Atomism or social atomism is a sociological theory arising from the scientific notion atomic theory , coined by the ancient Greek philosopher Democritus and the Roman philosopher Lucretius. In the scientific rendering of the word, atomism refers to the notion that all matter in the universe is composed of basic indivisible components, or atoms. When placed into the field of sociology, atomism assigns the individual as the basic unit of analysis for all implications of social life. [1] This theory refers to "the tendency for society to be made up of a collection of self-interested and largely self-sufficient individuals, operating as separate atoms." [2] Therefore, all social values, institutions, developments and procedures evolve entirely out of the interests and actions of the individuals who inhabit any particular society. The individual is the "atom" of society and therefore the only true object of concern and analysis. [3]

Political theorists such as John Locke and Thomas Hobbes extend social atomism to the political realm. They assert that human beings are fundamentally self-interested, equal, and rational social atoms that together form an aggregate society of self-interested individuals. Those participating in society must sacrifice a portion of their individual rights in order to form a social contract with the other persons in society. Ultimately, although some rights are renounced, self-interested cooperation occurs for the mutual preservation of the individuals and for society at large. [4]

According to the philosopher Charles Taylor,

The term "atomism" is used loosely to characterize the doctrines of social contract theory which arose in the seventeenth century and also successor doctrines which may not have made use of the concept of social contract but which inherited a vision of society as in some sense constituted by individuals for the fulfilment of ends which were primarily individual. Certain forms of utilitarianism are successor doctrines in this sense. The term is also applied to contemporary doctrines which hark back to social contract theory, or which try to defend in some sense the priority of the individual and his rights over society, or which present a purely instrumental view of society. [5]

Those who criticize the theory of social atomism believe that it neglects the idea of the individual as unique. The sociologist Elizabeth Wolgast asserts that,

From the atomistic standpoint, the individuals who make up a society are interchangeable like molecules in a bucket of water – society a mere aggregate of individuals. This introduces a harsh and brutal equality into our theory of human life and it contradicts our experience of human beings as unique and irreplaceable, valuable in virtue of their variety – in what they don't share – not in virtue of their common ability to reason. [6]

Those who question social atomism argue that it is unjust to treat all persons equally when individual necessities and circumstances are clearly dissimilar. [7]

In ethical philosophy, ethical egoism is the normative position that moral agents ought to act in their own self-interest. It differs from psychological egoism, which claims that people can only act in their self-interest. Ethical egoism also differs from rational egoism, which holds that it is rational to act in one's self-interest. Ethical egoism holds, therefore, that actions whose consequences will benefit the doer are ethical.

Egoism is a philosophy concerned with the role of the self, or ego, as the motivation and goal of one's own action. Different theories of egoism encompass a range of disparate ideas and can generally be categorized into descriptive or normative forms. That is, they may be interested in either describing that people do act in self-interest or prescribing that they should. Other definitions of egoism may instead emphasise action according to one's will rather than one's self-interest, and furthermore posit that this is a truer sense of egoism.

Egalitarianism, or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds from the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all humans are equal in fundamental worth or moral status. Egalitarianism is the doctrine that all citizens of a state should be accorded to exactly equal rights.

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and provide a deeper understanding of legal reasoning and analogy, legal systems, legal institutions, and the proper application and role of law in society.

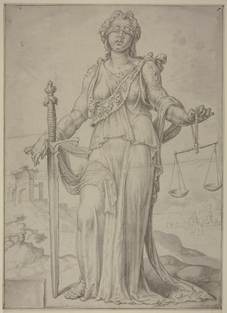

Justice, in its broadest sense, is the principle that people receive that which they deserve, with the interpretation of what then constitutes "deserving" being impacted upon by numerous fields, with many differing viewpoints and perspectives, including the concepts of moral correctness based on ethics, rationality, law, religion, equity and fairness. The state will sometimes endeavour to increase justice by operating courts and enforcing their rulings.

Philosophy of law is a branch of philosophy that examines the nature of law and law's relationship to other systems of norms, especially ethics and political philosophy. It asks questions like "What is law?", "What are the criteria for legal validity?", and "What is the relationship between law and morality?" Philosophy of law and jurisprudence are often used interchangeably, though jurisprudence sometimes encompasses forms of reasoning that fit into economics or sociology.

