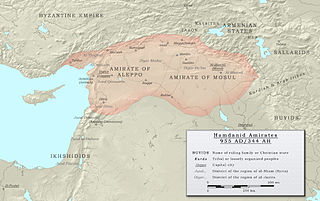

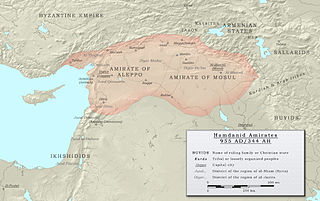

The Hamdanid dynasty was a Shia Muslim Arab dynasty of Northern Mesopotamia and Syria (890–1004). They descended from the ancient Banu Taghlib tribe of Mesopotamia and Arabia.

Abu Mansur Nizar, known by his regnal name as al-Aziz Billah, was the fifth caliph of the Fatimid dynasty, from 975 to his death in 996. His reign saw the capture of Damascus and the Fatimid expansion into the Levant, which brought al-Aziz into conflict with the Byzantine emperor Basil II over control of Aleppo. During the course of this expansion, al-Aziz took into his service large numbers of Turkic and Daylamite slave-soldiers, thereby breaking the near-monopoly on Fatimid military power held until then by the Kutama Berbers.

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Ṭughj ibn Juff ibn Yiltakīn ibn Fūrān ibn Fūrī ibn Khāqān, better known by the title al-Ikhshīd after 939, was an Abbasid commander and governor who became the autonomous ruler of Egypt and parts of Syria (Levant) from 935 until his death in 946. He was the founder of the Ikhshidid dynasty, which ruled the region until the Fatimid conquest of 969.

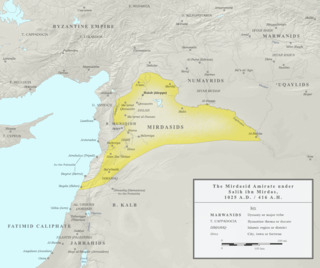

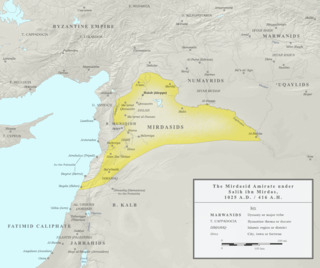

Abu Ali Salih ibn Mirdas, also known by his laqabAsad al-Dawla, was the founder of the Mirdasid dynasty and emir of Aleppo from 1025 until his death in May 1029. At its peak, his emirate (principality) encompassed much of the western Jazira, northern Syria and several central Syrian towns. With occasional interruption, Salih's descendants ruled Aleppo for the next five decades.

The Mirdasid dynasty, also called the Banu Mirdas, was an Arab Shia Muslim dynasty which ruled an Aleppo-based emirate in northern Syria and the western Jazira more or less continuously from 1024 until 1080.

ʿAlī ibn ʾAbū'l-Hayjāʾ ʿAbdallāh ibn Ḥamdān ibn Ḥamdūn ibn al-Ḥārith al-Taghlibī, more commonly known simply by his honorific of Sayf al-Dawla, was the founder of the Emirate of Aleppo, encompassing most of northern Syria and parts of the western Jazira.

Manjutakin was a military slave (ghulam) of the Fatimid Caliph al-Aziz. Of Turkic origin, he became one of the leading Fatimid generals under al-Aziz, fighting against the Hamdanids and the Byzantines in Syria. He rebelled against the Berber-dominated regime of the early years of al-Hakim, but was defeated and died in captivity.

