The University of Fort Hare is a public university in Alice, Eastern Cape, South Africa.

A Bantustan was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa, as a part of its policy of apartheid.

Coloureds refers to members of multiracial ethnic communities in South Africa who may have ancestry from African, European, and Asian people. The intermixing of different races began in the Cape province of South Africa, with Dutch settlers, African and Malaysian slaves intermixing with the indigenous Khoi tribes of that region. Later various other European nationals also contributed to the growing mixed race people, who would later be officially classified as coloured by the apartheid government in the 1950s.

In South Africa, Asian usually refers to people of South Asian ancestry, more commonly called Indians. They are largely descended from people who migrated to South Africa in the late 19th and early 20th century from British ruled South Asia.

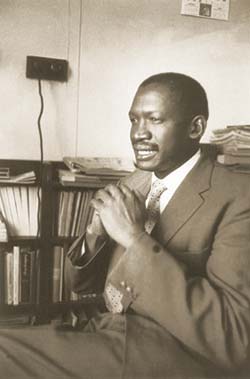

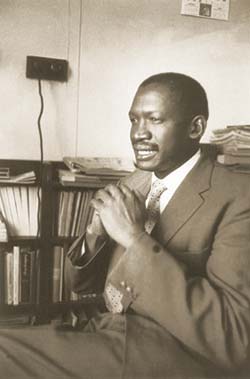

Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe OMSG was a South African anti-apartheid revolutionary and founding member of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), serving as the first president of the organization.

Zachariah Keodirelang Matthews OLG was a prominent black academic in South Africa, lecturing at South African Native College, where many future leaders of the African continent were among his students.

The British diaspora in Africa is a population group broadly defined as English-speaking people of mainly British descent who live in or were born in Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority live in South Africa and other Southern African countries in which English is a primary language, including Zimbabwe, Namibia, Kenya, Botswana, Zambia. Their first language is usually English.

The Bantu Education Act 1953 was a South African segregation law that legislated for several aspects of the apartheid system. Its major provision enforced racially-separated educational facilities; Even universities were made "tribal", and all but three missionary schools chose to close down when the government would no longer help to support their schools. Very few authorities continued using their own finances to support education for native Africans. In 1959, that type of education was extended to "non-white" universities and colleges with the, and the University College of Fort Hare was taken over by the government and degraded to being part of the Bantu education system. It is often argued that the policy of Bantu (African) education was aimed to direct black or non-white youth to the unskilled labour market although Hendrik Verwoerd, the Minister of Native Affairs, claimed that the aim was to solve South Africa's "ethnic problems" by creating complementary economic and political units for different ethnic groups.

The University of the Western Cape is a public research university in Bellville, near Cape Town, South Africa. The university was established in 1959 by the South African government as a university for Coloured people only. Other universities in Cape Town are the University of Cape Town, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, and Stellenbosch University. The establishing of UWC was a direct effect of the Extension of University Education Act, 1959. This law accomplished the segregation of higher education in South Africa. Coloured students were only allowed at a few non-white universities. In this period, other "ethnical" universities, such as the University of Zululand and the University of the North, were founded as well. Since well before the end of apartheid in South Africa in 1994, it has been an integrated and multiracial institution.

Apartheid was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa from 1948 to the early 1990s. Apartheid was characterised by an authoritarian political culture based on baasskap, which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation's minority white population. In this minoritarian system, there was social stratification, where white citizens had the highest status, followed by Indians and Coloureds, then Black Africans. The economic legacy and social effects of apartheid continue to the present day, particularly inequality.

A technikon was a post-secondary institute of technology (polytech) in South Africa. It focused on career-oriented vocational training. There were 15 technikons in the 1990s, but they were merged or restructured as universities in the early 2000s.

The Black Sash is a South African human rights organisation. It was founded in Johannesburg in 1955 as a non-violent resistance organisation for liberal white women.

The South African Students' Organisation (SASO) was a body of black South African university students who resisted apartheid through non-violent political action. The organisation was formed in 1969 under the leadership of Steve Biko and Barney Pityana and made vital contributions to the ideology and political leadership of the Black Consciousness Movement. It was banned by the South African government in October 1977, as part of the repressive state response to the Soweto uprising.

The system of racial segregation and oppression in South Africa known as apartheid was implemented and enforced by many acts and other laws. This legislation served to institutionalize racial discrimination and the dominance by white people over people of other races. While the bulk of this legislation was enacted after the election of the National Party government in 1948, it was preceded by discriminatory legislation enacted under earlier British and Afrikaner governments. Apartheid is distinguished from segregation in other countries by the systematic way in which it was formalized in law.

The 1994 Bophuthatswana crisis was a major political crisis which began after Lucas Mangope, the president of Bophuthatswana, a nominally independent South African bantustan created under apartheid, attempted to crush widespread labour unrest and popular demonstrations demanding the incorporation of the territory into South Africa pending non-racial elections later that year. Violent protests immediately broke out following President Mangope's announcement on 7 March that Bophuthatswana would boycott the South African general elections. This was escalated by the arrival of right-wing Afrikaner militias seeking to preserve the Mangope government. The predominantly black Bophuthatswana Defence Force and police refused to cooperate with the white extremists and mutinied, then forced the Afrikaner militias to leave Bophuthatswana. The South African military entered Bophuthatswana and restored order on 12 March.

Internal resistance to apartheid in South Africa originated from several independent sectors of South African society and took forms ranging from social movements and passive resistance to guerrilla warfare. Mass action against the ruling National Party (NP) government, coupled with South Africa's growing international isolation and economic sanctions, were instrumental in leading to negotiations to end apartheid, which began formally in 1990 and ended with South Africa's first multiracial elections under a universal franchise in 1994.

This article focuses on the history of 19th century Xhosa language newspapers in South Africa.

Racial groups in South Africa have a variety of origins. The racial categories introduced by Apartheid remain ingrained in South African society with South Africans and the governing party of South Africa continuing to classify themselves, and each other, as belonging to one of the four defined race groups. Statistics South Africa asks people to describe themselves in the census in terms of five racial population groups. The 2022 estimates were 81.4% Black or Indigenous South African, 7.3% White South African, 8.2% Coloured South African, and 2.7% Indian South African.

The Cape Qualified Franchise was the system of non-racial franchise that was adhered to in the Cape Colony, and in the Cape Province in the early years of the Union of South Africa. Qualifications for the right to vote at parliamentary elections were applied equally to all men, regardless of race.

Selby Mvusi (1929–1967) was a South African artist. He was born in Richmond, KwaZulu-Natal, on 18 June 1929. In 1961 he took a post at Clarke College, Atlanta, Georgia. He died in a car crash near Nairobi, Kenya, on 10 December 1967. In 2015 Elza Miles wrote a biography of Mvusi, called Selby Mvusi: To Fly with the North Bird South.