole. These varieties are similar to Gurindji Kriol, but draw on Ngarinyman and Bilinarra which are closely related to Gurindji.

The language bioprogram theory or language bioprogram hypothesis (LBH) is a theory arguing that the structural similarities between different creole languages cannot be solely attributed to their superstrate and substrate languages. As articulated mostly by Derek Bickerton, creolization occurs when the linguistic exposure of children in a community consists solely of a highly unstructured pidgin; these children use their innate language capacity to transform the pidgin, which characteristically has high syntactic variability, into a language with a highly structured grammar. As this capacity is universal, the grammars of these new languages have many similarities.

Sri Lankan Malay is a creole language spoken in Sri Lanka, formed as a mixture of Sinhala and Shonam, with Malay being the major lexifier. It is traditionally spoken by the Sri Lankan Malays and among some Sinhalese in Hambantota. Today, the number of speakers of the language have dwindled considerably but it has continued to be spoken notably in the Hambantota District of Southern Sri Lanka, which has traditionally been home to many Sri Lankan Malays.

Pichinglis, commonly referred to by its speakers as Pichi and formally known as Fernando Po Creole English (Fernandino), is an Atlantic English-lexicon creole language spoken on the island of Bioko, Equatorial Guinea. It is an offshoot of the Krio language of Sierra Leone, and was brought to Bioko by Krios who immigrated to the island during the colonial era in the 19th century.

Ghanaian Pidgin English (GhaPE), is a Ghanaian English-lexifier pidgin also known as Pidgin, Broken English, and Kru English. GhaPE is a regional variety of West African Pidgin English spoken in Ghana, predominantly in the southern capital, Accra, and surrounding towns. It is confined to a smaller section of society than other West African creoles, and is more stigmatized, perhaps due to the importance of Twi, an Akan dialect, often spoken as lingua franca. Other languages spoken as lingua franca in Ghana are Standard Ghanaian English (SGE) and Akan. GhaPE cannot be considered a creole as it has no L1 speakers.

Susanne Maria Michaelis is a specialist in creole linguistics who is affiliated with the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. She was previously at Leipzig University and at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History in Jena.

The Cross-Linguistic Linked Data (CLLD) project coordinates over a dozen linguistics databases covering the languages of the world. It is hosted by the Department of Linguistic and Cultural Evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

William John Samarin was an American-born linguist and academic who was Professor at the Hartford Seminary and the University of Toronto. He is best known for his work on the language of religion, on the two central African languages Sango and Gbeya, on pidginization, and on ideophones in African languages.

Annegret Bollée was a German linguist and Professor Emeritus at the University of Bamberg, specializing in Romance linguistics and creole languages.

In linguistic typology, object–subject (OS) word order, also called O-before-S or patient–agent word order, is a word order in which the object appears before the subject. OS is notable for its statistical rarity as a default or predominant word order among natural languages. Languages with predominant OS word order display properties that distinguish them from languages with subject–object (SO) word order.