A Bantustan was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa, as part of its policy of apartheid. By extension, outside South Africa the term refers to regions that lack any real legitimacy, consisting often of several unconnected enclaves, or which have emerged from national or international gerrymandering.

Ciskei was a Bantustan for the Xhosa people-located in the southeast of South Africa. It covered an area of 7,700 square kilometres (3,000 sq mi), almost entirely surrounded by what was then the Cape Province, and possessed a small coastline along the shore of the Indian Ocean.

King Kaiser Daliwonga Mathanzima, misspelled Matanzima, was the long-term leader of Transkei. In 1950, when South Africa was offered to establish the Bantu Authorities Act, Matanzima convinced the Bunga to accept the Act. The Bunga were the council of Transkei chiefs, who at first rejected the Act until 1955 when Matanzima persuaded them.

The Bantu Education Act 1953 was a South African segregation law that legislated for several aspects of the apartheid system. Its major provision enforced racially-separated educational facilities. Even universities were made "tribal", and all but three missionary schools chose to close down when the government would no longer help to support their schools. Very few authorities continued using their own finances to support education for native Africans. In 1959, that type of education was extended to "non-white" universities and colleges with the Extension of University Education Act, and the University College of Fort Hare was taken over by the government and degraded to being part of the Bantu education system. It is often argued that the policy of Bantu (African) education was aimed to direct black or non-white youth to the unskilled labour market although Hendrik Verwoerd, the Minister of Native Affairs, claimed that the aim was to solve South Africa's "ethnic problems" by creating complementary economic and political units for different ethnic groups.

Kavangoland was a bantustan in South West Africa, intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Kavango people. After the legal framework was established in 1968 as the Development of Self-Government for Native Nations in South-West Africa Act, 1968, Kavangoland was set up in 1970 and self-government was granted in 1973. The Kavango Legislative Council had its administrative headquarters in Rundu; its first session opened in October 1970 in the presence of the South African Minister for Bantu Administration and Development.

East Caprivi or Itenge was a bantustan in South West Africa, intended by the apartheid government to be a self-governing homeland for the Masubiya people. It was set up in 1972, in the very corner of the Namibian panhandle called the Caprivi Strip. It was granted a self-governing status in 1976. The homeland was renamed Zambezi Region soon after. Unlike the other homelands in South West Africa, East Caprivi was administered through the Department of Bantu Administration and Development in Pretoria.

The Bantu Homelands Citizenship Act, 1970 was a Self Determination or denaturalization law passed during the apartheid era of South Africa that allocated various tribes/nations of black South Africans as citizens of their traditional black tribal "homelands," or Bantustans.

South African Bantu-speaking peoples represent the overwhelming majority ethno-racial group of South Africa. Occasionally grouped as Bantu, the term itself is derived from the English word “people", common to many of the Bantu languages. The Oxford Dictionary of South African English describes “Bantu”, when used in a contemporary usage and or racial context as "obsolescent and offensive", because of its strong association with the “white minority rule” with their apartheid system, however, Bantu is used without pejorative connotations in other parts of Africa and is still used in South Africa as the group term for the language family.

The World, originally named The Bantu World, was the black daily newspaper of Johannesburg, South Africa. It is famous for publishing Sam Nzima's iconic photograph of Hector Pieterson, taken during the Soweto uprising of 16 June 1976.

The Promotion of Bantu Self-Government Act, 1959 was an important piece of South African apartheid legislation that allowed for the transformation of traditional tribal lands into "fully fledged independent states Bantustans", which would supposedly provide for the right to self-determination of the country's black population. It also resulted in the abolition of parliamentary representation for black South Africans, an act furthered in 1970 with the passage of the Black Homeland Citizenship Act.

The system of racial segregation and oppression in South Africa known as apartheid was implemented and enforced by many acts and other laws. This legislation served to institutionalize racial discrimination and the dominance by white people over people of other races. While the bulk of this legislation was enacted after the election of the National Party government in 1948, it was preceded by discriminatory legislation enacted under earlier British and Afrikaner governments. Apartheid is distinguished from segregation in other countries by the systematic way in which it was formalized in law.

King Botha Sigcau was a King in Eastern Pondoland, Transkei, South Africa (1939–1976) and later the figurehead President of Transkei from 1976 to 1978. A graduate of the University of Fort Hare, Sigcau was an early supporter of the Bantu Authorities in Transkei and was rewarded by the South African government when he was appointed chairman of the Transkei Territorial Authority, the parliament before independence.