Abu Muhammad Lu'lu', surnamed al-Kabir and al-Jarrahi al-Sayfi, was a military slave (ghulam) of the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo. Under the rule of Sa'd al-Dawla, he rose to become the emirate's chamberlain, and on Sa'd al-Dawla's death in 991 he was appointed guardian of his son and successor, Sa'id al-Dawla. The able Lu'lu' soon became the de facto ruler of the emirate, securing his position by marrying his daughter to the young emir. His perseverance and aid from the Byzantine emperor Basil II preserved Aleppo from repeated Fatimid attempts to conquer it. Upon Sa'id al-Dawla's death in 1002—possibly poisoned by Lu'lu'—he became the ruler of the emirate, disinheriting Sa'id al-Dawla's sons. He ruled with wisdom until his death in 1008/9. He was succeeded by his son, Mansur, who managed to retain the throne until deposed in 1015/16.

The Battle of Andrassos or Adrassos was fought on 8 November 960 between the Byzantines, led by Leo Phokas the Younger, and the forces of the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo under the emir Sayf al-Dawla. It was fought in an unidentified mountain pass in the Taurus Mountains.

Abu 'l-Ma'ali Sharif, more commonly known by his honorific title, Sa'd al-Dawla, was the second ruler of the Hamdanid Emirate of Aleppo, encompassing most of northern Syria. The son of the emirate's founder, Sayf al-Dawla, he inherited the throne at a young age and in the midst of a major offensive by the Byzantine emperor Nikephoros II Phokas that within two years conquered the western portions of his realm and turned Aleppo into a tributary state. Facing a multitude of rebellions and desertions until 977, Sa'd was unable even to enter his own capital, which was in the hands of his father's chief minister, Qarquya. By maintaining close relations with the Buyids, he managed to re-establish his authority in parts of the Jazira, but his rule was soon challenged by the rebellion of his governor Bakjur, who was supported by the Fatimids of Egypt. In turn, Sa'd came to rely increasingly on Byzantine assistance, although he continued to fluctuate in his allegiance between Byzantium, the Buyids, and the Fatimids.

Uddat al-Dawla Abu Taghlib Fadl Allah al-Ghadanfar al-Hamdani, usually known simply by his kunya as Abu Taghlib, was the third Hamdanid ruler of the Emirate of Mosul, encompassing most of the Jazira.

Abu'l-Fada'il Sa'id al-Dawla was the third Hamdanid ruler of the Emirate of Aleppo. He succeeded his father Sa'd al-Dawla in 991, but throughout his reign real power rested in the hands of Sa'd al-Dawla's former chamberlain, Lu'lu', to whose daughter Sa'id was wed. His reign was dominated by the Fatimid Caliphate's repeated attempts to conquer Aleppo, which was prevented only by the intervention of the Byzantine Empire. Warfare lasted until 1000, when a peace treaty was concluded guaranteeing Aleppo's continued existence as a buffer state between the two powers. Finally, in January 1002 Sa'id al-Dawla died, possibly poisoned by Lu'lu', and Lu'lu' assumed control of Aleppo in his own name.

Mufarrij ibn Daghfal ibn al-Jarrah al-Tayyi, in some sources erroneously called Daghfal ibn Mufarrij, was an emir of the Jarrahid family and leader of the Tayy tribe. Mufarrij was engaged in repeated rebellions against the Fatimid Caliphate, which controlled southern Syria at the time. Although he was several times defeated and forced into exile, by the 990s Mufarrij managed to establish himself and his tribe as the de facto autonomous masters of much of Palestine around Ramlah with Fatimid acquiescence. In 1011, another rebellion against Fatimid authority was more successful, and a short-lived Jarrahid-led Bedouin state was established in Palestine centred at Ramlah. The Bedouin even proclaimed a rival Caliph to the Fatimid al-Hakim, in the person of the Alid Abu'l-Futuh al-Hasan ibn Ja'far. Bedouin independence survived until 1013, when the Fatimids launched their counterattack. Their will to resist weakened by Fatimid bribes, the Bedouin were quickly defeated. At the same time Mufarrij died, possibly poisoned, and his sons quickly came to terms with the Fatimids. Among them, Hassan ibn Mufarrij al-Jarrah managed to succeed to his father's position, and became a major player in the politics of the region over the next decades.

