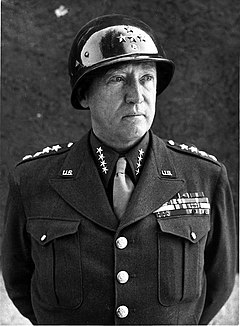

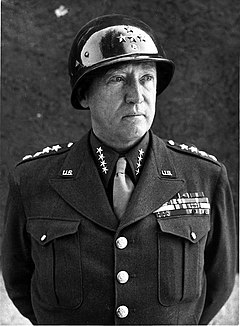

George Smith Patton Jr. was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh United States Army in the Mediterranean theater of World War II, and the Third United States Army in France and Germany after the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944.

The Battle of Kasserine Pass was a series of battles of the Tunisia Campaign of World War II that took place in February 1943 at Kasserine Pass, a 2-mile-wide (3.2 km) gap in the Grand Dorsal chain of the Atlas Mountains in west central Tunisia.

The 21st Army Group was a World War II British headquarters formation, in command of two field armies and other supporting units, consisting primarily of the British Second Army and the First Canadian Army. Established in London during July 1943, under the command of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), it was assigned to Operation Overlord, the Western Allied invasion of Europe, and was an important Allied force in the European Theatre. At various times during its existence, the 21st Army Group had additional British, Canadian, American and Polish field armies or corps attached to it. The 21st Army Group operated in Northern France, Luxembourg, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany from June 1944 until August 1945, when it was renamed the British Army of the Rhine (BAOR).

The 6th United States Army Group was an Allied Army Group that fought in the European Theater of Operations during World War II. Made up of field armies from both the United States Army and the French Army, it fought in France, Germany, Austria, and, briefly, Italy. Also referred to as the Southern Group of Armies, it was established in July 1944 and commanded throughout its duration by General Jacob L. Devers.

Operation Cobra was the codename for an offensive launched by the United States First Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the distraction of the Germans by the British and Canadian attacks around Caen in Operation Goodwood, and thereby break through the German defenses that were penning in their forces while the Germans were unbalanced. Once a corridor had been created, the First Army would then be able to advance into Brittany, rolling up the German flanks once free of the constraints of the bocage country. After a slow start, the offensive gathered momentum and German resistance collapsed as scattered remnants of broken units fought to escape to the Seine. Lacking the resources to cope with the situation, the German response was ineffectual and the entire Normandy front soon collapsed. Operation Cobra, together with concurrent offensives by the British Second Army and the Canadian First Army, was decisive in securing an Allied victory in the Normandy campaign.

The Falaise pocket or battle of the Falaise pocket was the decisive engagement of the Battle of Normandy in the Second World War. A pocket was formed around Falaise, Calvados, in which the German Army Group B, with the 7th Army and the Fifth Panzer Army were encircled by the Western Allies. It is also referred to as the battle of the Falaise gap. The battle resulted in the destruction of most of Army Group B west of the Seine, which opened the way to Paris and the Franco-German border for the Allied armies on the Western Front.

Operation Lüttich was a codename given to a German counter-attack during the Battle of Normandy, which took place around the American positions near Mortain in northwestern France from 7 August to 13 August 1944. The offensive is also referred to in American and British histories of the Battle of Normandy as the Mortain counterattack.

The Allied advance from Paris to the Rhine, also known as the Siegfried Line campaign, was a phase in the Western European campaign of World War II.

The 9th Panzer Division was a panzer division of the Wehrmacht Army during World War II. It came into existence after 4th Light Division was reorganized in January 1940. The division was headquartered in Vienna, in the German military district Wehrkreis XVII.

The Colmar Pocket was the area held in central Alsace, France, by the German Nineteenth Army from November 1944 to February 1945, against the U.S. 6th Army Group during World War II. It was formed when 6th AG liberated southern and northern Alsace and adjacent eastern Lorraine, but could not clear central Alsace. During Operation Nordwind in December 1944, the 19th Army attacked north out of the Pocket in support of other German forces attacking south from the Saar into northern Alsace. In late January and early February 1945, the French First Army cleared the Pocket of German forces.