Black suffrage refers to black people's right to vote and has long been an issue in countries established under conditions of black minorities.

Jongilizwe College was a school in Tsolo, Transkei, South Africa which served the sons of Chiefs and Headmen from the Transkei bantustan.

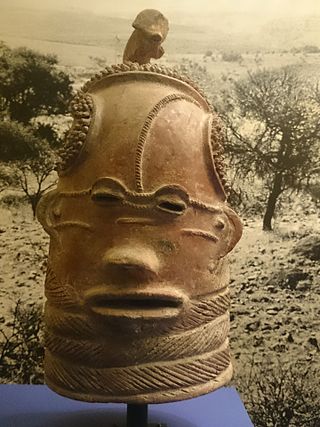

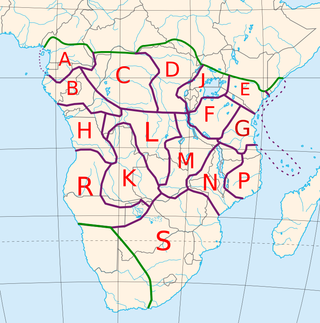

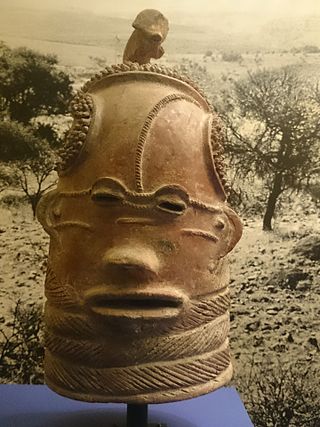

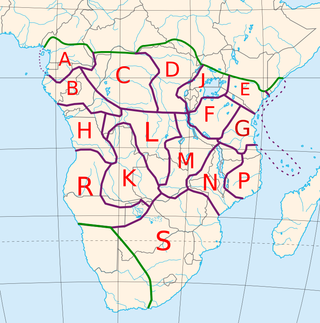

The Bantu peoples, or Bantu, are an ethnolinguistic grouping of approximately 400 distinct ethnic groups who speak Bantu languages, consisting of some 600 languages with varied mutual intelligibility. The languages are native to 24 countries spread over a vast area from Central Africa to Southeast Africa and into Southern Africa. There are several hundred Bantu languages. Depending on the definition of "language" or "dialect", it is estimated that there are between 440 and 680 distinct languages. The total number of speakers is in the hundreds of millions, ranging at roughly 350 million in the mid-2010s. About 60 million speakers (2015), divided into some 200 ethnic or tribal groups, are found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo alone.

Hlubi is a minor Bantu language of South Africa, traditionally considered a dialect of Swazi. It is spoken in South Africa, near where the Xhosa, Sotho, and Phuthi languages meet at the Orange River and the southern point of Lesotho. The scattered Hlubi people speak several languages, including Swazi, and the Hlubi dialect of Xhosa in the former Bantustan of Ciskei.

The Tomlinson Report was a 1954 report released by the Commission for the Socioeconomic Development of the Bantu Areas, known as the Tomlinson Commission, that was commissioned by the South African government to study the economic viability of the native reserves. These reserves were intended to serve as the homelands for the black population. The report is named for Frederick R. Tomlinson, professor of agricultural economics at the University of Pretoria. Tomlinson chaired the ten-person commission, which was established in 1950. The Tomlinson Report found that the reserves were incapable of containing South Africa's black population without significant state investment. However, Hendrik Verwoerd, Minister of Native Affairs, rejected several recommendations in the report. While both Verwoerd and the Tomlinson Commission believed in "separate development" for the reserves, Verwoerd did not want to end economic interdependence between the reserves and industries in white-controlled areas. The government would go on to pass legislation to restrict the movement of blacks who lived in the reserves to white-controlled areas.

The 1987 Transkei coup d'état was a bloodless military coup in Transkei, an unrecognised state and a nominally independent South African homeland for the Xhosa people, which took place on 30 December 1987. The coup was led by the then 32-year-old Major General Bantu Holomisa, the Chief of the Transkei Defence Force, against the government of Prime Minister Stella Sigcau (TNIP). Holomisa suspended the civilian constitution and refused South Africa's repeated demands for a return to civilian rule on the grounds that a civilian government would be a puppet controlled by Pretoria.