Abu'l-Qasim al-Husayn ibn Ali al-Maghribi, also called al-wazir al-Maghribi and by the surname al-Kamil Dhu'l-Wizaratayn, was the last member of the Banu'l-Maghribi, a family of statesmen who served in several Muslim courts of the Middle East in the 10th and early 11th centuries. Abu'l-Qasim himself was born in Hamdanid Aleppo before fleeing with his father to Fatimid Egypt, where he entered the bureaucracy. After his father's execution, he fled to Palestine, where he raised the local Bedouin leader Mufarrij ibn Daghfal to rebellion against the Fatimids (1011–13). As the rebellion began to falter, he fled to Iraq, where he entered the service of the Buyid emirs of Baghdad. Soon after he moved to the Jazira, where he entered the service of the Uqaylids of Mosul and finally the Marwanids of Mayyafariqin. He was also a poet and author of a number of treatises, including a "mirror for princes".

Alptakin was a Turkish military officer of the Buyids, who participated, and eventually came to lead, an unsuccessful rebellion against them in Iraq from 973 to 975. Fleeing west with 300 followers, he exploited the power vacuum in Syria to capture several cities, including Damascus. For the next three years, Alptakin withstood attempts by the Fatimid Caliphate to capture Damascus, until he was defeated and captured by Caliph al-Aziz Billah. Taken to Egypt and incorporated into the Fatimid army, he was poisoned by the vizier Ibn Killis shortly after this.

The Jarrahids were an Arab dynasty that intermittently ruled Palestine and controlled Transjordan and northern Arabia in the late 10th and early 11th centuries. They were described by historian Marius Canard (1888–1982) as a significant player in the Byzantine–Fatimid wars in Syria who "created for themselves, in their own best interests, a rule of duplicity, treason and pillage". They were the ruling family of the Tayy tribe, one of the three powerful tribes of Syria at the time; the other two were Kalb and Kilab.

Sharaf al-Maʿālī Abu Manṣūr Anūshtakīn al-Dizbarī was a Fatimid statesman and general who became the most powerful Fatimid governor of Syria. Under his Damascus-based administration, all of Syria was united under a single Fatimid authority. Near-contemporary historians, including Ibn al-Qalanisi of Damascus and Ibn al-Adim of Aleppo, noted Anushtakin's wealth, just rule and fair treatment of the population, with whom he was popular.

Abū'l-Futūh Barjawān al-Ustādh was a eunuch palace official who became the prime minister (wāsiṭa) and de facto regent of the Shia Fatimid Caliphate in October 997, and held the position until his assassination. Of obscure origin, Barjawan became the tutor of heir-apparent al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, who became caliph in 996 with the death of al-Aziz Billah. On al-Hakim's coronation, power was seized by the Kutama Berbers, who tried to monopolize government and clashed with their rivals, the Turkic slave-soldiers. Allied with disaffected Berber leaders, Barjawan was able to seize the reins of government for himself in 997. His tenure was marked by a successful balancing act between the Berbers and the Turks, as well as the rise of men of diverse backgrounds, promoted under his patronage. Militarily, Barjawan was successful in restoring order to the Fatimids' restive Levantine and Libyan provinces, and set the stage for an enduring truce with the Byzantine Empire. The concentration of power in his hands and his overbearing attitude alienated al-Hakim, however, who ordered him assassinated and thereafter assumed the governance of the caliphate himself.

Qarghuyah or Qarquya was an important Arab administrator in the Hamdanid Dynasty under Sayf al-Dawla, who would go on to control Aleppo himself and even sign the Treaty of Safar with the Byzantine Empire as the ruling emir of Aleppo.

Abu Abdallah al-Husayn ibn Nasir al-Dawla was a Hamdanid prince, who along with his brother Ibrahim was the last Hamdanid ruler of Mosul in 989–990. After his defeat at the hand of the Marwanid Kurds and the takeover of Mosul by the Uqaylids, he entered the service of the Fatimid Caliphate.