Albert John Luthuli was a South African anti-apartheid activist, traditional leader, and politician who served as the President-General of the African National Congress from 1952 until his death in 1967.

General elections were held in South Africa between 26 and 29 April 1994. The elections were the first in which citizens of all races were allowed to take part, and were therefore also the first held with universal suffrage. The election was conducted under the direction of the Independent Electoral Commission (IEC), and marked the culmination of the four-year process that ended apartheid.

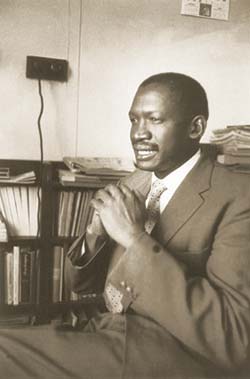

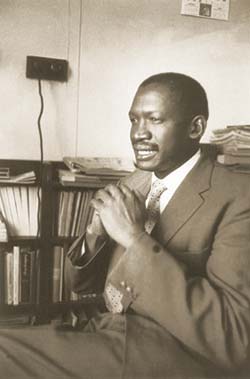

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe OMSG was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary and founding member of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), serving as the first president of the organization.

The Suppression of Communism Act, 1950, renamed the Internal Security Act in 1976, was legislation of the national government in apartheid South Africa which formally banned the Communist Party of South Africa and proscribed any party or group subscribing to communism, according to a uniquely broad definition of the term. It was also used as the basis to place individuals under banning orders, and its practical effect was to isolate and silence voices of dissent.

The following lists events that happened during 1960 in South Africa.

In South Africa under apartheid, and South West Africa, pass laws served as an internal passport system designed to racially segregate the population, restrict movement of individuals, and allocate low-wage migrant labor. Also known as the natives' law, these laws severely restricted the movements of Black South African and other racial groups by confining them to designated areas. Initially applied to African men, attempts to enforce pass laws on women in the 1910s and 1950s sparked significant protests. Pass laws remained a key aspect of the country's apartheid system until their effective termination in 1986. The pass document used to enforce these laws was derogatorily referred to as the dompas.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an authoritarian political culture based on baasskap, which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation's minority white population. Under this minoritarian system, white citizens held the highest status, followed by Indians, Coloureds and black Africans, in that order. The economic legacy and social effects of apartheid continue to the present day, particularly inequality.

Zephania Lekoame Mothopeng was a South African political activist and member of the Pan-Africanist Congress (PAC).

Law enforcement in South Africa is primarily the responsibility of the South African Police Service (SAPS), South Africa's national police force. SAPS is responsible for investigating crime and security throughout the country. The "national police force is crucial for the safety of South Africa's citizens" and was established in accordance with the provisions of Section 205 of the Constitution of South Africa.

Internal resistance to apartheid in South Africa originated from several independent sectors of South African society and took forms ranging from social movements and passive resistance to guerrilla warfare. Mass action against the ruling National Party (NP) government, coupled with South Africa's growing international isolation and economic sanctions, were instrumental in leading to negotiations to end apartheid, which began formally in 1990 and ended with South Africa's first multiracial elections under a universal franchise in 1994.

The African National Congress (ANC) has been the governing party of the Republic of South Africa since 1994. The ANC was founded on 8 January 1912 in Bloemfontein and is the oldest liberation movement in Africa.

This article covers the history of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, once a South African liberation movement and now a minor political party.

In 1953, the Public Safety Act was enacted by the apartheid South African government. This Act empowered the government to declare stringent states of emergency and increased penalties for protesting against or supporting the repeal of a law.

The Riotous Assemblies Act, Act No 17 of 1956 in South Africa prohibited gatherings in open-air public places if the Minister of Justice considered they could endanger the public peace. Banishment was also included as a form of punishment.

On 2 February 1990, the State President of South Africa F. W. de Klerk delivered a speech at the opening of the 1990 session of the Parliament of South Africa in Cape Town in which he announced sweeping reforms that marked the beginning of the negotiated transition from apartheid to constitutional democracy. The reforms promised in the speech included the unbanning of the African National Congress (ANC) and other anti-apartheid organisations, the release of political prisoners including Nelson Mandela, the end of the state of emergency, and a moratorium on the death penalty.

The Internal Security Act, 1982 was an act of the Parliament of South Africa that consolidated and replaced various earlier pieces of security legislation, including the Suppression of Communism Act, 1950, parts of the Riotous Assemblies Act, 1956, the Unlawful Organizations Act, 1960 and the Terrorism Act, 1967. It gave the apartheid government broad powers to ban or restrict organisations, publications, people and public gatherings, and to detain people without trial. The Act was passed as a consequence of the recommendations of the Rabie Commission, which had enquired into the state of security legislation.

Clarence Mlami Makwetu was a South African anti-apartheid activist, politician, and leader of the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC) during the historic 1994 elections.

Dorothy Nomzansi Nyembe OMSS was a South African activist and politician.

Robben Island Prison is an inactive prison on Robben Island in Table Bay, 6.9 kilometers (4.3 mi) west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, Cape Town, South Africa. Nobel Laureate and former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela was imprisoned there for 18 of the 27 years he served behind bars before the fall of apartheid. Since then, three former inmates of the prison have gone on to become President of South Africa.

The Security Branch of the South African Police, established in 1947 as the Special Branch, was the security police apparatus of the apartheid state in South Africa. From the 1960s to the 1980s, it was one of the three main state entities responsible for intelligence gathering, the others being the Bureau for State Security and the Military Intelligence division of the South African Defence Force. In 1987, at its peak, the Security Branch accounted for only thirteen percent of police personnel, but it wielded great influence as the "elite" service of the police.