In ethical philosophy, consequentialism is a class of normative, teleological ethical theories that holds that the consequences of one's conduct are the ultimate basis for judgement about the rightness or wrongness of that conduct. Thus, from a consequentialist standpoint, a morally right act is one that will produce a good outcome. Consequentialism, along with eudaimonism, falls under the broader category of teleological ethics, a group of views which claim that the moral value of any act consists in its tendency to produce things of intrinsic value. Consequentialists hold in general that an act is right if and only if the act will produce, will probably produce, or is intended to produce, a greater balance of good over evil than any available alternative. Different consequentialist theories differ in how they define moral goods, with chief candidates including pleasure, the absence of pain, the satisfaction of one's preferences, and broader notions of the "general good".

Hedonism refers to a family of theories, all of which have in common that pleasure plays a central role in them. Psychological or motivational hedonism claims that human behavior is determined by desires to increase pleasure and to decrease pain. Normative or ethical hedonism, on the other hand, is not about how humans actually act but how humans should act: people should pursue pleasure and avoid pain. Axiological hedonism, which is sometimes treated as a part of ethical hedonism, is the thesis that only pleasure has intrinsic value. Applied to well-being or what is good for someone, it is the thesis that pleasure and suffering are the only components of well-being. These technical definitions of hedonism within philosophy, which are usually seen as respectable schools of thought, have to be distinguished from how the term is used in "everyday language". In that sense, it has a negative connotation, linked to the egoistic pursuit of short-term gratification by indulging in sensory pleasures without regard for the consequences.

Normative ethics is the study of ethical behaviour and is the branch of philosophical ethics that investigates questions regarding how one ought to act, in a moral sense.

In ethical philosophy, utilitarianism is a family of normative ethical theories that prescribe actions that maximize happiness and well-being for all affected individuals.

Derek Antony Parfit was a British philosopher who specialised in personal identity, rationality, and ethics. He is widely considered one of the most important and influential moral philosophers of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

In ethics, welfarism is a theory that well-being, what is good for someone or what makes a life worth living, is the only thing that has intrinsic value. In its most general sense, it can be defined as descriptive theory about what has value, but some philosophers also understand welfarism as a moral theory, that what one should do is ultimately determined by considerations of well-being. The right action, policy or rule is the one leading to the maximal amount of well-being. In this sense, it is often seen as a type of consequentialism, and can take the form of utilitarianism.

The mere addition paradox is a problem in ethics identified by Derek Parfit and discussed in his book Reasons and Persons (1984). The paradox identifies the mutual incompatibility of four intuitively compelling assertions about the relative value of populations. Parfit’s original formulation of the repugnant conclusion is that “For any perfectly equal population with very high positive welfare, there is a population with very low positive welfare which is better, other things being equal.”

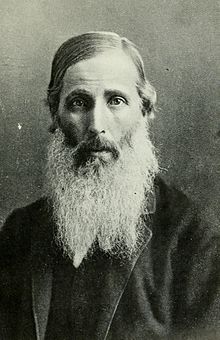

John Stuart Mill's book Utilitarianism is a classic exposition and defence of utilitarianism in ethics. The essay first appeared as a series of three articles published in Fraser's Magazine in 1861 ; the articles were collected and reprinted as a single book in 1863. Mill's aim in the book is to explain what utilitarianism is, to show why it is the best theory of ethics, and to defend it against a wide range of criticisms and misunderstandings. Though heavily criticized both in Mill's lifetime and in the years since, Utilitarianism did a great deal to popularize utilitarian ethics and has been considered "the most influential philosophical articulation of a liberal humanistic morality that was produced in the nineteenth century."

Rational egoism is the principle that an action is rational if and only if it maximizes one's self-interest. As such, it is considered a normative form of egoism, though historically has been associated with both positive and normative forms. In its strong form, rational egoism holds that to not pursue one's own interest is unequivocally irrational. Its weaker form, however, holds that while it is rational to pursue self-interest, failing to pursue self-interest is not always irrational.

