Related Research Articles

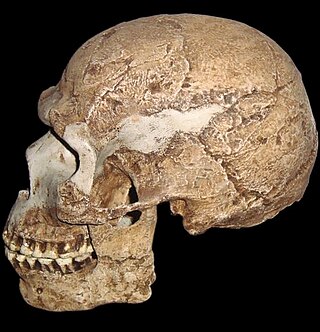

Early modern human (EMH), or anatomically modern human (AMH), are terms used to distinguish Homo sapiens that are anatomically consistent with the range of phenotypes seen in contemporary humans, from extinct archaic human species. This distinction is useful especially for times and regions where anatomically modern and archaic humans co-existed, for example, in Paleolithic Europe. Among the oldest known remains of Homo sapiens are those found at the Omo-Kibish I archaeological site in south-western Ethiopia, dating to about 233,000 to 196,000 years ago, the Florisbad site in South Africa, dating to about 259,000 years ago, and the Jebel Irhoud site in Morocco, dated about 315,000 years ago.

Neanderthals became extinct around 40,000 years ago. Hypotheses on the causes of the extinction include violence, transmission of diseases from modern humans which Neanderthals had no immunity to, competitive replacement, extinction by interbreeding with early modern human populations, natural catastrophes, climate change and inbreeding depression. It is likely that multiple factors caused the demise of an already low population.

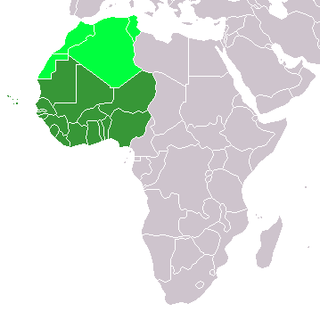

The history of West Africa has been divided into its prehistory, the Iron Age in Africa, the period of major polities flourishing, the colonial period, and finally the post-independence era, in which the current nations were formed. West Africa is west of an imagined north–south axis lying close to 10° east longitude, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and Sahara Desert. Colonial boundaries are reflected in the modern boundaries between contemporary West African states, cutting across ethnic and cultural lines, often dividing single ethnic groups between two or more states.

Human genetic variation is the genetic differences in and among populations. There may be multiple variants of any given gene in the human population (alleles), a situation called polymorphism.

Peștera cu Oase is a system of 12 karstic galleries and chambers located near the city Anina, in the Caraș-Severin county, southwestern Romania, where some of the oldest European early modern human (EEMH) remains, between 42,000 and 37,000 years old, have been found.

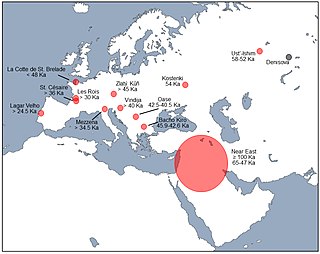

Early human migrations are the earliest migrations and expansions of archaic and modern humans across continents. They are believed to have begun approximately 2 million years ago with the early expansions out of Africa by Homo erectus. This initial migration was followed by other archaic humans including H. heidelbergensis, which lived around 500,000 years ago and was the likely ancestor of Denisovans and Neanderthals as well as modern humans. Early hominids had likely crossed land bridges that have now sunk.

Mechta-Afalou, also known as Mechtoid or Paleo-Berber, are a population that inhabited parts of North Africa during the late Paleolithic and Mesolithic. They are associated with the Iberomaurusian archaeological culture.

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is locally known as the Eastern Oranian. The Iberomaurusian seems to have appeared around the time of the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), somewhere between c. 25,000 and 23,000 cal BP. It would have lasted until the early Holocene c. 11,000 cal BP.

In paleoanthropology, the recent African origin of modern humans or the "Out of Africa" theory (OOA) is the most widely accepted model of the geographic origin and early migration of anatomically modern humans. It follows the early expansions of hominins out of Africa, accomplished by Homo erectus and then Homo neanderthalensis.

The multiregional hypothesis, multiregional evolution (MRE), or polycentric hypothesis, is a scientific model that provides an alternative explanation to the more widely accepted "Out of Africa" model of monogenesis for the pattern of human evolution.

The Denisovans or Denisova hominins(di-NEE-sə-və) are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic human that ranged across Asia during the Lower and Middle Paleolithic. Denisovans are known from few physical remains; consequently, most of what is known about them comes from DNA evidence. No formal species name has been established pending more complete fossil material.

Neanderthals, also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. The type specimen, Neanderthal 1, was found in 1856 in the Neander Valley in present-day Germany.

