The Punic language, also called Phoenicio-Punic or Carthaginian, is an extinct variety of the Phoenician language, a Canaanite language of the Northwest Semitic branch of the Semitic languages. An offshoot of the Phoenician language of coastal West Asia, it was principally spoken on the Mediterranean coast of Northwest Africa, the Iberian peninsula and several Mediterranean islands, such as Malta, Sicily, and Sardinia by the Punic people, or western Phoenicians, throughout classical antiquity, from the 8th century BC to the 6th century AD.

The sarcophagus ofEshmunazar II is a 6th-century BC sarcophagus unearthed in 1855 in the grounds of an ancient necropolis southeast of the city of Sidon, in modern-day Lebanon, that contained the body of Eshmunazar II, Phoenician King of Sidon. One of only three Ancient Egyptian sarcophagi found outside Egypt, with the other two belonging to Eshmunazar's father King Tabnit and to a woman, possibly Eshmunazar's mother Queen Amoashtart, it was likely carved in Egypt from local amphibolite, and captured as booty by the Sidonians during their participation in Cambyses II's conquest of Egypt in 525 BC. The sarcophagus has two sets of Phoenician inscriptions, one on its lid and a partial copy of it on the sarcophagus trough, around the curvature of the head. The lid inscription was of great significance upon its discovery as it was the first Phoenician language inscription to be discovered in Phoenicia proper and the most detailed Phoenician text ever found anywhere up to that point, and is today the second longest extant Phoenician inscription, after the Karatepe bilingual.

The Cippus Perusinus is a stone tablet (cippus) discovered on the hill of San Marco, in Perugia, Italy, in 1822. The tablet bears 46 lines of incised Etruscan text, about 130 words. The cippus, which seems to have been a border stone, appears to display a text dedicating a legal contract between the Etruscan families of Velthina and Afuna, regarding the sharing or use, including water rights, of a property upon which there was a tomb belonging to the noble Velthinas.

The Nora Stone or Nora Inscription is an ancient Phoenician inscribed stone found at Nora on the south coast of Sardinia in 1773. Though it was not discovered in its primary context, it has been dated by palaeographic methods to the late 9th century to early 8th century BCE and is still considered the oldest Phoenician inscription found anywhere outside of the Levant.

Eshmunazar II was the Phoenician king of Sidon. He was the grandson of Eshmunazar I, and a vassal king of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar II succeeded his father Tabnit I who ruled for a short time and died before the birth of his son. Tabnit I was succeeded by his sister-wife Amoashtart who ruled alone until Eshmunazar II's birth, and then acted as his regent until the time he would have reached majority. Eshmunazar II died prematurely at the age of 14. He was succeeded by his cousin Bodashtart.

Bodashtart was a Phoenician ruler, who reigned as King of Sidon, the grandson of King Eshmunazar I, and a vassal of the Achaemenid Empire. He succeeded his cousin Eshmunazar II to the throne of Sidon, and scholars believe that he was succeeded by his son and proclaimed heir Yatonmilk.

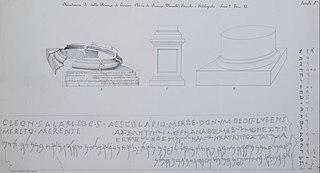

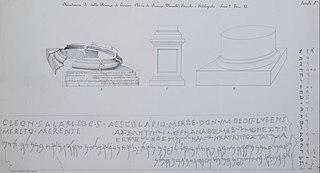

The Cippi of Melqart are a pair of Phoenician marble cippi that were unearthed in Malta under undocumented circumstances and dated to the 2nd century BC. These are votive offerings to the god Melqart, and are inscribed in two languages, Ancient Greek and Phoenician, and in the two corresponding scripts, the Greek and the Phoenician alphabet. They were discovered in the late 17th century, and the identification of their inscription in a letter dated 1694 made them the first Phoenician writing to be identified and published in modern times. Because they present essentially the same text, the cippi provided the key to the modern understanding of the Phoenician language. In 1758, the French scholar Jean-Jacques Barthélémy relied on their inscription, which used 17 of the 22 letters of the Phoenician alphabet, to decipher the unknown language.

Antonio Taramelli was an Italian archaeologist.

The Nuragic sanctuary of Santa Vittoria is an archaeological site located in the municipality of Serri, Sardinia – Italy. The name refers to the Romanesque style church built over a place of Roman worship which rises at the westernmost tip of the site. The Santa Vittoria site was frequented starting from the first phase of the Nuragic civilization corresponding to Middle Bronze Age. Subsequently, from the late Bronze Age to the early Iron Age, the place became one of the most important expressions of the Nuragic civilization and today it constitutes the most important Nuragic complex so far excavated.

The National Archaeological Museum of Cagliari is a museum in Cagliari, Sardinia (Italy).

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts. The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.

The Pauli Gerrei trilingual inscription is a trilingual Greek-Latin-Phoenician inscription on the base of a bronze column found in San Nicolò Gerrei in Sardinia in 1861. The stele was discovered by a notary named Michele Cappai, on the right side of the Strada statale 387 del Gerrei that descends towards Ballao.

Eshmunazar I was a priest of Astarte and the Phoenician King of Sidon. He was the founder of his namesake dynasty, and a vassal king of the Achaemenid Empire. Eshmunazar participated in the Neo-Babylonian campaigns against Egypt under the command of either Nebuchadnezzar II or Nabonidus. The Sidonian king is mentioned in the funerary inscriptions engraved on the royal sarcophagi of his son Tabnit I and his grandson Eshmunazar II. The monarch's name is also attested in the dedicatory temple inscriptions of his other grandson, King Bodashtart.

The Carthage Administration Inscription is an inscription in the Punic language, using the Phoenician alphabet, discovered on the archaeological site of Carthage in the 1960s and preserved in the National Museum of Carthage. It is known as KAI 303.

The Tripolitania Punic inscriptions are a number of Punic language inscriptions found in the region of Tripolitania – specifically its three classical cities of Leptis Magna, Sabratha and Oea (Tripoli), with the vast majority being found in Leptis Magna. The inscriptions have been found in various periods over the last two centuries, and were catalogued by Giorgio Levi Della Vida. A subset of the inscriptions feature in all the major corpuses of Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, notably as KAI 119-132.

The Olbia pedestal is a Punic language inscription from the [third] century BCE, found 1911 at Olbia in Sardinia.

The Tharros Punic inscriptions are a group of Punic inscriptions found at the archeological site of Tharros in Sardinia.

The Jatta National Archaeological Museum in Ruvo di Puglia, a historic and artistic city in southern Italy, is housed in rooms of Palazzo Jatta and represents the only example in Italy of a nineteenth-century private collection that has remained unaltered from its original museographic concept. The finds preserved in the museum were collected by the archaeologist Giovanni Jatta in the early nineteenth century and his collection was subsequently enriched by his nephew of the same name and was sold to the Italian state in the twentieth century.

The Persephone Punic stele is a marble bas-relief stele of the Greek deity Persephone above a short punic inscription.