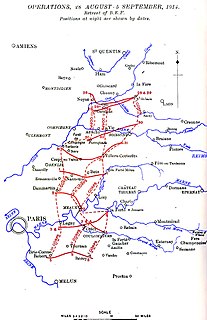

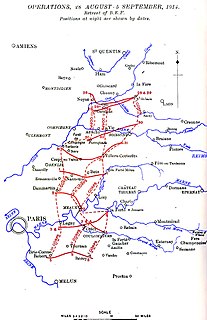

The Great Retreat, also known as the retreat from Mons, was the long withdrawal to the River Marne in August and September 1914 by the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) and the French Fifth Army, Allied forces on the Western Front in the First World War, after their defeat by the armies of the German Empire at the Battle of Charleroi and the Battle of Mons. A counteroffensive by the Fifth Army, with some assistance from the BEF, at the First Battle of Guise failed to end the German advance, and the retreat continued to and beyond the Marne. From 5 to 12 September, the First Battle of the Marne ended the Allied retreat and forced the German armies to retire towards the Aisne River and to fight the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September). Reciprocal attempts to outflank the opposing armies to the north known as the Race to the Sea followed (17 September – 17 October).

"Rhino tank" was the American nickname for Allied tanks fitted with "tusks", or bocage cutting devices, during World War II. The British designation for the modifications was Prongs.

The Western Allied invasion of Germany was coordinated by the Western Allies during the final months of hostilities in the European theatre of World War II. In preparation for the Allied invasion of Germany east of the Rhine, a series of offensive operations were designed to seize and capture the east and west bank of the Rhine: Operation Veritable and Operation Grenade in February 1945, and Operation Lumberjack and Operation Undertone in March 1945. The Allied invasion of Germany east of the Rhine started with the Western Allies crossing the river on 22 March 1945 before fanning out and overrunning all of western Germany from the Baltic in the north to the Alpine passes in the south, where they linked up with troops of the U.S. Fifth Army in Italy. Combined with the capture of Berchtesgaden, any hope of Nazi leadership continuing to wage war from a so-called "National redoubt" or escape through the Alps was crushed, shortly followed by unconditional German surrender on 8 May 1945. This is known as the Central Europe Campaign in United States military histories.

The 1st Army Corps was first formed before World War I. During World War II it fought in the Campaign for France in 1940, on the Mediterranean islands of Corsica and Elba in 1943 - 1944, and in the campaigns to liberate France in 1944 and invade Germany in 1945.

The 116th Panzer Division, also known as the "Windhund (Greyhound) Division", was a German armoured formation that saw combat during World War II.

The 712th Infantry Division was a German Army infantry division in World War II.

The 746th Tank Battalion was an independent tank battalion that participated in the European Theater of Operations with the United States Army in World War II. It was one of five tank battalions which landed in Normandy on D-Day. The battalion participated in combat operations throughout northern Europe until V-E Day. It served primarily as an attachment to the 9th Infantry Division, but fought alongside numerous other units as well. It was inactivated in October 1945.

General George Patton's Third Army's Seine River Crossing at Mantes-Gassicourt was the first allied bridgehead across the Seine River in the aftermath of Operation Overlord, which allowed the Allies to engage in the Liberation of Paris. During the two days of the bridge crossing, American anti-aircraft artillery shot down almost fifty German planes.

The XIX Army Corps was an armored corps of the German Wehrmacht between 1 July 1939 and 16 November 1940, when the unit was renamed Panzer Group 2 and later 2nd Panzer Army. It took part in the Invasion of Poland and the Battle of France.

The Battle of Saint-Malo was fought between Allied and German forces to control the French coastal town of Saint-Malo during World War II. The battle formed part of the Allied breakout across France and took place between 4 August and 2 September 1944. United States Army units, with the support of Free French and British forces, successfully assaulted the town and defeated its German defenders. Much of Saint-Malo was destroyed in the fighting. The German garrison on a nearby island continued to resist until 2 September.