There is evidence for interbreeding between archaic and modern humans during the Middle Paleolithic and early Upper Paleolithic. The interbreeding happened in several independent events that included Neanderthals and Denisovans, as well as several unidentified hominins.

Taforalt, or Grotte des Pigeons, is a cave in the province of Berkane, Aït Iznasen region, Morocco, possibly the oldest cemetery in North Africa. It contained at least 34 Iberomaurusian adolescent and adult human skeletons, as well as younger ones, from the Upper Palaeolithic between 15,100 and 14,000 calendar years ago. There is archaeological evidence for Iberomaurusian occupation at the site between 23,200 and 12,600 calendar years ago, as well as evidence for Aterian occupation as old as 85,000 years.

A ghost population is a population that has been inferred through using statistical techniques.

Genetic studies on Neanderthal ancient DNA became possible in the late 1990s. The Neanderthal genome project, established in 2006, presented the first fully sequenced Neanderthal genome in 2013.

Basal Eurasian is a proposed lineage of anatomically modern humans with reduced, or zero, archaic hominin (Neanderthal) admixture compared to other ancient non-Africans. Basal Eurasians represent a sister lineage to other Eurasians and may have originated from the Southern Middle East, specifically the Arabian peninsula, or North Africa, and are said to have contributed ancestry to various West Eurasian, South Asian, and Central Asian groups. This hypothetical population was proposed to explain the lower archaic admixture among modern West Eurasians compared to with East Eurasians, although alternatives without the need of such Basal lineage exist as well.

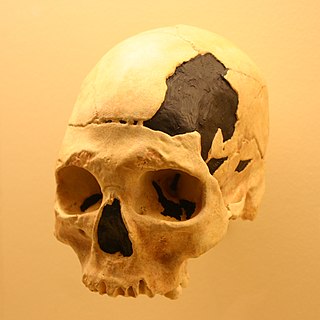

Iwo Eleru is an archaeological site and rock shelter that features Later Stone Age artifacts from during the Late Pleistocene-Holocene transition, which is uniquely located in the forest–savanna region of Isarun, Nigeria. The site was initially reported with this name, by Chief Officer J. Akeredolu, in 1961. The correct name for the site was later recognized to be Ihò Eléérú, or Iho Eleru, meaning "Cave of Ashes." The Iho Eleru skull is a notable archaeological discovery from the excavation site of Iho Eleru in Ondo State, Yorubaland, Nigeria. The Iho Eleru fossil, which dates to approximately 13,000 years old, may be evidence of modern humans possessing possible archaic human admixture or of a late-persisting early modern human.

The genetic history of Africa is composed of the overall genetic history of African populations in Africa, including the regional genetic histories of North Africa, West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa, and Southern Africa, as well as the recent origin of modern humans in Africa. The Sahara served as a trans-regional passageway and place of dwelling for people in Africa during various humid phases and periods throughout the history of Africa.

The population history of West Africa is composed of West African populations that were considerably mobile and interacted with one another throughout the history of West Africa. Acheulean tool-using archaic humans may have dwelled throughout West Africa since at least between 780,000 BP and 126,000 BP. During the Pleistocene, Middle Stone Age peoples, who dwelled throughout West Africa between MIS 4 and MIS 2, were gradually replaced by incoming Late Stone Age peoples, who migrated into West Africa as an increase in humid conditions resulted in the subsequent expansion of the West African forest. West African hunter-gatherers occupied western Central Africa earlier than 32,000 BP, dwelled throughout coastal West Africa by 12,000 BP, and migrated northward between 12,000 BP and 8000 BP as far as Mali, Burkina Faso, and Mauritania.

References

- 1 2 3 Capelli, Cristian; Montinaro, Francesco (October 24, 2018). "Genetics and Southern African History". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Research Archive. p. 7. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.446. ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4. S2CID 134983982.

- 1 2 3 Montinaro, Francesco; Capelli, Cristian (2018). "The evolutionary history of Southern Africa". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 53: 160. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2018.11.003. PMID 30522870. S2CID 54483869.

- 1 2 Vidal, Gerard Serra (2018). "Insights into the human demographic history of Africa through whole-genome sequence analysis" (PDF). Universitat Pompeu Fabra Barcelona. p. 162. S2CID 108974583.

- 1 2 3 Durvasula, Arun; Sankararaman, Sriram (2020). "Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations". Science Advances. 6 (7): eaax5097. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5097D. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax5097. ISSN 2375-2548. OCLC 8538353312. PMC 7015685 . PMID 32095519. S2CID 211472946.