Act utilitarianism is a utilitarian theory of ethics that states that a person's act is morally right if and only if it produces the best possible results in that specific situation. Classical utilitarians, including Jeremy Bentham, John Stuart Mill, and Henry Sidgwick, define happiness as pleasure and the absence of pain.

The utility monster is a thought experiment in the study of ethics created by philosopher Robert Nozick in 1974 as a criticism of utilitarianism.

Two-level utilitarianism is a utilitarian theory of ethics developed by R. M. Hare. According to the theory, a person's moral decisions should be based on a set of moral rules, except in certain rare situations where it is more appropriate to engage in a 'critical' level of moral reasoning.

Population ethics is the philosophical study of the ethical problems arising when our actions affect who is born and how many people are born in the future. An important area within population ethics is population axiology, which is "the study of the conditions under which one state of affairs is better than another, when the states of affairs in question may differ over the numbers and the identities of the persons who ever live."

Prioritarianism, also known as the priority view, stands as a vantage point within the realms of ethics and political philosophy asserting that "social welfare orderings should give explicit priority to the worse off". This viewpoint shares similarities with utilitarianism. Like utilitarianism, prioritarianism aligns with aggregative consequentialism; nonetheless, it varies by assigning differential weight to the well-being of individuals, giving priority to those who are in more unfavourable circumstances.

The Methods of Ethics is a book on ethics first published in 1874 by the English philosopher Henry Sidgwick. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy indicates that The Methods of Ethics "in many ways marked the culmination of the classical utilitarian tradition." Noted moral and political philosopher John Rawls, writing in the Forward to the Hackett reprint of the 7th edition, says Methods of Ethics "is the clearest and most accessible formulation of ... 'the classical utilitarian doctrine'". Contemporary utilitarian philosopher Peter Singer has said that the Methods "is simply the best book on ethics ever written."

Larry Temkin is an American philosopher specializing in normative ethics and political philosophy. His research into equality, practical reason, and the nature of the good has been very influential. His work on the intransitivity of the "all things considered better than"-relation is groundbreaking and challenges deeply held assumptions about value, practical reasoning, and the goodness of outcomes. His 1993 book Inequality was described by the Times Literary Supplement as "brilliant and fascinating," and as offering the reader more than any other book on the same subject.

Negative utilitarianism is a form of negative consequentialism that can be described as the view that people should minimize the total amount of aggregate suffering, or that they should minimize suffering and then, secondarily, maximize the total amount of happiness. It can be considered as a version of utilitarianism that gives greater priority to reducing suffering than to increasing pleasure. This differs from classical utilitarianism, which does not claim that reducing suffering is intrinsically more important than increasing happiness. Both versions of utilitarianism hold that morally right and morally wrong actions depend solely on the consequences for overall aggregate well-being. "Well-being" refers to the state of the individual.

A person-affecting or person-based view in population ethics captures the intuition that an act can only be bad if it is bad for someone. Similarly something can be good only if it is good for someone. Therefore, according to standard person-affecting views, there is no moral obligation to create people nor moral good in creating people because nonexistence means "there is never a person who could have benefited from being created". Whether one accepts person-affecting views greatly influences to what extent shaping the far future is important if there are more potential humans in the future. Person-affecting views are also important in considering human population control.

The Asymmetry, also known as 'the Procreation Asymmetry', is the idea in population ethics that there is a moral or evaluative asymmetry between bringing into existence individuals with good or bad lives. It was first discussed by Jan Narveson in 1967, and Jeff McMahan coined the term 'the Asymmetry' in 1981. McMahan formulates the Asymmetry as follows: "while the fact that a person's life would be worse than no life at all ... constitutes a strong moral reason for not bringing him into existence, the fact that a person's life would be worth living provides no moral reason for bringing him into existence." Professor Nils Holtug formulates the Asymmetry evaluatively in terms of the value of outcomes instead of in terms of moral reasons. Holtug's formulation says that "while it detracts from the value of an outcome to add individuals whose lives are of overall negative value, it does not increase the value of an outcome to add individuals whose lives are of overall positive value."

Katarzyna de Lazari-Radek is a Polish utilitarian philosopher and an assistant professor at the Institute of Philosophy at University of Łódź.