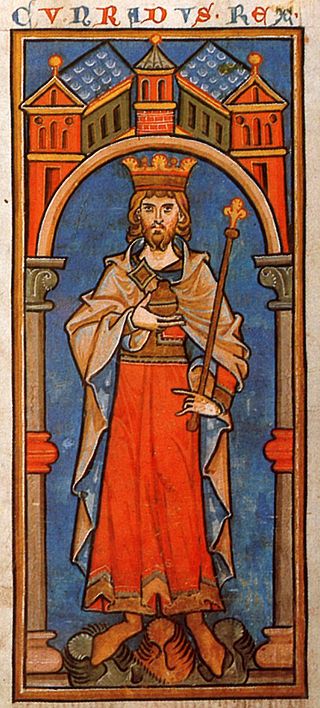

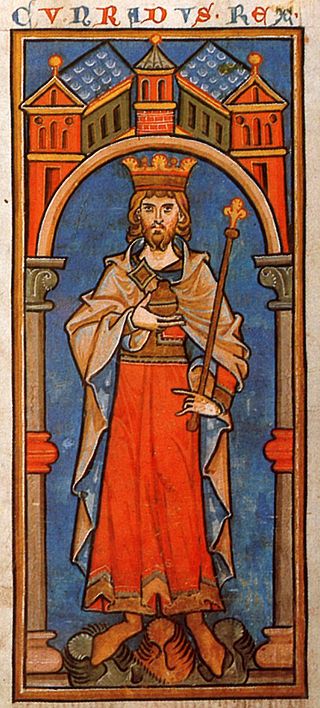

Conrad III of the Hohenstaufen dynasty was from 1116 to 1120 Duke of Franconia, from 1127 to 1135 anti-king of his predecessor Lothair III, and from 1138 until his death in 1152 King of the Romans in the Holy Roman Empire. He was the son of Duke Frederick I of Swabia and Agnes, a daughter of the Salian Emperor Henry IV.

Henry IX, was a member of the House of Welf, a powerful dynasty in medieval Germany. He was born around 1075 and died in 1126. Henry IX is often referred to as “Henry the Black” and ruled as Duke of Bavaria from 1120 until his death in 1126.

Otto II, called the Illustrious, was the Duke of Bavaria from 1231 and Count Palatine of the Rhine from 1214. He was the son of Louis I and Ludmilla of Bohemia and a member of the Wittelsbach dynasty.

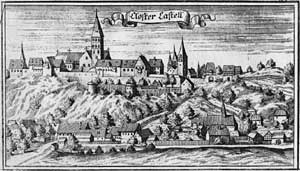

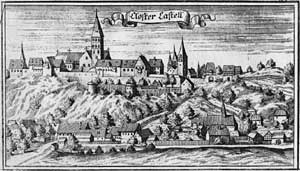

Kastl Abbey is a former Benedictine monastery in Kastl in the Upper Palatinate, Bavaria.

Henry Berengar (1136/7–1150), sometimes numbered Henry (VI), was the eldest legitimate son of Conrad III of Germany and his second wife, Gertrude von Sulzbach. He was named after his father's maternal grandfather, the Emperor Henry IV, and his mother's father, Count Berengar II of Sulzbach. He was groomed for the succession, but predeceased his father.

Berchtesgaden Provostry or the Prince-Provostry of Berchtesgaden was an immediate principality of the Holy Roman Empire, held by a canonry led by a Prince-Provost.

Gertrude of Sulzbach was German queen from 1138 until her death as the second wife of the Hohenstaufen king Conrad III.

Matilda of Sulzbach was Margravine of Istria by marriage to Engelbert III of Istria. Different dates of death are given in the necrologies of Baumburg Abbey and two monasteries of Salzburg.

Adelheid of Wolfratshausen was a countess of Sulzbach as the second wife of Berengar II, Count of Sulzbach. Slightly different dates for her death are given in the necrologies of Tegernsee and the Salzburg Cathedral.

Henry V was King of Germany and Holy Roman Emperor, as the fourth and last ruler of the Salian dynasty. He was made co-ruler by his father, Henry IV, in 1098.

Conrad I [of Abenberg] was Archbishop of Salzburg, Austria, in the first half of the 12th century.

Höglwörth Abbey is a former monastery of the Augustinian Canons in Höglwörth, near Anger in Bavaria, in the Archdiocese of Munich and Freising.

Baumburg Abbey is a former monastery of Augustinian Canons Regular in the northern Traunstein district of Bavaria, Germany. It was founded in 1107–1109 and dissolved in 1803. Today Baumburg is a Catholic deanery that covers the parishes of the northern Chiemgau.

Immilla was a duchess consort of Swabia by marriage to Otto III, Duke of Swabia, and a margravine of Meissen by marriage to Ekbert I of Meissen. She was regent of Meissen during the minority of her son, Ekbert II.

Count Gebhard III of Sulzbach came from the noble Counts of Sulzbach and was a son of Count Berengar II of Sulzbach and his second wife, Adelheid of Dießen-Wolfratshausen.

Arnold I, Count of Loon (Looz) from about 1079, son of Emmo, Count of Loon, and Suanhildis, daughter of Dirk III, Count of Holland, and his wife Othelandis.

Harburg Castle in Harburg, Bavaria, in the Donau-Ries district, is an extensive mediaeval complex from the 11th / 12th century. Originally it was a Staufer castle and was owned by the princely House of Oettingen-Wallerstein. Since 2000 the castle belongs to the Prince of Oettingen-Wallerstein Cultural Foundation, which has the mission to preserve this unique castle for the present and future.

The Heuberg Castle is located on the Salzach River in the hamlet of St. Georgen in the municipality of Bruck an der Großglocknerstraße in Salzburg, Austria.