- ↑ Sirak, Kendra A.; Sawchuk, Elizabeth A.; Prendergast, Mary E. (18 May 2022). "Ancient Human DNA and African Population History" (PDF). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History. Oxford University Press. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Durvasula A, Sankararaman S (February 2020). "Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations". Science Advances. 6 (7): eaax5097. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5097D. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aax5097 . PMC 7015685 . PMID 32095519. "Non-African populations (Han Chinese in Beijing and Utah residents with northern and western European ancestry) also show analogous patterns in the CSFS, suggesting that a component of archaic ancestry was shared before the split of African and non-African populations...One interpretation of the recent time of introgression that we document is that archaic forms persisted in Africa until fairly recently. Alternately, the archaic population could have introgressed earlier into a modern human population, which then subsequently interbred with the ancestors of the populations that we have analyzed here. The models that we have explored here are not mutually exclusive, and it is plausible that the history of African populations includes genetic contributions from multiple divergent populations, as evidenced by the large effective population size associated with the introgressing archaic population...Given the uncertainty in our estimates of the time of introgression, we wondered whether jointly analyzing the CSFS from both the CEU (Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry) and YRI genomes could provide additional resolution. Under model C, we simulated introgression before and after the split between African and non-African populations and observed qualitative differences between the two models in the high-frequency–derived allele bins of the CSFS in African and non-African populations (fig. S40). Using ABC to jointly fit the high-frequency–derived allele bins of the CSFS in CEU and YRI (defined as greater than 50% frequency), we find that the lower limit on the 95% credible interval of the introgression time is older than the simulated split between CEU and YRI (2800 versus 2155 generations B.P.), indicating that at least part of the archaic lineages seen in the YRI are also shared with the CEU..."

- ↑ Archived 7 December 2020 at the Wayback Machine Supplementary Materials for Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations", section "S8.2" "We simulated data using the same priors in Section S5.2, but computed the spectrum for both YRI [West African Yoruba] and CEU [a population of European origin] . We found that the best fitting parameters were an archaic split time of 27,000 generations ago (95% HPD: 26,000-28,000), admixture fraction of 0.09 (95% HPD: 0.04-0.17), admixture time of 3,000 generations ago (95% HPD: 2,800-3,400), and an effective population size of 19,700 individuals (95% HPD: 19,300-20,200). We find that the lower bound of the admixture time is further back than the simulated split between CEU and YRI (2155 generations ago), providing some evidence in favor of a pre-Out-of-Africa event. This model suggests that many populations outside of Africa should also contain haplotypes from this introgression event, though detection is difficult because many methods use unadmixed outgroups to detect introgressed haplotypes [Browning et al., 2018, Skov et al., 2018, Durvasula and Sankararaman, 2019] (5, 53, 22). It is also possible that some of these haplotypes were lost during the Out-of-Africa bottleneck."

- ↑ Durvasula A, Sankararaman S (February 2020). "Recovering signals of ghost archaic introgression in African populations". Science Advances. 6 (7): eaax5097. Bibcode:2020SciA....6.5097D. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aax5097. PMC 7015685 . PMID 32095519.

- ↑ Chen L, Wolf AB, Fu W, Li L, Akey JM (February 2020). "Identifying and Interpreting Apparent Neanderthal Ancestry in African Individuals". Cell. 180 (4): 677–687.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.01.012 . PMID 32004458. S2CID 210955842.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Skoglund, Pontus; et al. (2017). "Reconstructing Prehistoric African Population Structure". Cell. 171 (1): 59–71.e21. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.049. ISSN 0092-8674. OCLC 7144495602. PMC 5679310 . PMID 28938123. S2CID 1257429.

- 1 2 Lipson, Mark; et al. (2020). "Ancient West African foragers in the context of African population history". Nature. 577 (7792): 668–669. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..665L. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-1929-1. ISSN 0028-0836. OCLC 8516105991. PMC 8386425 . PMID 31969706. S2CID 210862788.

- 1 2 Jeong, Choongwon (2020). "Current Trends in Ancient DNA Study: Beyond Human Migration in and Around Europe". The Handbook of Mummy Studies: New Frontiers in Scientific and Cultural Perspectives. Springer Nature. p. 6. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1614-6_10-1. ISBN 978-981-15-1614-6. OCLC 1182512815. S2CID 226555687.

- ↑ Wonkam, Ambroise; et al. (2022). "Exome sequencing of families from Ghana reveals known and candidate hearing impairment genes". Communications Biology. 5 (1): 369. doi:10.1038/s42003-022-03326-8. OCLC 9478623435. PMC 9019055 . PMID 35440622. S2CID 248264573.