Related Research Articles

The Battle of Focchies was a significant naval engagement that took place on 12 May 1649, in the harbour of Focchies, Smyrna between a Venetian force of nineteen warships under the command of Giacomo da Riva, and an Ottoman force of eleven warships, ten galleasses, and seventy-two galleys, with the battle resulting in a crushing victory for the Venetian fleet. The battle was an episode in the Cretan War from 1645 to 1669 between the Venetian Republic and the Ottoman Empire over dominance of various territories in the Mediterranean Sea. The war was one in a series of wars between the two warring powers, which contested for control of the Adriatic and Mediterranean trade routes. The primary territory that was contested during the war was Crete, the largest and most profitable of the overseas holdings of the Venetian Republic. The battle came after a squadron of Venetian ships under the command of Giacomo da Riva, a Venetian admiral, came to the rescue of the blockading Venetian force in the Dardanelles Straits, after the blockade had run into unexpected weather conditions and many ships sunk as a result.

This battle took place on 26 May 1646 at the mouth of the Dardanelles Strait, during the Cretan War. The Ottoman fleet under the Kapudan Pasha, Kara Musa Pasha, tried to defeat the Venetian fleet, under Tommaso Morosini. The Venetians were blockading the Dardanelles, trying thus to prevent reinforcements and supplies to be brought to Crete, a Venetian possessions which the Ottomans had invaded the previous year, and to disrupt the flow of supplies to the Ottoman capital, Constantinople.

This battle took place on 21 June 1655 inside the mouth of the Dardanelles Strait. It was a clear victory for Venice over the Ottoman Empire during the Cretan War.

The Third Battle of the Dardanelles in the Fifth Ottoman-Venetian War took place on 26 and 27 June 1656 inside the Dardanelles Strait. The battle was a clear victory for Venice and the Knights Hospitaller over the Ottoman Empire, although their commander, Lorenzo Marcello, was killed on the first day.

The Fourth Battle of the Dardanelles in the Fifth Ottoman-Venetian War took place between 17 and 19 July 1657 outside the mouth of the Dardanelles Strait. The Ottomans succeeded in breaking the Venetian blockade over the Straits.

The Battle of Samothrace was an inconclusive battle which took place on 20 September 1698 near the island of Samothrace, during the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War. It was fought between Venice on one side, and the Ottoman Empire with its Tripolitanian and Tunisian vassals on the other. Venetian casualties were 299 killed and 622 wounded. Although it resulted in a stalemate, the Battle of Samothrace is notable as the last significant battle of the Great Turkish War.

The Battle of Andros took place on 22 August 1696 southeast of the Greek island of Andros between the fleets of the Republic of Venice and the Papal States under Bartolomeo Contarini on the one side and the Ottoman Navy, under Mezzo Morto Hüseyin Pasha, and allied Barbary forces on the other. The encounter was indecisive, and no vessels were lost on either side.

This battle, which took place on 16 May 1654, was the first of a series of tough battles just inside the mouth of the Dardanelles Strait, as Venice and sometimes the other Christian forces attempted to hold the Turks back from their invasion of Crete by attacking them early.

This battle was fought on 10 July 1651, with some minor fighting on 8 July, between the islands of Paros and Naxos in the Aegean Sea, between the Venetian and Ottoman fleets. It was a Venetian victory, but failed to achieve anything decisive.

The military history of the Republic of Venice started shortly after its founding, spanning a period from the 9th century until the Republic's fall in the 18th century.

Kurtoğlu Muslihiddin Reis was the admiral of the Ottoman Empire, as well as the Sanjak Bey of Rhodes. He played an important role in the Ottoman conquests of Egypt (1517) and Rhodes (1522) during which he commanded the Ottoman naval forces. He also helped establish the Ottoman Indian Ocean Fleet based in Suez, which was later commanded by his son, Kurtoğlu Hızır Reis.

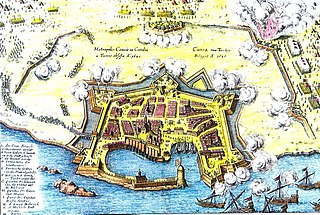

The Cretan War, also known as the War of Candia or the fifth Ottoman–Venetian war, was a conflict between the Republic of Venice and her allies against the Ottoman Empire and the Barbary States, because it was largely fought over the island of Crete, Venice's largest and richest overseas possession. The war lasted from 1645 to 1669 and was fought in Crete, especially in the city of Candia, and in numerous naval engagements and raids around the Aegean Sea, with Dalmatia providing a secondary theater of operations.

Lorenzo Marcello was a Venetian admiral.

The siege of Corfu took place on 8 July – 21 August 1716, when the Ottoman Empire besieged the city of Corfu, on the namesake island, then held by the Republic of Venice. The siege was part of the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War, and, coming in the aftermath of the lightning conquest of the Morea by the Ottoman forces in the previous year, was a major success for Venice, representing its last major military success and allowing it to preserve its rule over the Ionian Islands.

The Battle of Gallipoli occurred on 29 May 1416 between the fleets of the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire off the port city of Gallipoli, the main Ottoman naval base. The battle was the main episode of a brief conflict between the two powers, resulting from Ottoman attacks against possessions and shipping of the Venetians and their allies in the Aegean Sea in 1414–1415. The Venetian fleet, under Pietro Loredan, was charged with transporting a Venetian embassy to the Ottoman sultan, but was authorized to attack if the Ottomans refused to negotiate. The subsequent events are known chiefly from a detailed letter written by Loredan after the battle.

Alvise Loredan was a Venetian nobleman of the Loredan family. At a young age he became a galley captain, and served with distinction as a military commander, with a long record of battles against the Ottomans, from the naval expeditions to aid Thessalonica, to the Crusade of Varna, and the opening stages of the Ottoman–Venetian War of 1463–1479, as well as the Wars in Lombardy against the Duchy of Milan. He also served in a number of high government positions, as provincial governor, savio del consiglio, and Procuratore de Supra of Saint Mark's Basilica.

Vettore Cappello was a merchant, statesman and military commander of the Republic of Venice. After an early career as a merchant that gained him substantial wealth, he began his political career in 1439. His ascent to higher offices was rapid. He is chiefly remembered for his advocacy of a decisive policy against the Ottoman Empire, and his command of Venetian forces as Captain General of the Sea during the lead-up to and the first stages of the First Ottoman–Venetian War.

The siege of Chania happened during the initial stages of Cretan War (1645–1669). The Ottomans besieged the Venetian-held city of Chania, and after 56 days of siege, the Ottomans captured the city.

The siege of Chania in 1660 was an attempt by the Christian forces to recapture the city from the Ottoman hold. The Ottoman managed to thwart the Christian attempt to capture the city.

The siege of Rethymno happened during the Cretan War when the Ottomans launched a campaign to conquer the city of Rethymno in Crete from the Venetians. The Ottomans captured the city in the end.

References

- ↑ Setton 1991, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Setton 1991, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ Anderson 1952, p. 125.

- ↑ Setton 1991, p. 139.

- ↑ Setton 1991, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Anderson 1952, pp. 126–127.

- ↑ Setton 1991, p. 140.

- ↑ Anderson 1952, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 Setton 1991, p. 141.

- 1 2 3 4 Anderson 1952, p. 128.

- ↑ Anderson 1952, pp. 128–129.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Anderson 1952, p. 129.

- ↑ Anderson 1952, pp. 129–130.

- 1 2 Anderson 1952, p. 130.