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is a theory or model that originated during the Age of Enlightenment and usually concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual.

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. Following pioneering work by Michel Foucault, these fields view discourse as a system of thought, knowledge, or communication that constructs our experience of the world. Since control of discourse amounts to control of how the world is perceived, social theory often studies discourse as a window into power. Within theoretical linguistics, discourse is understood more narrowly as linguistic information exchange and was one of the major motivations for the framework of dynamic semantics, in which expressions' denotations are equated with their ability to update a discourse context.

Determinism is a philosophical view where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. The opposite of determinism is some kind of indeterminism or randomness. Determinism is often contrasted with free will, although some philosophers claim that the two are compatible.

Social justice is justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. In Western and Asian cultures, the concept of social justice has often referred to the process of ensuring that individuals fulfill their societal roles and receive their due from society. In the current movements for social justice, the emphasis has been on the breaking of barriers for social mobility, the creation of safety nets, and economic justice. Social justice assigns rights and duties in the institutions of society, which enables people to receive the basic benefits and burdens of cooperation. The relevant institutions often include taxation, social insurance, public health, public school, public services, labor law and regulation of markets, to ensure distribution of wealth, and equal opportunity.

Virtue ethics is an approach to ethics that treats the concept of moral virtue as central. Virtue ethics is usually contrasted with two other major approaches in normative ethics, consequentialism and deontology, which make the goodness of outcomes of an action (consequentialism) and the concept of moral duty (deontology) central. While virtue ethics does not necessarily deny the importance of goodness of states of affairs or moral duties to ethics, it emphasizes moral virtue, and sometimes other concepts, like eudaimonia, to an extent that other normative ethical dispositions do not.

Natural rights and legal rights are two types of rights.

Positive liberty is the possession of the power and resources to act in the context of the structural limitations of the broader society which impacts a person's ability to act, as opposed to negative liberty, which is freedom from external restraint on one's actions.

Negative liberty is freedom from interference by other people. Negative liberty is primarily concerned with freedom from external restraint and contrasts with positive liberty. The distinction was introduced by Isaiah Berlin in his 1958 lecture "Two Concepts of Liberty".

Solidarity is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. It is based on class collaboration. It refers to the ties in a society that bind people together as one. The term is generally employed in sociology and the other social sciences as well as in philosophy and bioethics. It is also a significant concept in Catholic social teaching; therefore it is a core concept in Christian democratic political ideology.

Platonism is the philosophy of Plato and philosophical systems closely derived from it, though contemporary platonists do not necessarily accept all of the doctrines of Plato. Platonism had a profound effect on Western thought. Platonism at least affirms the existence of abstract objects, which are asserted to exist in a third realm distinct from both the sensible external world and from the internal world of consciousness, and is the opposite of nominalism. This can apply to properties, types, propositions, meanings, numbers, sets, truth values, and so on. Philosophers who affirm the existence of abstract objects are sometimes called platonists; those who deny their existence are sometimes called nominalists. The terms "platonism" and "nominalism" also have established senses in the history of philosophy. They denote positions that have little to do with the modern notion of an abstract object.

This glossary of philosophy is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to philosophy and related disciplines, including logic, ethics, and theology.

Rational egoism is the principle that an action is rational if and only if it maximizes one's self-interest. As such, it is considered a normative form of egoism, though historically has been associated with both positive and normative forms. In its strong form, rational egoism holds that to not pursue one's own interest is unequivocally irrational. Its weaker form, however, holds that while it is rational to pursue self-interest, failing to pursue self-interest is not always irrational.

An individual is that which exists as a distinct entity. Individuality is the state or quality of being an individual; particularly of being a person unique from other people and possessing one's own needs or goals, rights and responsibilities. The concept of an individual features in diverse fields, including biology, law, and philosophy.

The philosophy of human rights attempts to examine the underlying basis of the concept of human rights and critically looks at its content and justification. Several theoretical approaches have been advanced to explain how and why the concept of human rights developed.